The story of OSX.Pirrit continues. In this installment, we reveal who’s behind this particularly nasty piece of adware that targets Mac OS X.

To review, I first encountered this Windows adware port back in April 2016. After dissecting it, I discovered that this wasn’t your typical adware program that just floods a person’s browser with ads. With components such as persistence and the ability to obtain root access, OSX.Pirrit has characteristics usually seen in malware.

The catch: OSX.Pirrit didn’t execute any harmful functions but the potential to carry out these much more malicious activities was there. Attackers could have used the capabilities built into OSX.Pirrit to install a keylogger and steal your log-in credentials or make off with your company’s intellectual property, among many other bad outcomes. The greater point I’m trying to make is that even Macs are vulnerable to threats.

Fast forward to two weeks ago when I was informed by one of my Twitter followers that the removal script I had created for OSX.Pirrit no longer worked because the program had mutated. I was surprised to learn that there was a new variant and that it still works even though some of Pirrit’s servers and a few distribution websites had been taken down after my earlier research was published.

The person who contacted me about the removal script was kind enough to share some files that new variant had dropped on his machine. That means that we have all of the “evil” files (the ad-injecting-traffic-hijacking proxy, configuration files) but without the dropper itself.

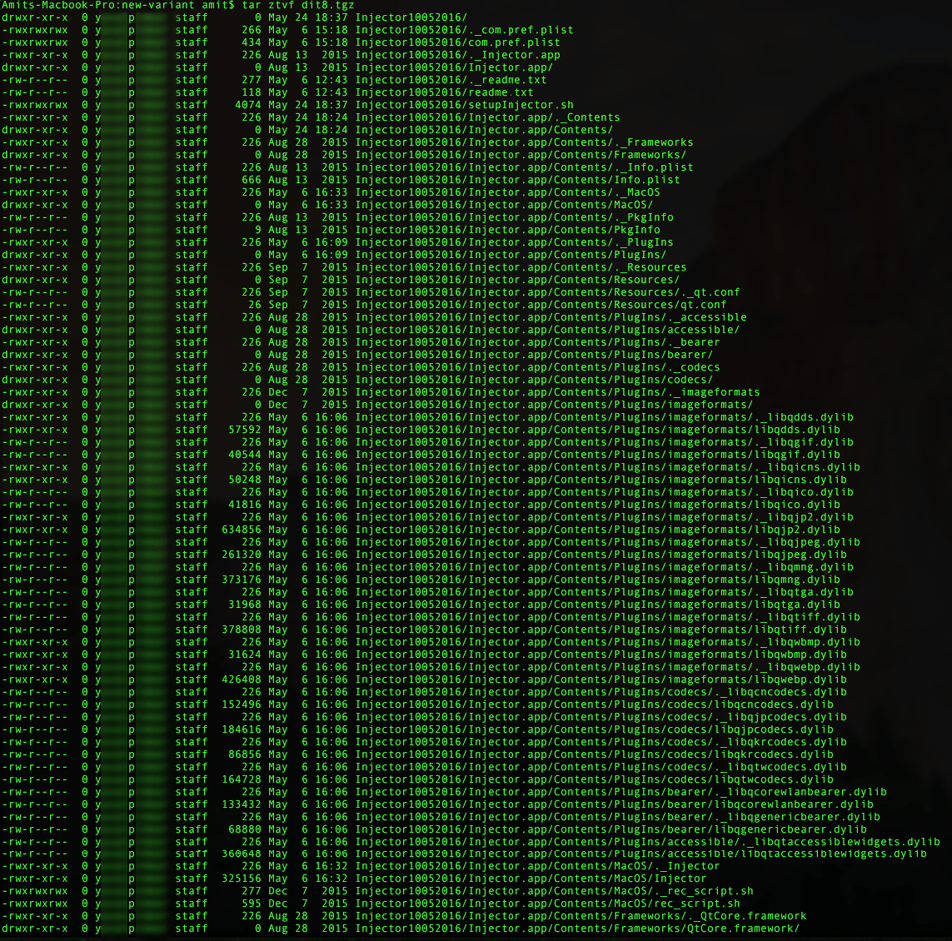

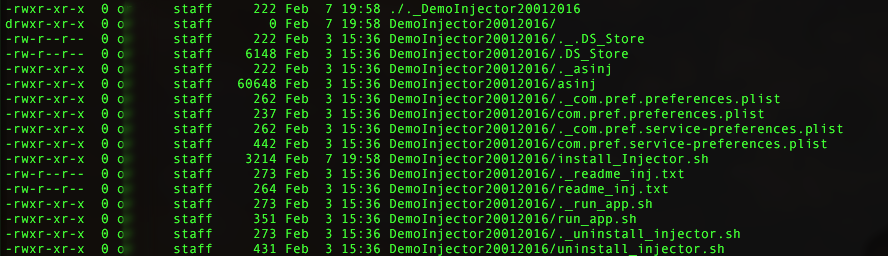

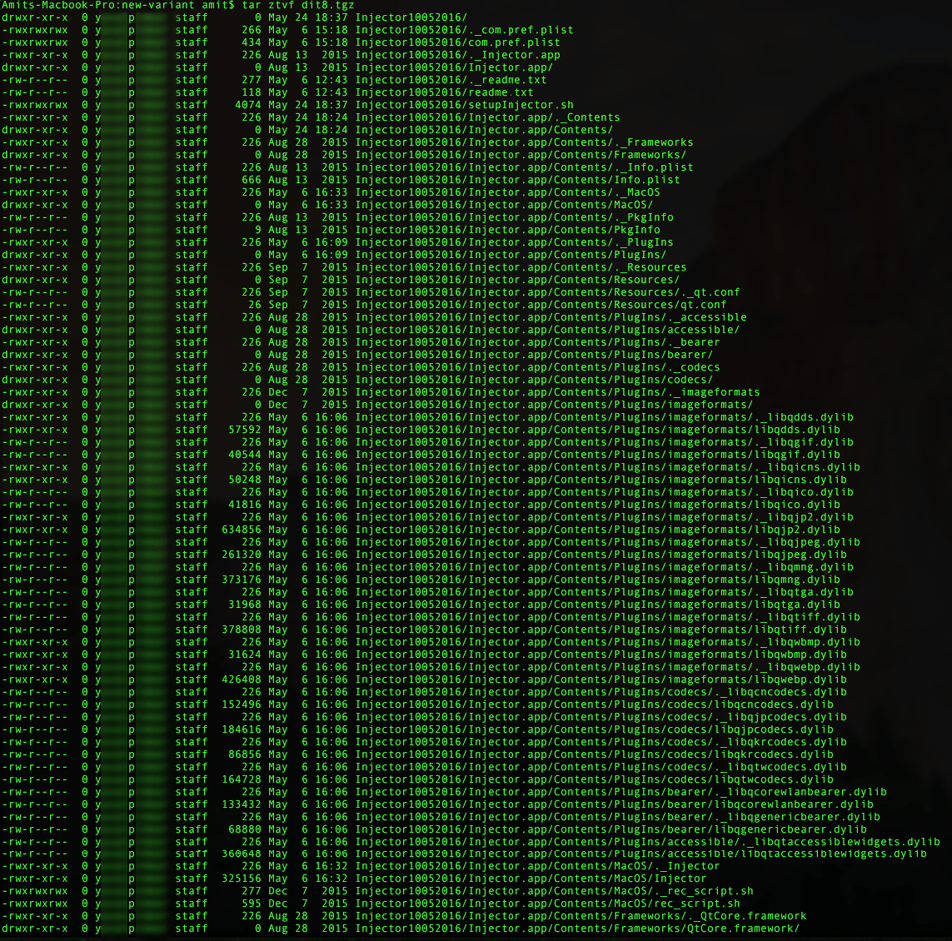

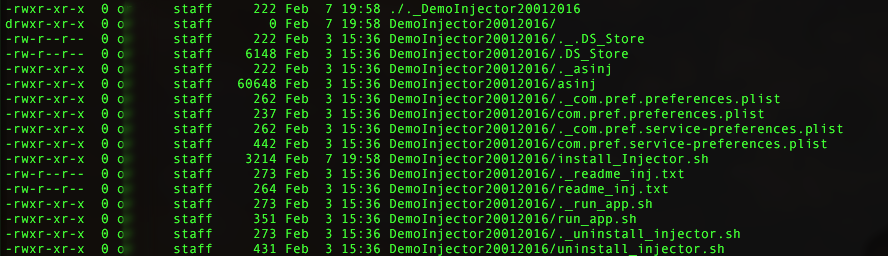

Among the dropped files was an archive file called dit8.tgz. I discussed it in my previous research report on OSX.Pirrit as well as during my presentation at the LayerOne conference. Dit8.tgz contained the ad-injecting-traffic-hijacking proxy server that’s being installed on the victim’s machine. Unpacking the file to see what was inside the archive would have triggered my antivirus program since it would have identified the file as OSX.Pirrit. Since I didn’t want to disable my antivirus programs, I decided to list the files inside of the tgz archive.

Until this point, every other lead I followed lead to a dead end. The domains were registered as private and there was nothing that linked this adware to a person or company. Whoever created the variant did their best to avoid leaving evidence that could be traced back to them and lead to their getting caught.

However, the variant’s creators made a crucial mistake that caused their entire operation to topple like a house of cards. The tar.gz archive format is a Posix format, which means that it also saves all of the file attributes (like owners and permissions) inside of the archive as they were on the computer that the archive was created on. So when I listed the files inside the archive, I could see the user name of the person who created the archive.

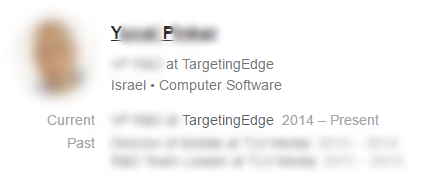

The people who created this archive weren't too careful. The user name was a person’s first and last name, so, naturally, I plugged that name into Google and learned that the person is an executive at TargetingEdge, an Israeli company that bills itself as an “online marketing” company. TargetingEdge’s website just says it’s “coming soon to a browser near you” and doesn’t give any information about the company.

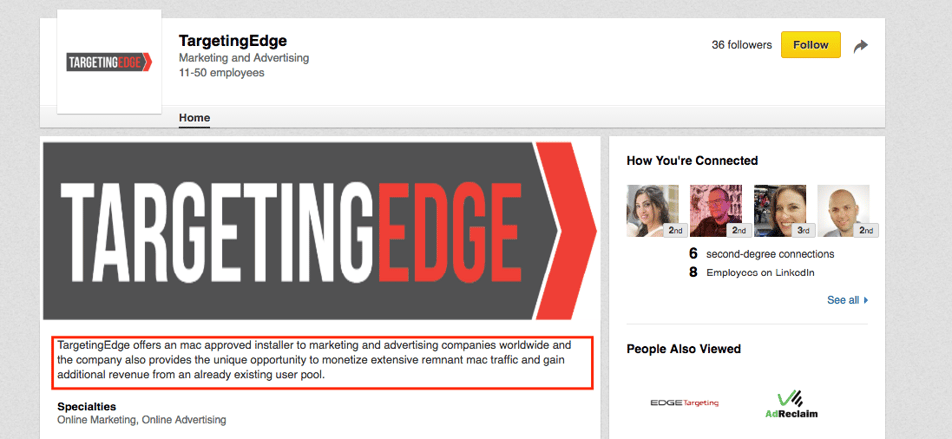

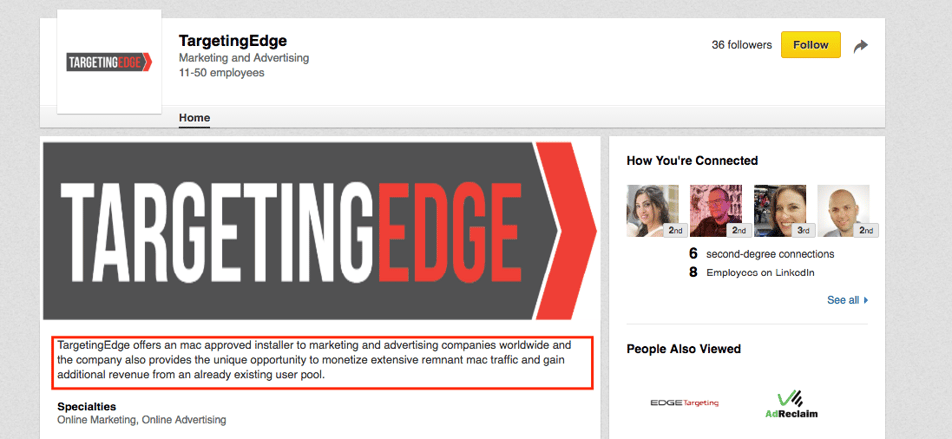

TargetingEdge’s LinkedIn profile doesn’t offer much more information on what exactly the company does, but from what scant details are provided, it sounds like they make very aggressive adware. TargetingEdge “offers an mac-approved installer” and “provides the unique opportunity to monetize extensive remnant mac traffic and gain additional revenue from an already existing user pool,” according to LinkedIn. This perfectly describes how OSX.Pirrit functions.

The installer TargetingEdge describes on its LinkedIn page works exactly like OSX.Pirrit.

The archive of the OSX.Pirrit variant included the first and last name of the person who created the program. The name has been concealed.

The LinkedIn profile of the mastermind behind OSX.Pirrit.

TargetingEdge is related to two other companies, TLV Media, which makes an ad targeting and ad monetization platform, and Feature Forward, which sells a video platform. According to LinkedIn, all three companies have the same board of directors and the executive who created the OSX.Pirrit variant previously worked for TLV Media.

Unlike the older version of OSX.Pirrit, the new variant includes a component that checks for competing programs on a computer, removes any competitors that are discovered and rewrites autoruns when removed. The new version also has new 14 hidden users and no longer includes the Windows binary found in the original version. I assume they read my earlier research on OSX.Pirrit and made the changes. Given that they didn’t clean up the archive, they must have been in a rush to update the adware.

Once I figured out the company behind OSX.Pirrit, I then decided to try to find out which individual created it. I discovered the older version was packed by a guy who was much more careful and only used his first name. Since I knew the company he most likely worked for and his first name, I used this information to easily find his LinkedIn profile. He is a Web developer at TargetingEdge.

Figuring out who created OSX.Pirrit didn’t require the detective skills of Nancy Drew or the Hardy Boys. I didn’t have to make a wild guess that the names in the archive belonged to the people who created OSX.Pirrit and its variant. Confirming this hypothesis merely required some basic Google and LinkedIn searches.

The archive of the older version of OSX.Pirrit included the first name of the person who created it. The name has been concealed.

Always download open-source software and freeware from a vendor's website and not from a third party. Not every package installer can be trusted. Attackers often take freeware or open-source programs, remove the installer that comes with the software and replace it with an installer that loads adware onto a machine.

This is how OSX.Pirrit spread. It piggybacked on legitimate software. The adware’s creators removed the original installers for MPlayerX, NicePlayer and VLC, legitimate media players that people can easily download, and replaced them with an installer that has OSX.Pirrit as well as the media player.

Next, the applications were uploaded to download sites that contain several programs that appear authentic but are, in fact, malicious. These download sites attract droves of people, giving companies like TargetingEdge an incentive to offer their dodgy software on the site. Often times the company that developed the malicious installer that carries the software and the adware will pay the download site to offer it. People are duped into believing that they downloaded a genuine application. Instead, they get adware.

Not everyone is a security researcher. Most people search Google for a certain program and download it from the first website that appears in the search results. They don’t consider that some of these sites are totally fraudulent.

Of course, TargetingEdge can say that while they made the installer, they didn’t provide it to the download sites and can’t control its use. While this maybe true, TargetingEdge could have included features that allow users to fully understand how the software works or better control how it operates.

For instance, there’s no end user license agreement that spells out in clear language how the program functions. Additionally, TargetingEdge could have made OSX.Pirrit’s uninstall instructions easier to access. In both the original program and its variant, the uninstall instructions were buried in either the temp directories or in the hidden user's home directory, making them difficult for the typical user to find and essentially useless.

When Windows users downloaded software installers containing Pirrit, they were given the option to opt out of installing other programs that are billed as “special offers.” They’re really more adware, but at least users are given the chance to decide not to download them. This opt out option isn’t included in the Mac variant of Pirrit.

Another point worth mentioning is to not underestimate the dangers posed by adware. Most security professionals dismiss adware and consider these programs low security risks compared to the other issues they face. Attackers, though, realize that security teams dismiss adware and are including components in these threats that make them more akin to malware. Potentially unwanted programs don’t exist. If there’s any doubt about an application’s function or why it’s on a user’s machine, it should be removed. Or if this approach is unfeasible given the size of an organization and the number of machines infected with commodity threats like adware, companies need a way to monitor these programs and detect when they display atypical behavior.

OSX.Pirrit allows attackers to take full control of a computer. Instead of flooding a person’s browser with ads, attackers could have installed a keylogger to capture log-in information to your bank account or made off with your company’s intellectual property. Companies need to know what’s happening on their machines, including Macs, because the instant an enterprise doesn’t, they’re compromised.

The archive of the older version of OSX.Pirrit included the first name of the person who created it. The name has been concealed.

The archive of the older version of OSX.Pirrit included the first name of the person who created it. The name has been concealed.