Research by: Amit Serper

Introduction

Cybereason Nocturnus is investigating a campaign where attackers are trojanizing multiple hacking tools with njRat, a well known RAT. The campaign ultimately gives attackers total access to the target machine. The threat actors behind this campaign are posting malware embedded inside various hacking tools and cracks for those tools on several websites. Once the files are downloaded and opened, the attackers are able to completely take over the victim’s machine. In this write-up we present our analysis of the TTPs of the attackers and the indicators of compromise. In the investigation of this campaign, we have found hundreds of trojanized files and a lot of information about the threat actors infrastructure.

Learn more about what trends we expect to see this year in our 2020 security predictions report.

Key Points

- Widespread Campaign: We have found a widespread hacking campaign that uses the njRat trojan to hijack the victim’s machine, giving the threat actors complete access that can be used for anything from conducting DDoS attacks to stealing sensitive data.

- Baiting Hackers: The malware is spreading by turning various hacking tools and other installers into trojans. The threat actors are posting the maliciously modified files on various forums and websites to bait other hackers.

- Using Vulnerable WordPress Websites: The threat actors are hacking vulnerable WordPress installations to host their malicious njRat payloads.

- A “Malware Factory”: It seems as if the threat actors behind this campaign are building new iterations of their hacking tools on a daily basis.

-

table of contents

Malware analysis

While reviewing some detection data last week, we stumbled on a new detection of njRat in one of the environments we are monitoring. njRat is popular in the Middle East and gives its operators the ability to hijack the victim’s machine for keylogging, taking screenshots, file manipulation and exfiltration, webcam and microphone recording.

While njRat is a fairly prevalent threat and popular RAT, this particular infection caught our eye.

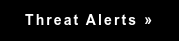

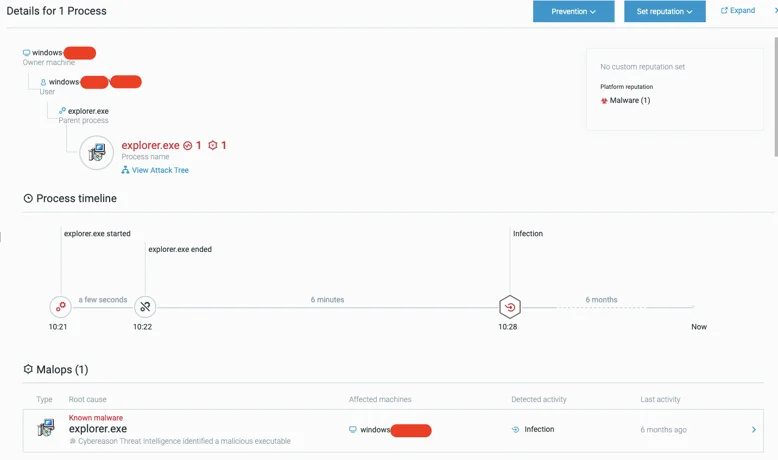

Initial detection of the njRat in the Cybereason Defense Platform.

The process appears to be masquerading as a legitimate Windows application (explorer.exe). However, when checking its hash on VirusTotal, the sample seems to be very new, just a few hours old at the time. In the affected environment, it looks as if the njRat is contacting two IP addresses: one of them was unknown to us at the time (capeturk.com - more on that later) and the other, (anandpen.com) a compromised website of an Indian office supplies manufacturer.

|

Hostname

|

IP

|

|

capeturk.com

|

104.206.239.81

|

|

www.anandpen.com

|

209.99.16.94

|

IP addresses and hostnames contacted by the malware.

anandpen.com is a hacked WordPress website that serves malware from one of its internal WordPress directories. This is a common practice by attackers who are exploiting vulnerable WordPress installations. In this case, one of the payloads was served through the /wp-includes/images/media/1/explorer.zip path on the anandpen.com domain.

After running a few YARA queries and searching for all of the samples on VT associated with the two aforementioned IP addresses, we found dozens of different samples of the same njRat hosted on the same server. Each sample had a different creation time, but they were all hosted on the same server and actively targeting victims.

As mentioned before, all of the observed samples (including the detection on one of the environments we are monitoring) had the name of a legitimate Windows process, like svchost.exe or explorer.exe, yet all of them were executed from subdirectories inside %AppData%. Clearly, some mischief was taking place, but the root cause for these executions was unknown since the files were dropped in the environment prior to the deployment of our product.

Finding the Root Cause

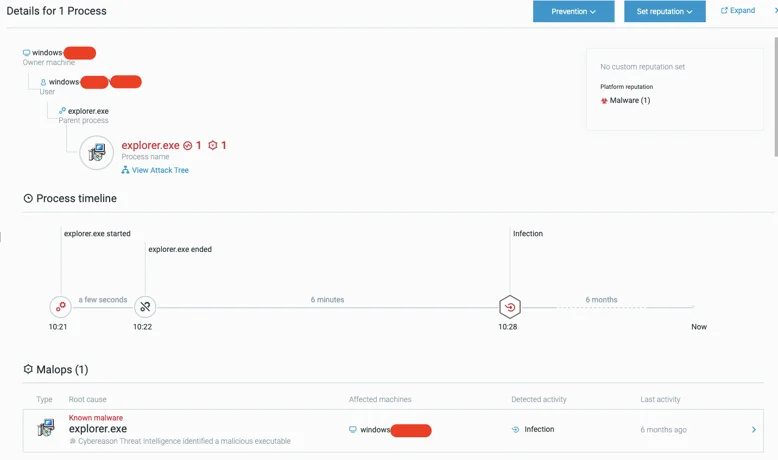

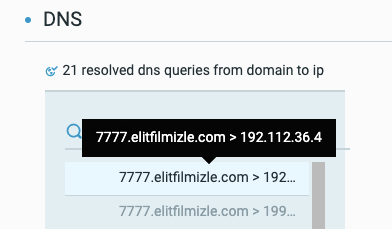

When investigating the Malop, it’s clear the malicious explorer.exe process is communicating with the hostname 7777.elitfilmizle[.]com.

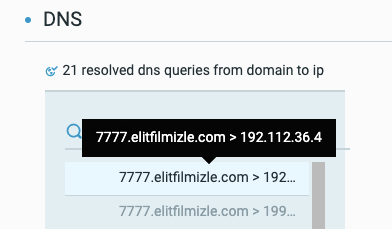

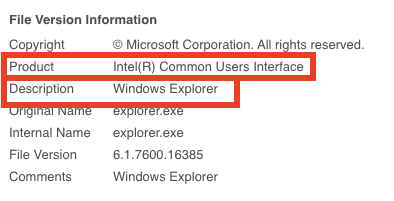

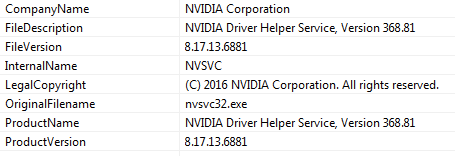

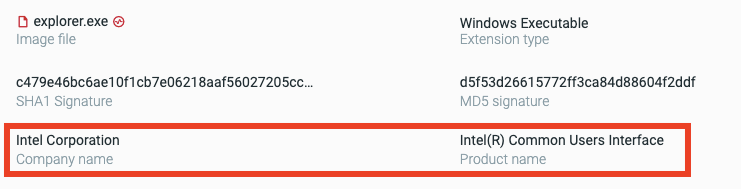

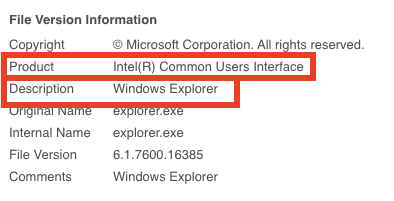

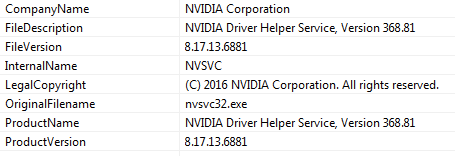

The information fields in the unsigned PE file have an interesting peculiarity to them:

Highlighted are the company name and product name of the file, as seen in the Cybereason Defense Platform.

Further inspection of the file version information reveals more mismatches:

Additional information about file hash d5f53d26615772ff3ca84d88604f2ddf.

Additional information about file hash d5f53d26615772ff3ca84d88604f2ddf.

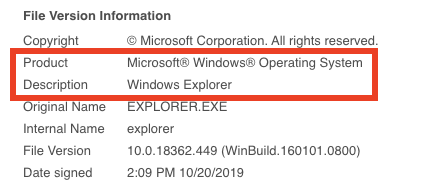

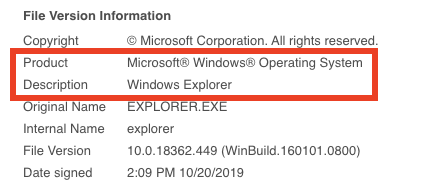

For comparison, here’s the product information field for a legitimate signed explorer.exe from a Windows 10 Pro build 1903:

Legitimate explorer.exe hash: 4E196CEA0C9C46A7D656C67E52E8C7C7.

While the file name is explorer.exe, the company name is “Intel Corporation” and the product name is “Intel(R) Common Users Interface”, which certainly doesn’t make much sense.

Some more hints (notice the date) are in the PDB path for said file:

There are a few interesting details in this PDB path:

- “03-02-2020” - this date implies there are multiple different variants of the same project (past/future versions.Upon further investigation, I found many of these variants.

- “TripleDES-Rijn-GZIPP” - this refers to methods the loader of the malware uses to masquerade it’s true purpose (more on that later)

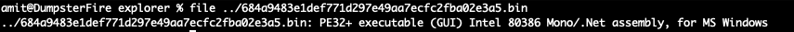

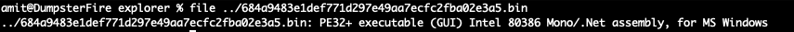

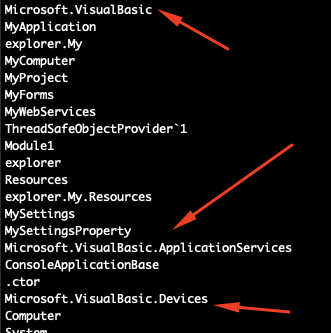

When examining explorer.exe, it’s clear that it is actually a .NET PE executable:

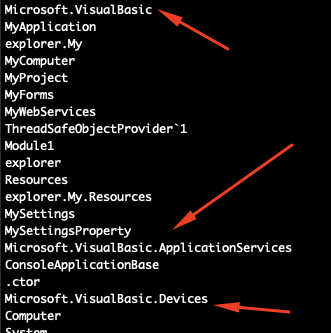

Upon closer inspection, this file was originally written in Visual Basic, which is typical for njRat loaders:

Some of the crypter functionality is available once the executable is decompiled (note that the decomplication is to C# for legibility):

The three red arrows in the screenshot are directly related to the string I mentioned before, which appeared in the PDB (“TripleDES-Rijn-GZIPP”). The arrows point to the method of encryption and compression (one can say obfuscation) of the file: TripleDES followed by AES (Rijndael) and then GZIP compression. The blue arrows point to the key used for both the TripleDES and AES encryption, which is “abc123456”.

Once the loader unpacks the payload, it deletes the original loader file and continues to run its course. The malware will create a new directory, %USER%\AppData\Roaming\Intel Corporation\Intel(R) Common User Interface\8.1.1.7800\ and use it as a staging directory. The njRat loader continues to drop files into that staging directory, eventually dropping the main njRat payload with a random name. The malware changes the random file name to explorer.exe, copies it to %AppData%\roaming, and executes it from there. After it executes, the fake explorer.exe (the njRat payload) runs a netsh command to communicate to the outside world. It alters the Windows Firewall with the following command:

|

netsh firewall add allowedprogram 'C:\Users\user\AppData\Roaming\explorer.exe' 'explorer.exe'

|

njRat contacts several servers to receive commands and files from its operators:

- Capeturk.com - a repository for a newer version of njRat used in this campaign

- Blog.capeturk.com - the C2 for njRat

- Anandpen.com - the repository for various njRat versions and other tools used by the attackers

-

Note: anandpen.com was hacked by the attackers. It is a WordPress-powered website of a pen manufacturing company from India. We have reached out to the company and informed them about the incident, but we have yet to receive a response.

Threat Intel

Now that we understand how this njRat campaign operates and which servers it’s connecting to, there is one question that remains: how do people get infected?

After examining the environment, it’s clear there were many hacking and penetration tools deployed in various paths on the target machine. By examining the hashes on the network, we could see that all of the hacking tools had various cracks deployed alongside them. Both the tools and the cracks were all infected with this njRat campaign.

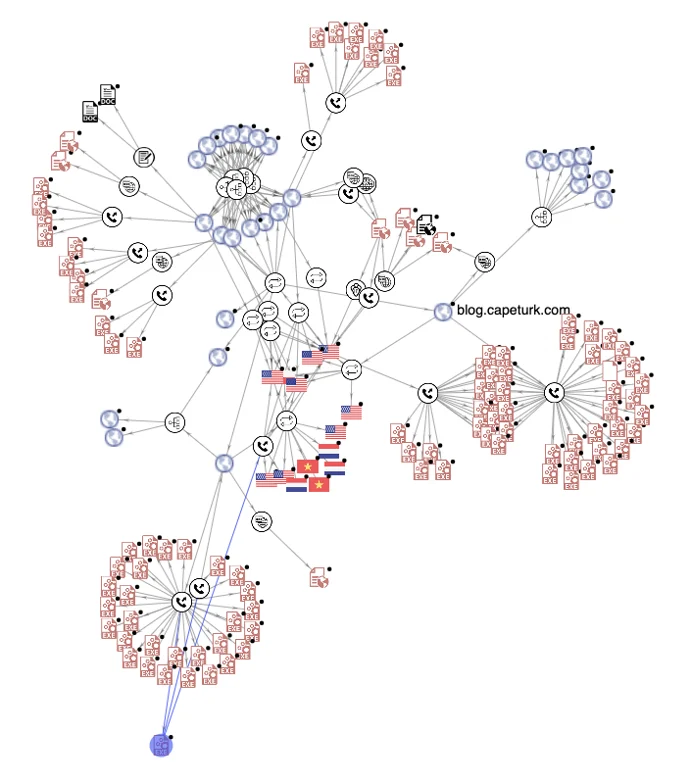

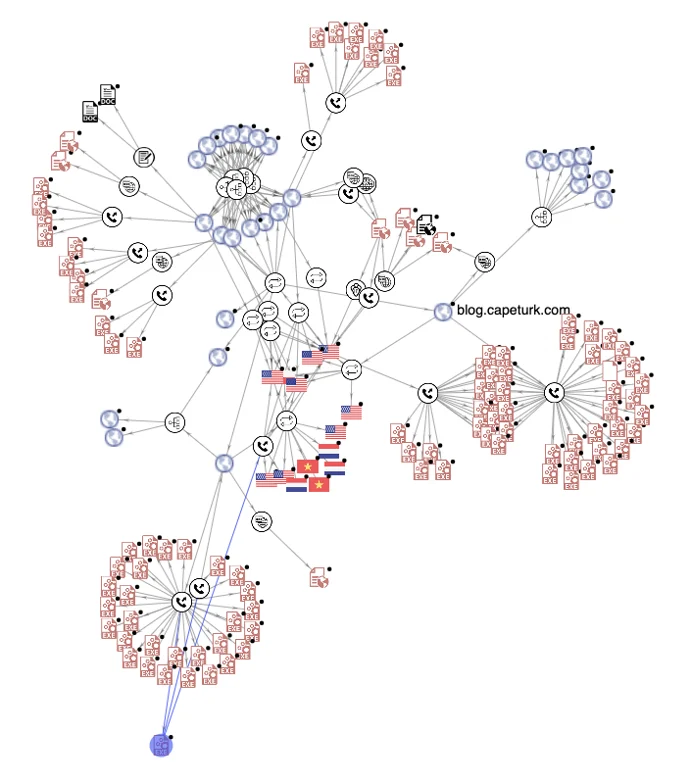

By correlating the identified servers with the hashes found on VT using VTGraph, we can see there are plenty of samples related to this campaign:

VTGraph correlating between samples and servers.

VTGraph correlating between samples and servers.

At this point, we know there is a campaign targeting hackers by trojanizing various hacking tools. The one question that remains is, “where are all of these trojanized tools coming from?”

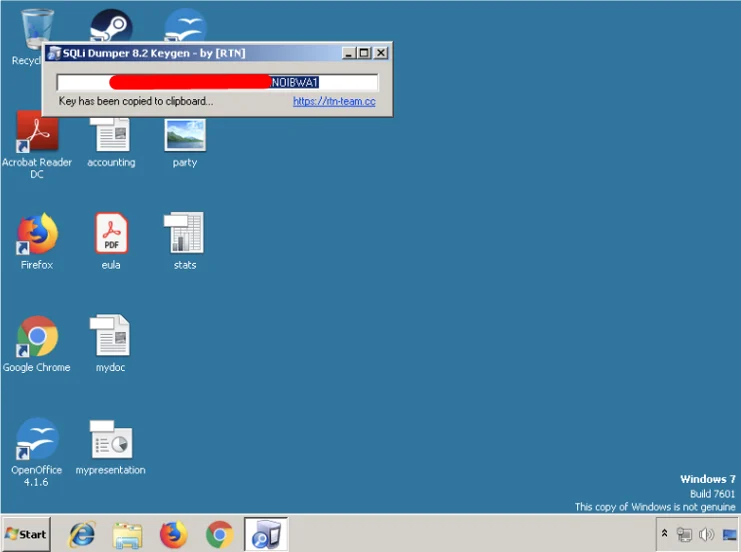

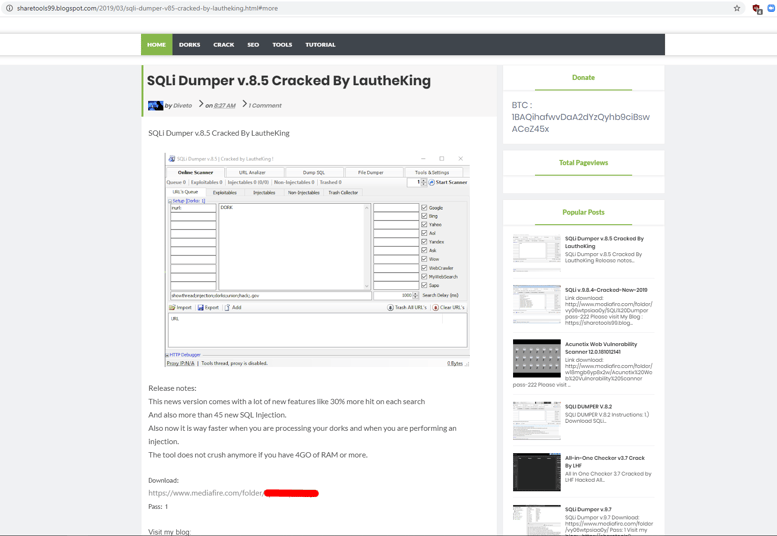

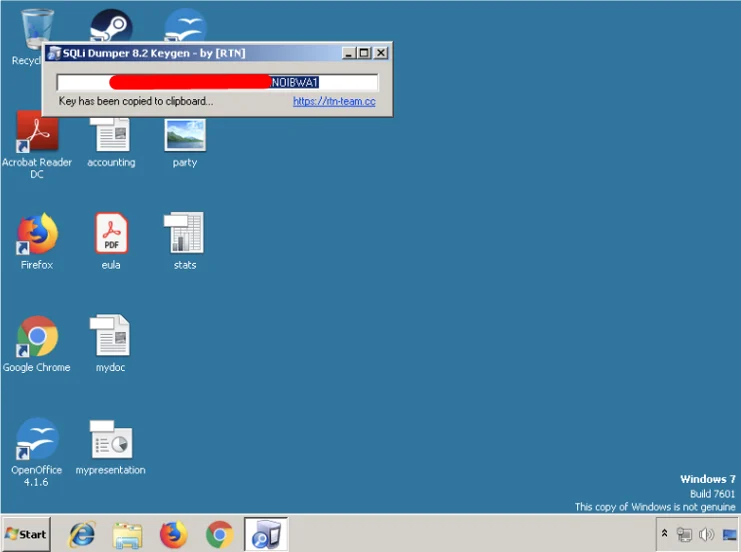

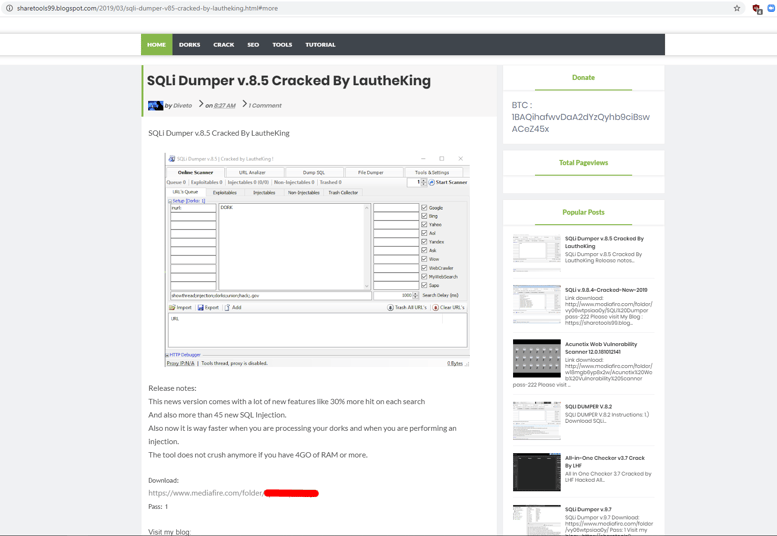

One of the files on the system was a keygen for an SQLi Dumper. SQLi Dumper is a tool used to perform all kinds of SQL injections and data dumps.

One of the infected keygens for the program SQLi dumper v8.2.

As we can see in the screenshot below, the keygen is credited to [RTN]. RTN is a group that writes cracks to various programs. They have a website and a forum:

Screenshot from RTN’s website.

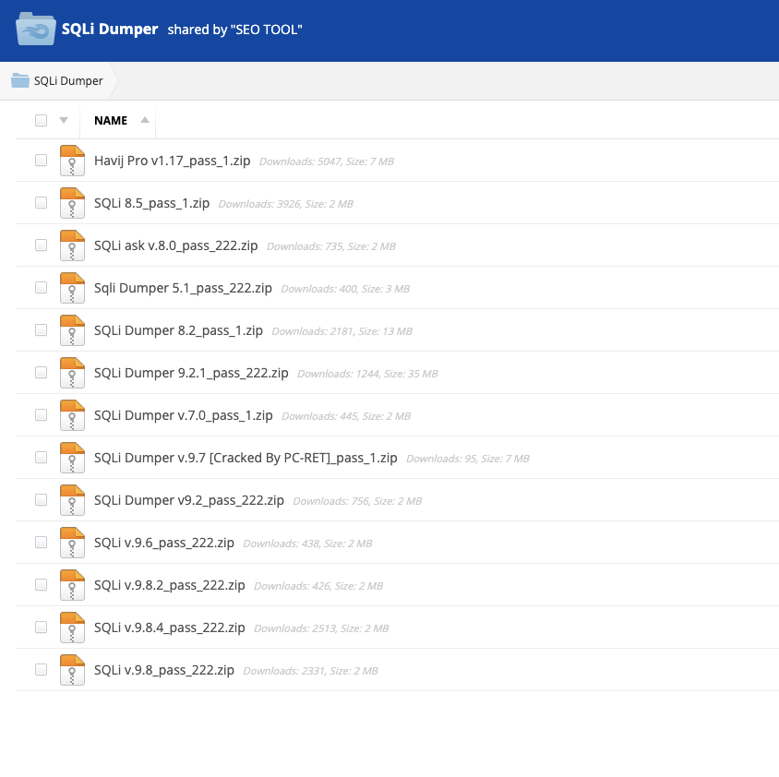

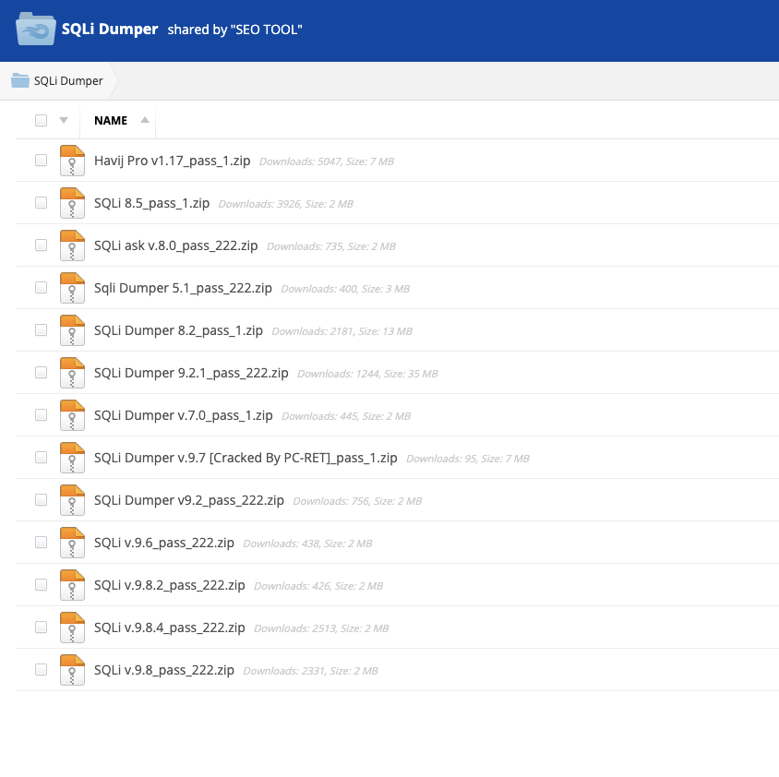

Important note: RTN’s forum was inaccessible as of writing this report - we cannot determine if the trojanized files have anything to do with the original creators of the keygens made by RTN. However, the mediafire file hosting website contains the trojanized file and many other cracked versions of tools:

Trojanized files in MediaFire file share.

Trojanized files in MediaFire file share.

When looking for the page that leads to this file share, a blog hosted on Blogspot was found which offers many cracked hacking and the aforementioned trojanized tools, linking to the above mentioned MediaFire file share:

As mentioned above, this campaign appears to have been going on for several years. So far, we have found samples that are either pretending to be various hacking tools or pretending to be installers of the Chrome Internet browser. There are around 700 samples associated with the *.capeturk.com subdomain, and there are more samples added to various threat intelligence resources on a daily basis.

PDB Artifacts

As described in the malware analysis section of this writeup, it appears that the PDB path embedded in the malware samples contains valuable information on how the malware is packed, as can be seen in the following examples. Each example is taken from a different sample:

- C:\Users\pc\Desktop\25-8-2019\3 lop-GZip+poly Xor base64\GZip+poly Xor base64 builder\WindowsApplication2\obj\Release\WindowsApplication2.pdb

- C:\Users\pc\Downloads\Gen code PolyRSM RC4 Poly AES Gzip Builder 21-09-2018\PolyRSM RC4 Poly AES Gzip 26-07-2018\PolyRSM +RC4+ Poly AES +Gzip Builder 07-01-2015\obj\x86\Release\explorer.pdb

- C:\Users\pc\Desktop\xxxxx\ALL PolyRSM +RC4+ Poly AES +Gzip StrReverse 11-01-2019\PolyRSM +RC4+ Poly AES +Gzip Builder StrReverse 11-01-2019\obj\x86\Release\explorer.pdb

- C:\Users\pc\Desktop\03-02-2020\ZIP RC2 RC4\decode\WindowsApplication6\obj\Release\explorer.pdb

- C:\Users\pc\Desktop\03-02-2020\NEW 3DES ZIP 29-01-2020\decode\WindowsApplication6\obj\Release\taskhost.pdb

These are just four examples out of hundreds of files. It’s worth noting that each example has different dates. Some are very recent, while others are from a few years ago. This suggests that compilation of these malicious files is automated.

The Domain

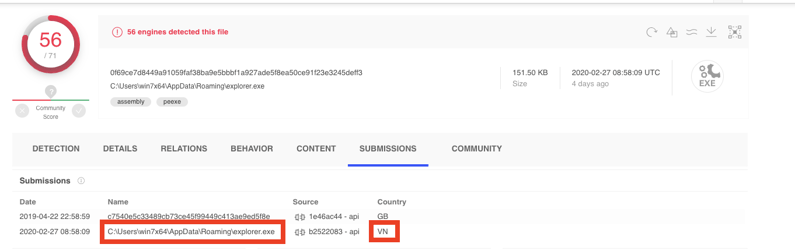

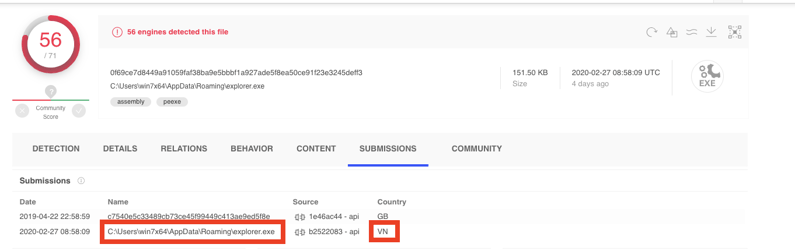

Until June 2018, it seems capeturk.com was a Turkish gaming website dedicated to the well-known game Minecraft. On November 25 2018, the capeturk.com domain expired and was registered by a Vietnamese individual. The domain started to be associated with malware around the time of the re-registration, however, it is unclear whether this Vietnamese individual has any ties to the malware campaign. That being said, it seems someone from Vietnam is constantly testing the samples by submitting them to VirusTotal. We suspect this individual is tied to the Vietnamese domain ownership:

VirusTotal submissions page from one of the samples.

Important note: According to the highlighted path from the submission information and the win7x64 username in the path, this is some sort of test machine. Additionally, this sample was submitted from Vietnam.

Multiple campaigns and targets?

After examining different samples submitted to different subdomains of capeturk.com (as detailed in the IOCs section of this writeup) it appears that each subdomain is targeting different software and therefore a different set of victims. While all of the samples associated with blog.capeturk.com are targeting various penetration testing and hacking tools, other subdomains are targeting Chrome installers, native Windows applications, and other random programs that have nothing to do with hacking or penetration testing.

For example, this sample which is connecting to 6666.elitfilmizle.com, is another njRat payload pretending to be an NVIDIA service:

Another important behavior to note is that the numbers in the subdomain (6666, 7777, etc) correspond to the port on which the C2 server is running on the host. For example, 6666.elitfilmizle.com has port 6666 listening on it, 7777.elitfilmizle.com has port 7777, and so on.

Conclusion

This investigation surfaced almost 1000 njRat samples compiled and built on almost a daily basis. It is safe to assume that many individuals have been infected by this campaign (although at the moment we are unable to know exactly how many). This campaign ultimately gives threat actors complete access to the target machine, so they can use it for anything from conducting DDoS attacks to stealing sensitive data off the machine.

It is clear the threat actors behind this campaign are using multiple servers, some of which appear to be hacked WordPress blogs. Others appear to be the infrastructure owned by the threat group, judging by multiple hostnames, DNS data, etc.

At the moment, we are unable to ascertain the other victims this malware campaign is targeting, other than those targeted by the trojanized hacking tools connecting to the “7777 server”. We will continue to monitor this campaign for any further developments.

Check out how we use MITRE ATT&CK to identify and categorize threats like Operation Soft Cell in our webinar with the MITRE ATT&CK team.

Indicators of Compromise

Click here to download this campaign's IOCs (PDF)

MITRE ATT&CK BREAKDOWN

Click here to view the njRat Threat Alert or browse our existing threat alerts below.