The Cybereason Global Security Operations Center (GSOC) Team issues Threat Analysis Reports to inform on impacting threats. The Threat Analysis Reports investigate these threats and provide practical recommendations for protecting against them.

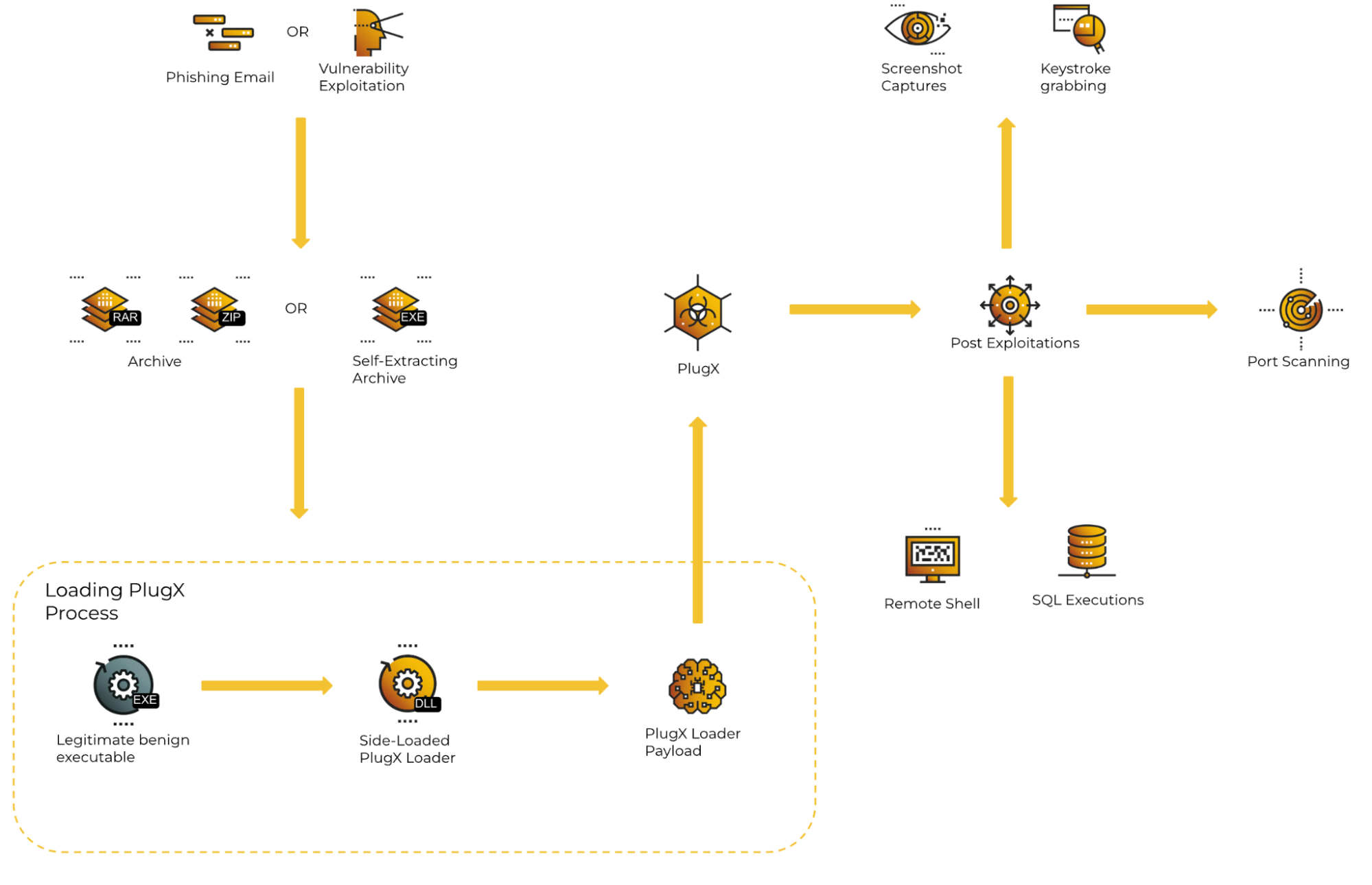

In this Threat Analysis report, the Cybereason GSOC investigates the PlugX malware family, a modular Remote Access Tool/Trojan (RAT) often utilized by Asia-based APT groups such as APT27. The malware has backdoor capabilities to take full control of the environment with its many malicious “plugins.”

This report provides an overview of the PlugX loader as well as modifications across multiple samples (six in total) starting from the year 2012 to 2022.

Key Points

- The Rule of Three: The malware may be delivered differently depending on the campaigns such as whether the initial delivering format is self de-archiving or not. However, the PlugX loader always consists of three main components: a legitimate executable, a malicious module, and a malicious payload. The malware has been around for over a decade, but the format of the malware has not changed.

- Security Evasion-Focused Techniques: PlugX loader is known for utilizing DLL-Sideloading techniques for evasion purposes. However, the malware is packing additional evasion techniques. This increases the chance of deploying the main PlugX payload successfully.

Introduction

PlugX is a post-exploitation modular RAT (Remote Access Trojan), which, among other things, is known for its multiple functionalities such as data exfiltration, keystroke grabbing, and backdoor functionality. The malware’s first publications and research papers date back to 2012.

However, according to Trend Micro, the malware has actually been around since 2008. PlugX was already making a name for itself back in 2012 due to high activity within Asia.

This may have been due to the fact that the PlugX malware authors were tied to China and the operators of this malware at the time were located within Asian countries. Since then, the malware has been active and utilized by many threat actors for over the past decade. The malware had many updates over the years and it does not appear to be going away anytime soon.

From its original version, the PlugX malware has been primarily used against public-sector organizations such as governments and various political organizations. In addition, advanced threat actors utilize the malware heavily to target high profile private organizations.

For example, in June 2016, Japan’s leading tourism agency announced the leak of privacy data of 7.93 million users, which was later identified by Trellix as an attack utilizing PlugX. The malware was also seen utilized outside of Asian countries when it targeted military and aerospace interests in Belarus and Russia.

This may be the indicator that the malware operators for PlugX were expanding their markets and targets. Most recently, the malware was utilized to target European government agencies which aided Ukrainian refugees from the recent Russia-Ukraine War.

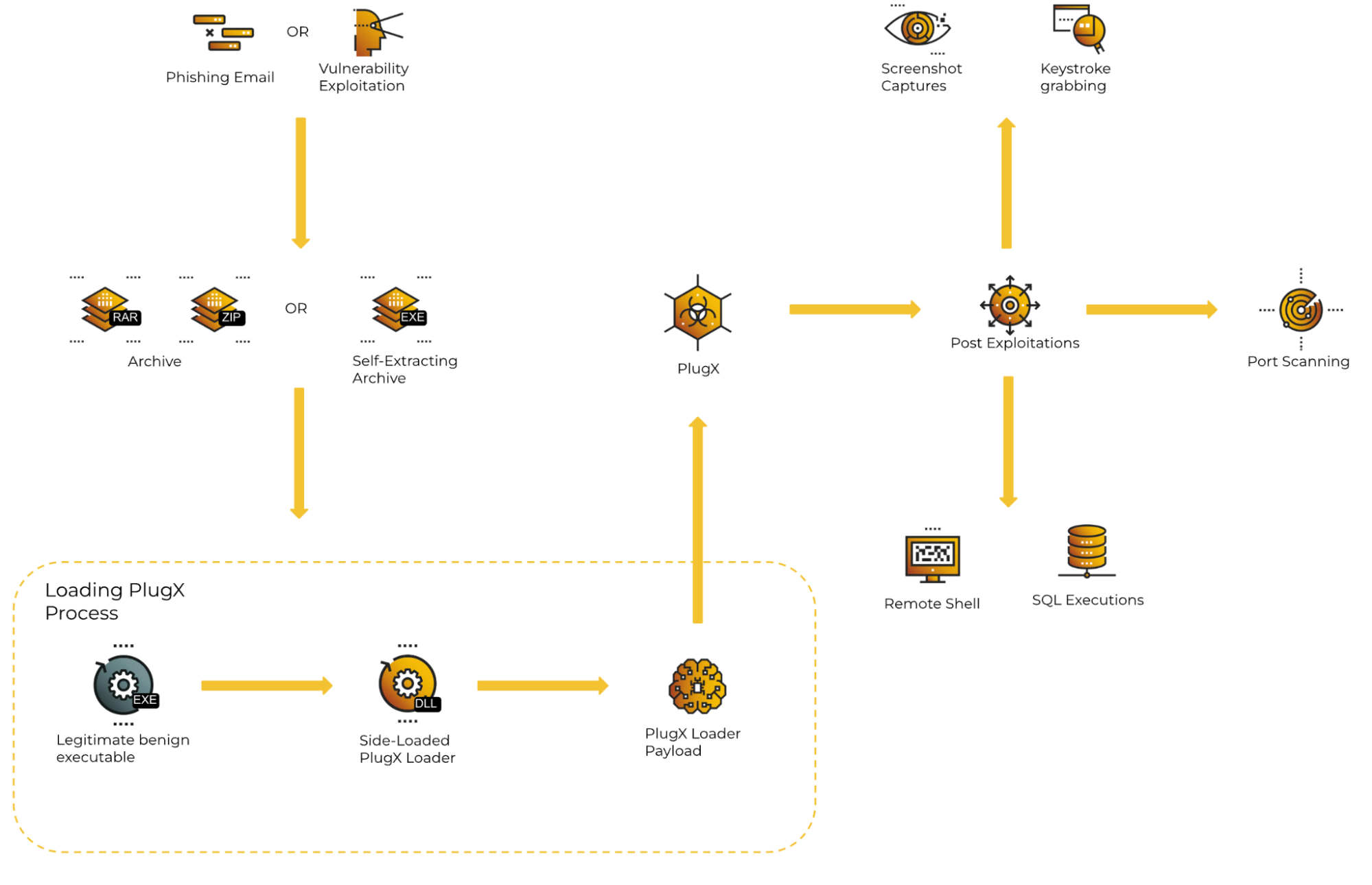

PlugX loader is commonly delivered via phishing emails and it is also seen delivered by exploiting a vulnerability such as ProxyLogon according to Unit 42 from Palo Alto Networks. The malware is often delivered as an archived formatted file such as .zip, .rar or self-extracting RAR (SFX) archive.

Within this archived file format, the malware contains three main files:

- legitimate executable

- malicious module

- malicious payload

The malware utilizes DLL Side-Loading as a main method to load a malicious DLL from a legitimate executable, like Acrobat Reader or a legacy Microsoft binary, for instance. The benefits of using DLL Side-Loading is that the malware can hijack and masquerade the legitimate executable by loading malicious modules. DLL Side-loading not only allows for evasion of security tools, but also allows malware developers to have a variety of options into which legitimate executable to side-load the PlugX payload:

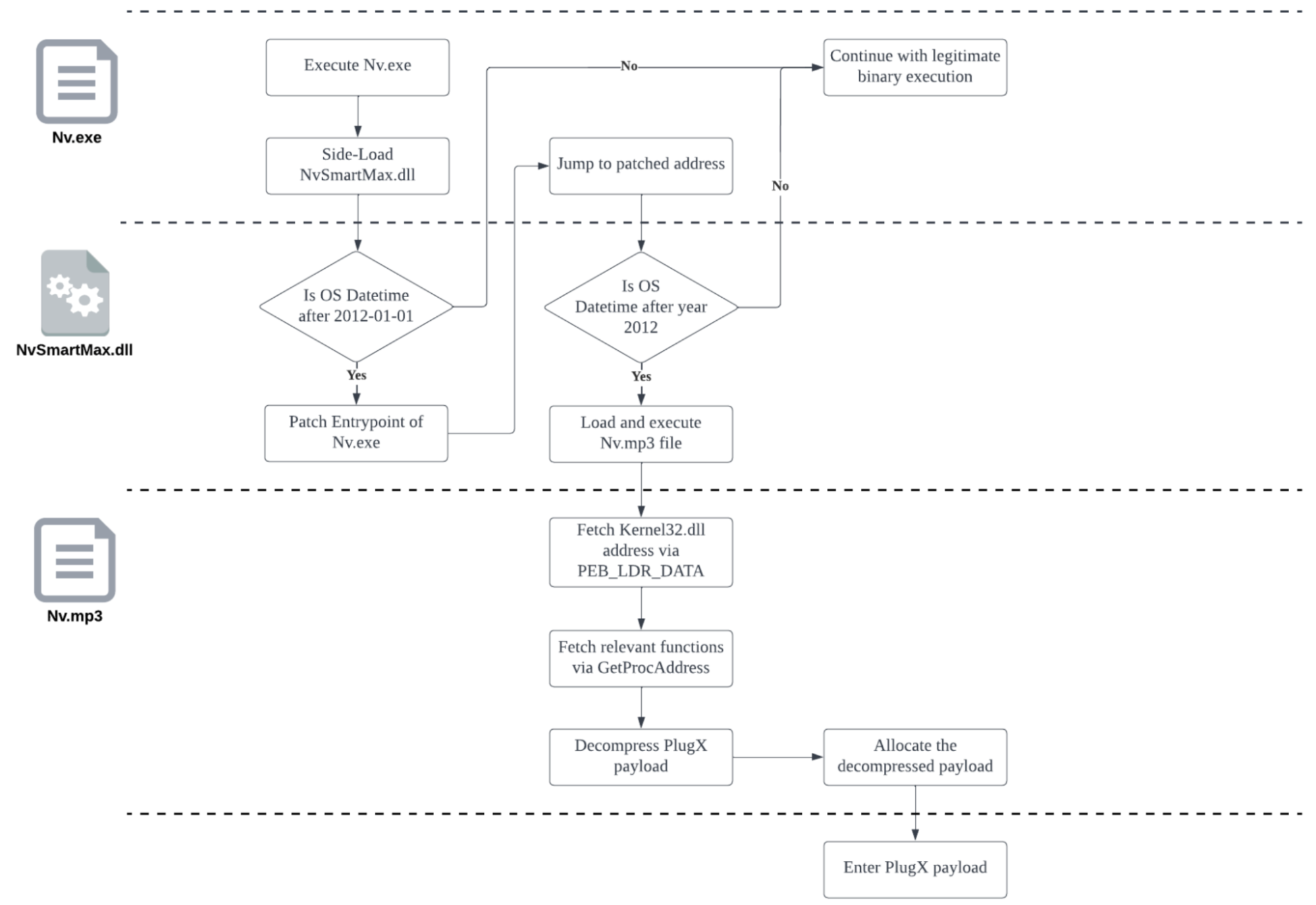

PlugX infection flow. View Loading PlugX Process FlowChart

DLL Side-Loading is one of many evasive aspects that this malware has in its arsenal, and which this analysis describes in depth:

Technical Analysis

The technical analysis focuses on the PlugX loader’s deployment method and specifically PlugX Loader Analysis focuses on three files with the following sample Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA)-256. These files were introduced in this article from 2012:

|

Filename

|

SHA-256

|

|

Nv.exe (legitimate)

|

523D28DF917F9D265CD2C0D38DF26277BC56A535145100ED82E6F5FDEAAE7256

|

|

NvSmartMax.dll

|

EAAA7899B37A3B04DCD02AD6D51E83E035BE535F129773621EF0F399A2A98EE3

|

|

Nv.mp3

|

3D64E638F961B922398E2EFAF75504DA007E41EA979F213F8EB4F83E00EFEEBB

|

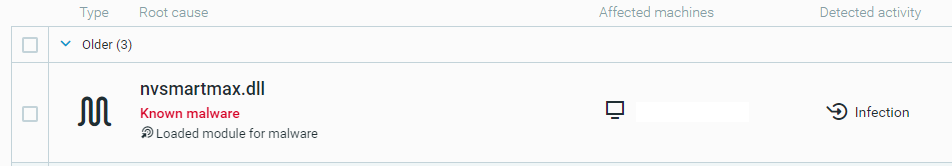

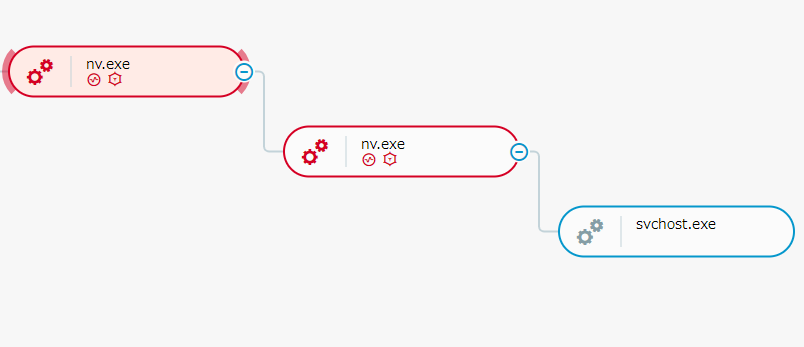

The malware utilizes DLL Side-Loading technique by leveraging the legitimate executable (Nv.exe) to load a malicious module (NvSmartMax.dll), which loads an additional malicious payload (Nv.mp3) to prepare for an actual PlugX payload.

The Comparative Analysis compares different PlugX loader samples to provide the modifications of deployment methods.

PlugX Loader Analysis

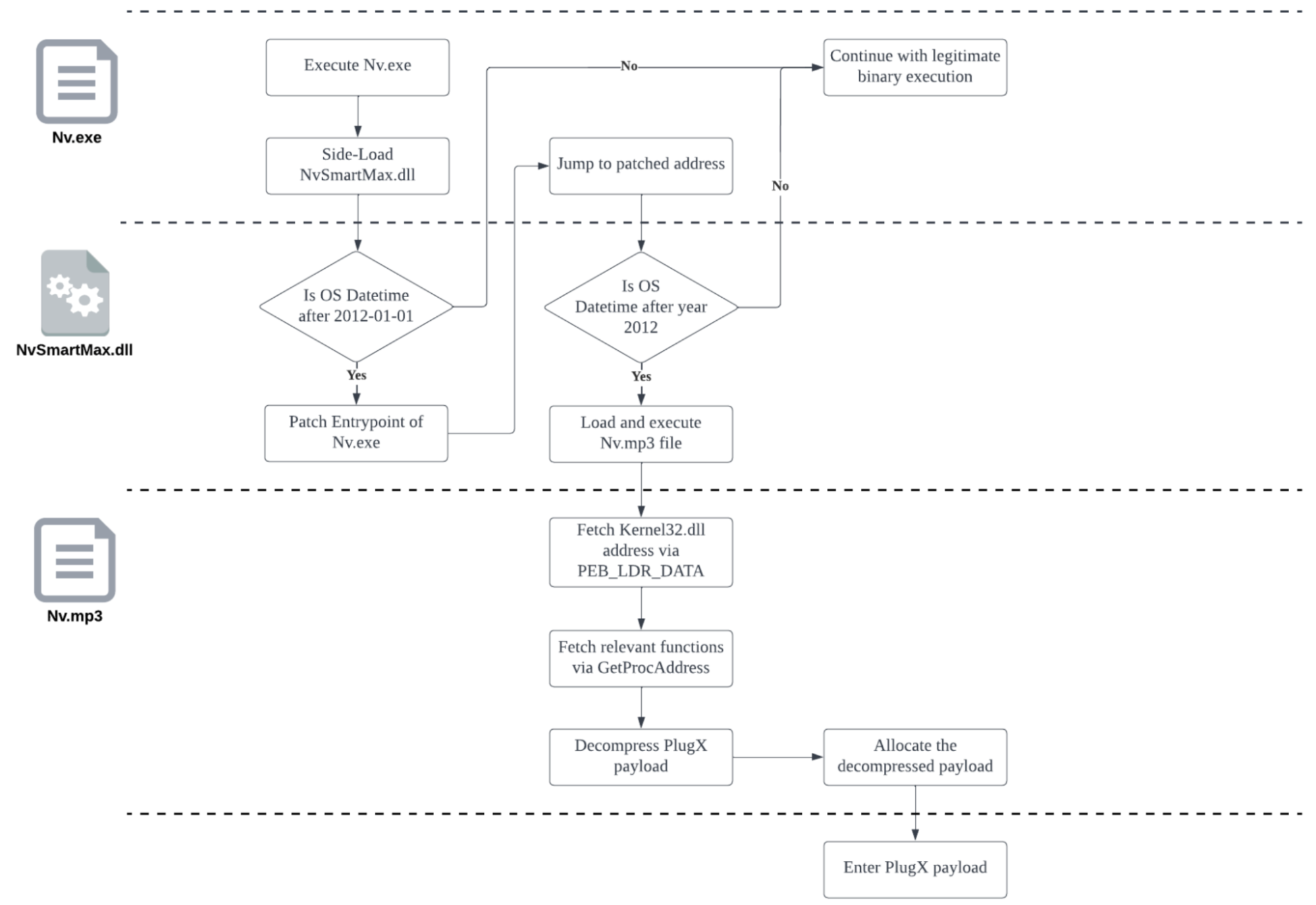

This section describes the deployment of the PlugX loader in the specific case of the use of Nv.exe as the DLL side-loader. The chapter ends with the PlugX payload loaded in memory:

PlugX Loader Summary

OS Datetime Check

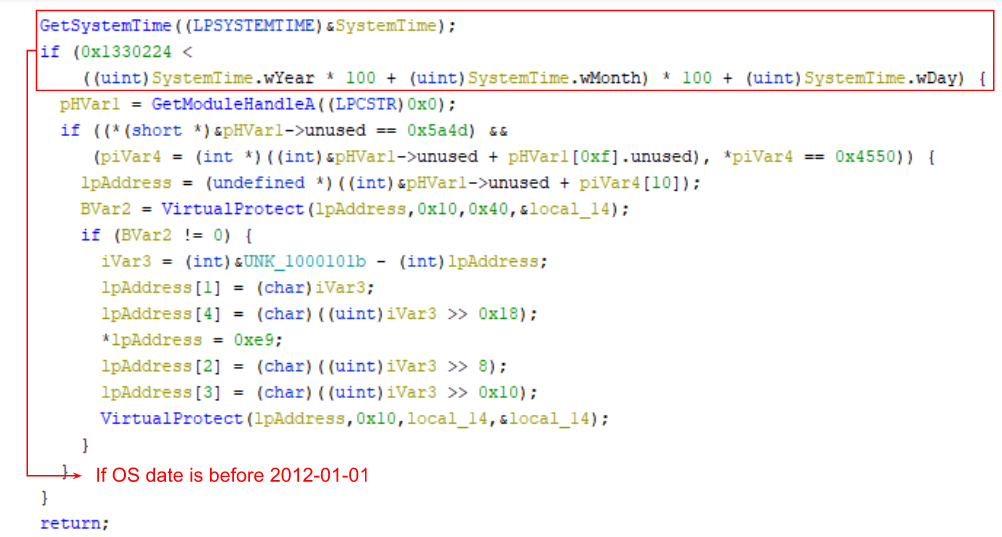

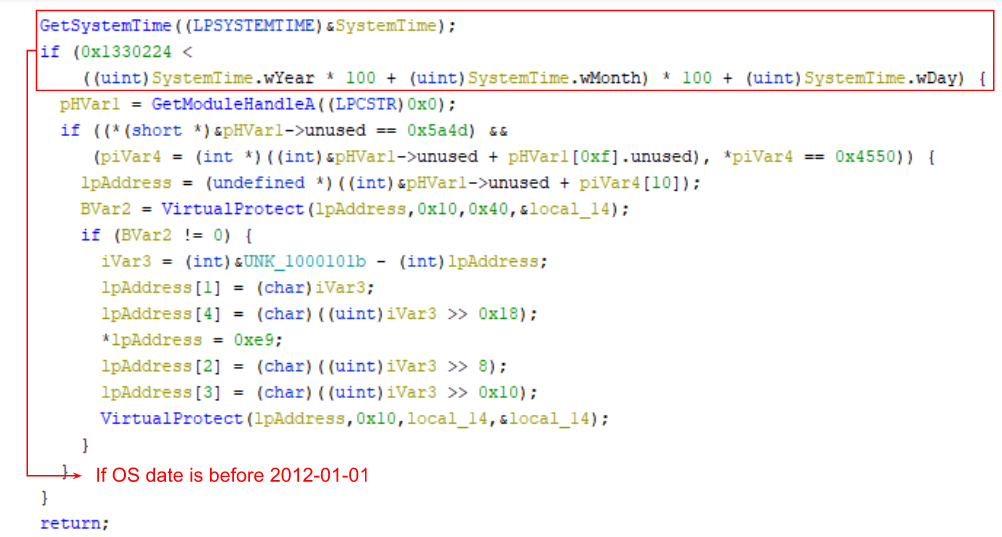

When the legitimate executable Nv.exe first executes and side-loads the PlugX loader module NvSmartMax.dll, the module first checks the OS date and time with the GetSystemTime method, which then calculates the output with the following formula.

Result = ( (OS_Year * 100) + OS_Month ) * 100 + OS_Date

The result of the equation is expected to be a hex value, which is then compared with the value 0x1330225, which is equivalent to the date 2012-01-01. The execution of this method enables the NvSmartMax.dll to check if the OS date and time is later than 2012-01-01.

If the date and time is later than 2012-01-01, the DLL execution exits. This checking mechanism is assumed to be for malware’s release purpose and prohibits its usage before its official release:

OS datetime check

Control Flow Manipulation

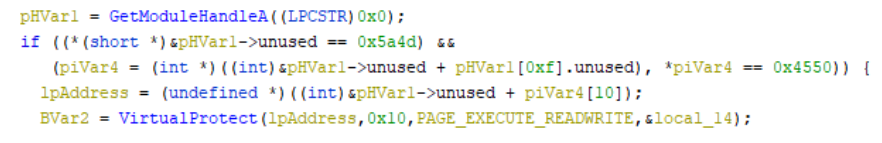

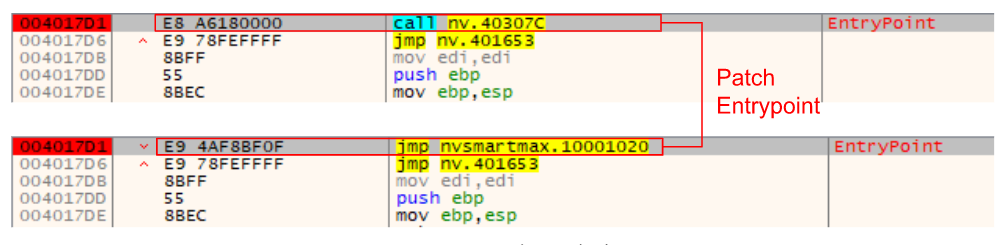

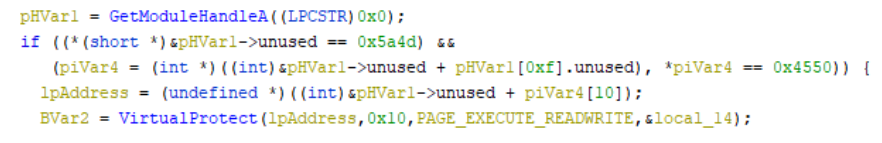

After the OS date and time is confirmed to be later than 2012-01-01, the NvSmartMax.dll fetches the address of Nv.exe’s EntryPoint and proceeds to update the page protection of the EntryPoint by calling the VirtualProtect function. NvSmartMax.dll updates the Nv.exe’s EntryPoint’s page protection to PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE to prepare a modification on the EntryPoint:

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE

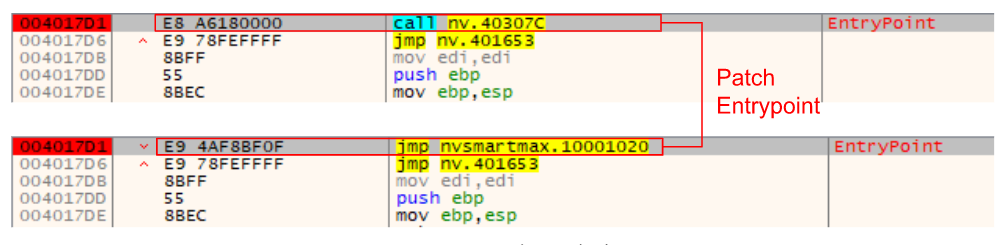

The NvSmartMax.dll module proceeds to patch the EntryPoint to jump into a function at offset 0x1020 in NvSmartMax.dll. The malware appears to be utilizing control flow manipulation as an obfuscation method against static analysis:

Nv.exe’s entry point patched

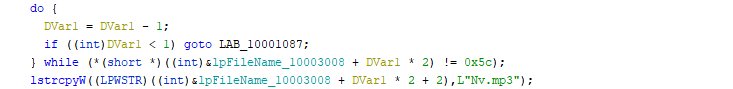

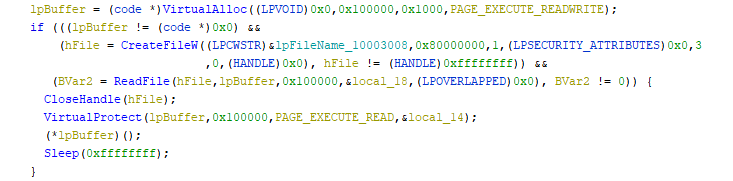

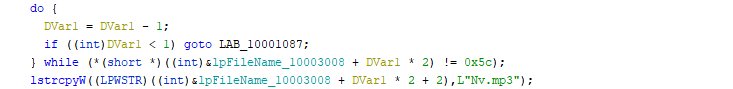

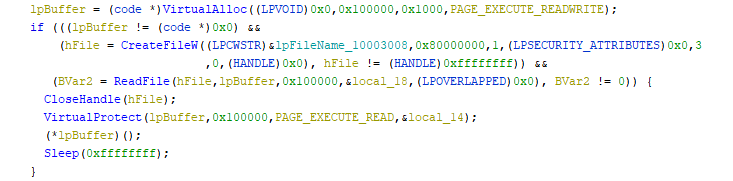

Once the control flow enters the EntryPoint of the Nv.exe, execution jumps to the patched address in NvSmartMax.dll. In the target function, the malware prepares to load the Nv.mp3 by attempting the following steps:

- Check the OS date and time again - however, during this check, the verification checks for the year 2012

- Prepare the malware file

- Allocate memory

- Read Nv.mp3 into allocated memory

- Update page protection to PAGE_EXECUTE_READ

- Execute code located at Nv.mp3

Prepare payload file name

Allocate and enter the payload

InInitialization Order Module List

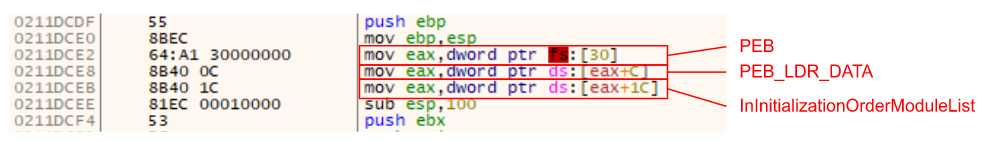

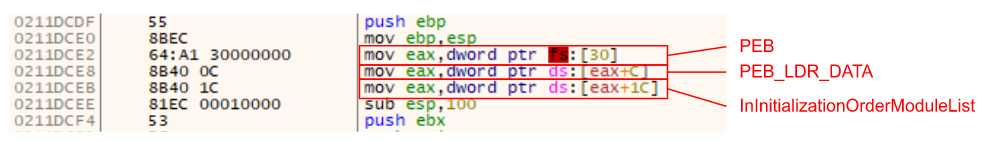

Once the control flow accesses the Nv.mp3 memory region, it dynamically fetches the loaded module kernel32.dll’s base address from the InInitializationOrderModuleList within the Process Environment Block (PEB).

PEB is a data structure, which contains process information which is utilized internally by the operating system (OS). PEB is often utilized for anti-analysis techniques such as NtGlobalFlag check, but it can also be used to fetch necessary module information.

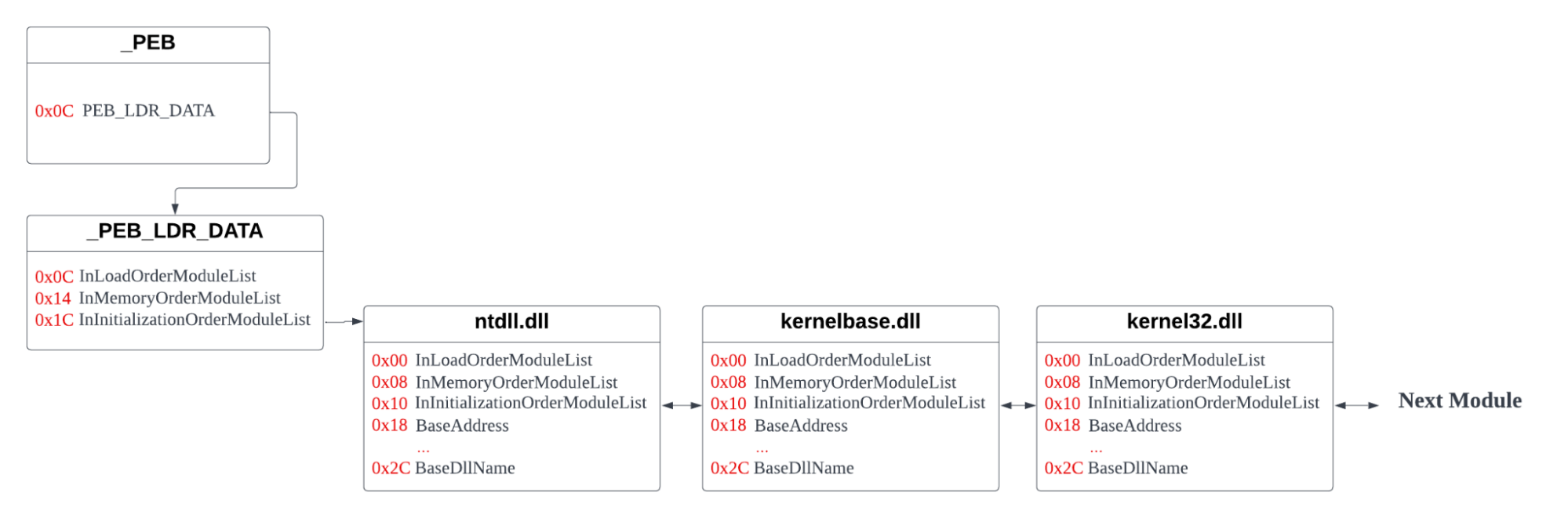

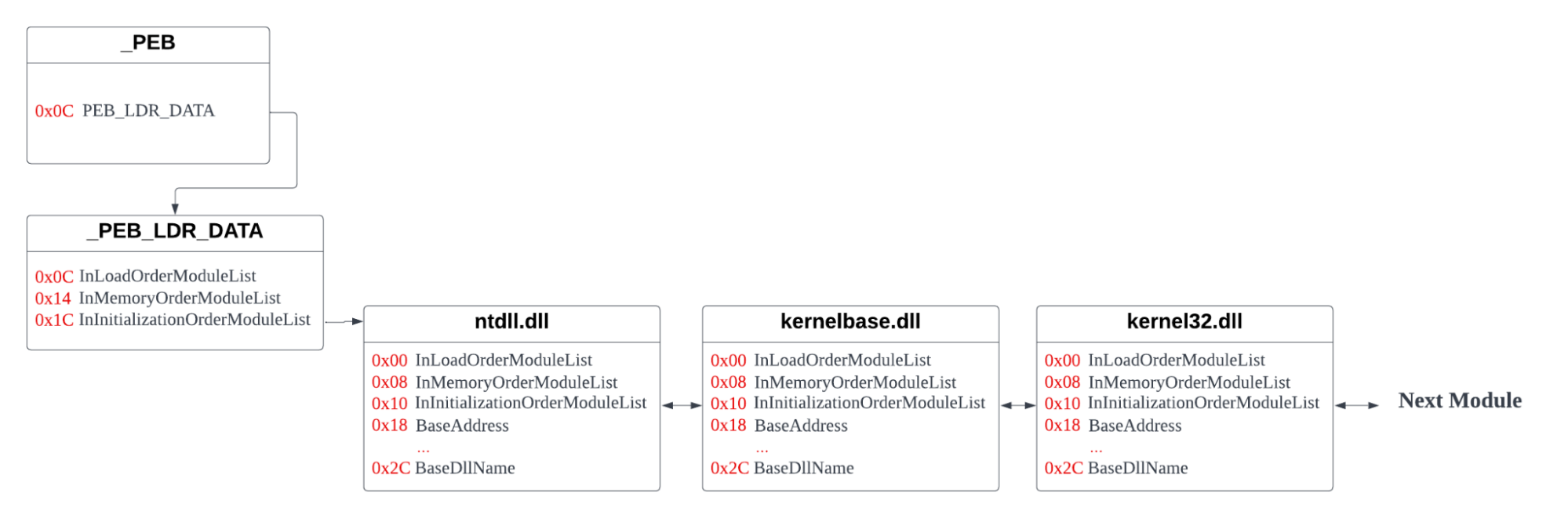

At offset 0x0C within PEB, PEB_LDR_DATA structure is located which stores loaded module information. This structure has three members: InLoadOrderModuleList, InMemoryOrderModuleList, and InInitializationOrderModuleList:

Fetching loaded modules from PEB_LDR_DATA

The code located in Nv.mp3 fetches InInitializationOrderModuleList, which includes all the loaded modules in order of initialization. This list does not include the executable itself, and it only lists the modules:

InitializationOrderModuleList diagram

The Nv.mp3 searches through each element’s BaseDllName, until it finds kernel32.dll and retrieves the BaseAddress of the module.

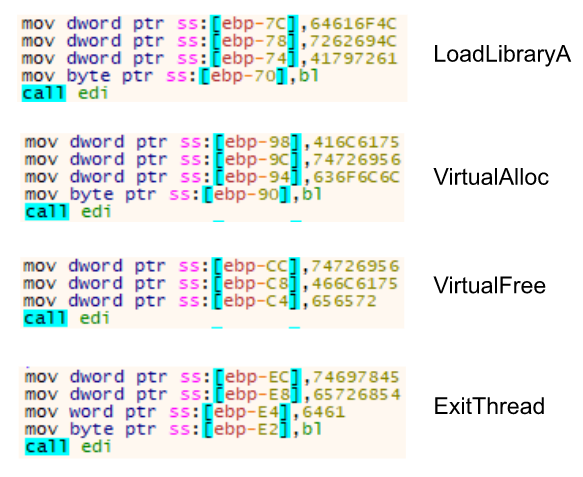

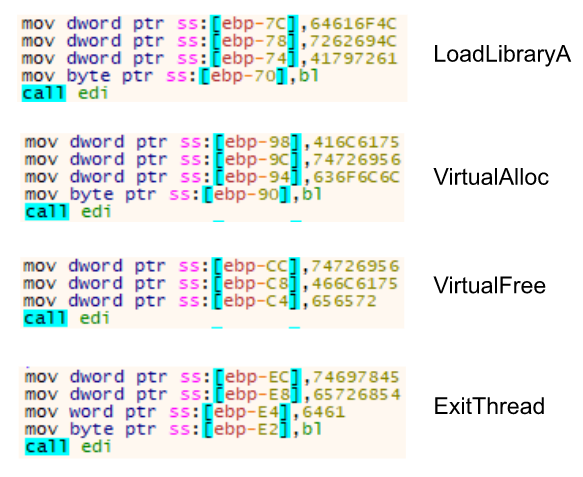

Once the base address of kernel32.dll is retrieved, Nv.mp3 fetches the function GetProcAddress address in order to load the functions LoadLibraryA, VirtualAlloc, VirtualFree, and ExitThread, which appears to be loaded via StackString method:

StackString libraries

Once all the function addresses are loaded from kernel32.dll, Nv.mp3 loads the module ntdll.dll by using the LoadLibraryA function which was retrieved earlier by the GetProcAddress function. From ntdll.dll, Nv.mp3 loads functions RtlDecompressBuffer and memcpy.

Plugx Payload Decompression

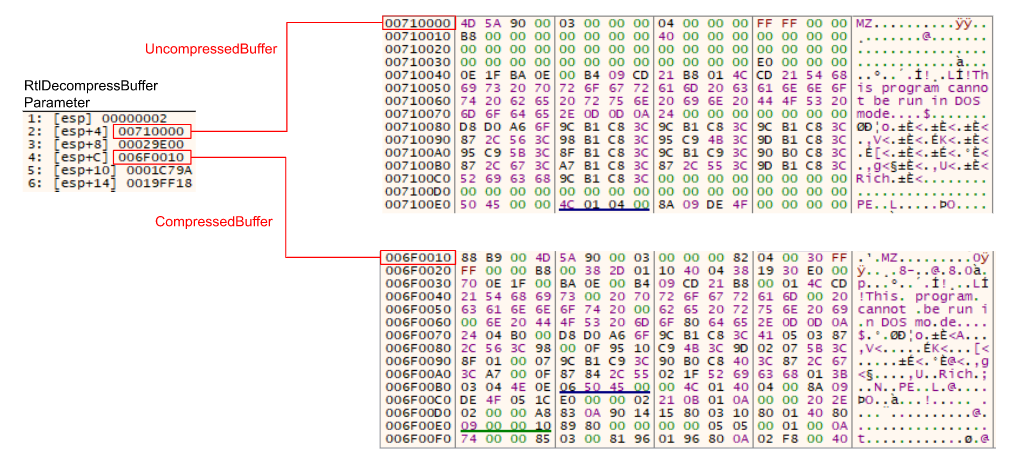

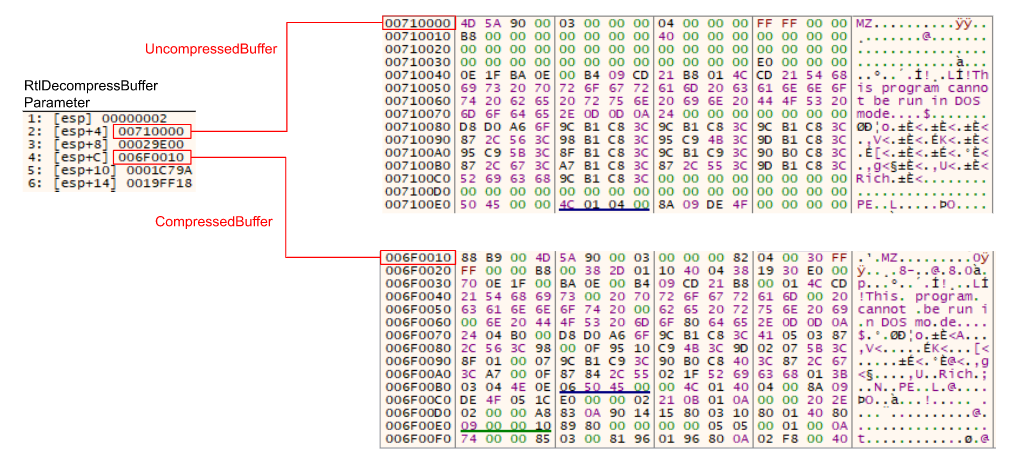

The code located at Nv.mp3 level proceeds to decrypt the RC4-encrypted strings which are stored within the payload at offset 0x1529 with size 117KB. The decrypted strings are a compressed version of a PE file, which performs the RtlDecompressBuffer function with LZ decompression format:

NT_RTL_COMPRESS_API NTSTATUS RtlDecompressBuffer(

[in] USHORT CompressionFormat,

[out] PUCHAR UncompressedBuffer,

[in] ULONG UncompressedBufferSize,

[in] PUCHAR CompressedBuffer,

[in] ULONG CompressedBufferSize,

[out] PULONG FinalUncompressedSize

);

Figure 11: RtlDecompressBuffer Function Parameters

Decompressed Buffer

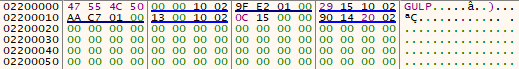

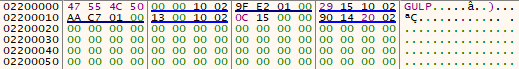

The decompressed PE file is an actual PlugX itself. However, the control flow does not immediately enter the decompressed payload. Nv.mp3 places the “GULP” signature, which is the backward for “PLUG” in newly allocated memory by VirtualAlloc with PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE protection. It proceeds to allocate each section’s .text, .rdata, .data, and .reloc by using the memcpy function into allocated memory.

Lastly, it loads necessary libraries and functions dynamically by using LoadLibraryA and GetProcAddress from the import table listed in the decompressed PE file. Once this preparation is done, it proceeds to enter the PlugX payload:

PlugX payload header

PlugX payload header

PlugX Loader Flowchart

The following flowchart summarizes the flow of the PlugX loader:

Figure 14: PlugX loader flowchart

Comparative Analysis

This comparative analysis analyzes the following six samples listed in the table below. The samples are observed in the past from various analyses from different reports. As a reference, the samples (executable, module, payload) are identified with codename with prefix px_ followed by the relevant year that the samples were observed according to the external sources:

|

Codename

|

Filename

|

SHA-256

|

|

px_2012

|

Nv.exe

|

523D28DF917F9D265CD2C0D38DF26277BC56A535145100ED82E6F5FDEAAE7256

|

|

NvSmartMax.dll

|

EAAA7899B37A3B04DCD02AD6D51E83E035BE535F129773621EF0F399A2A98EE3

|

|

Nv.mp3

|

3D64E638F961B922398E2EFAF75504DA007E41EA979F213F8EB4F83E00EFEEBB

|

|

px_2014

|

Gadget.exe

|

5C859CA16583D660449FB044677C128A9CDEDD603D9598D4670235C52E359BF9

|

|

Sidebar.dll

|

4B23F8683E184757E8119C8C68063F547F194E1ABD758DCBD4DACF70E3908FC1

|

|

Sidebar.dll.doc

|

B2B93C7C4AC82623F74B14FE73F2C3F8E58E3306CC903C5AE71BC355CB5BD069

|

|

px_2015

|

fsguidll.exe

|

5C5E3201D6343E0536B86CB4AB0831C482A304C62CD09C01AC8BDEEE5755F635

|

|

fslapi.dll

|

96876D24284FF4E4155A78C043C8802421136AFBC202033BF5E80D1053E3833F

|

|

fslapi.dll.gui

|

ACDC4987B74FDF7A32DFF87D56C43DF08CCE071B493858E3CE32FCF8D6372837

|

|

px_2019

|

mcinsupd.exe

|

507D49186748DD83D808281743A17FCA4B226883C410EC76EB305360CBC8C091

|

|

mytilus3.dll

|

9FB33E460CA1654FCC555A6F040288617D9E2EFE626F611B77522606C724B59B

|

|

mytilus3.dump

|

6914E9DE21F5CCE3F5C1457127122C13494ED82E6E2D95A8200A46BDB4CD7075

|

|

px_2021

|

aro.exe

|

18A98C2D905A1DA1D9D855E86866921E543F4BF8621FAEA05EB14D8E5B23B60C

|

|

aross.dll

|

9FFFB3894B008D5A54343CCF8395A47ACFE953394FFFE2C58550E444FF20EC47

|

|

aro.dat

|

59BA902871E98934C054649CA582E2A01707998ACC78B2570FEF43DBD10F7B6F

|

|

px_2022

|

RasTls.exe

|

F9EBF6AEB3F0FB0C29BD8F3D652476CD1FE8BD9A0C11CB15C43DE33BBCE0BF68

|

|

RasTls.dll

|

6CD5079A69D9A68029E37F2680F44B7BA71C2B1EECF4894C2A8B293D5F768F10

|

|

RasTls.dll.res

|

37B3FB9AA12277F355BBB334C82B41E4155836CF3A1B83E543CE53DA9D429E2F

|

Each sample is compared based on the configuration and implementation of the PlugX loader:

- Malware’s release date control with OS datetime check

- Manipulation of control flow by patching the instructions within the executable for anti-analysis

- Dynamically retrieving module kernel32.dll’s base address within payload by utilizing the PEB_LDR_DATA structure

- Code obfuscation within the payload for anti-analysis

- Decompression preparation of PlugX payload and the format of the payload

OS Datetime

As explained in the previous section, PlugX loader does check that the date is later than a specific value. This behavior has been observed on three samples, from this list of six samples:

|

Sample

|

Check count

|

Datetime

|

|

px_2012

|

2

|

2012-01-01, 2012

|

|

px_2014

|

2

|

2012-01-01, 2012

|

|

px_2015

|

0

|

N/A

|

|

px_2019

|

1

|

2018

|

|

px_2021

|

0

|

N/A

|

|

px_2022

|

0

|

N/A

|

The date and time check happens twice in samples px_2012 and px_2014:

- Checks the date before executing the instruction patching function

- Checks the year before allocating the PlugX loader payload file

However, in sample px_2019, it only conducts the date and time check for the year 2018. The versioning of this malware also seems to exist, which is evident from the date and time check of the date of px_2019 being 2018.

Manipulate Control Flow

|

Sample

|

Patch Instruction

|

Patched Instruction

|

|

px_2012

|

Yes

|

JMP

|

|

px_2014

|

No

|

N/A

|

|

px_2015

|

Yes

|

JMP

|

|

px_2019

|

Yes

|

PUSH/RET

|

|

px_2021

|

No

|

N/A

|

|

px_2022

|

Yes

|

PUSH/RET

|

Manipulation of the control flow by patching the instructions with JMP is utilized with the samples, however the samples px_2019 and px_2022 are patched with PUSH and RET instructions. The PUSH instruction “pushes” the relevant function address onto the stack and the RET instruction moves the control flow into the pushed address.

Samples px_2014 and px_2021 did not patch instructions to manipulate the control flow. It utilized legitimate exported function names of the legitimate DLL which gets called by the legitimate executable.

PEB_LDR_DATA

|

Sample

|

PEB_LDR_DATA

|

|

px_2012

|

InInitializationOrderModuleList

|

|

px_2014

|

InInitializationOrderModuleList

|

|

px_2015

|

InInitializationOrderModuleList

|

|

px_2019

|

InInitializationOrderModuleList

|

|

px_2021

|

InMemoryOrderModuleList

|

|

px_2022

|

InInitializationOrderModuleList

|

Aside from InitializationOrderModuleList, sample px_2021 utilized InMemoryOrderModuleList. InMemoryOrderModuleList lists loaded modules according to the memory placement. The difference from InInitializationOrderModuleList is that InMemoryOrderModuleList includes the executable within the list.

Payload Obfuscation

|

Sample

|

Usage of StackString

|

Usage of Code Obfuscation

|

|

px_2012

|

Yes

|

N/A

|

|

px_2014

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

px_2015

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

px_2019

|

Yes; Places one characters at a time

|

N/A

|

|

px_2021

|

Yes; Places one characters at a time

|

N/A

|

|

px_2022

|

Yes; Some, one character at a time, some in bulk.

|

N/A

|

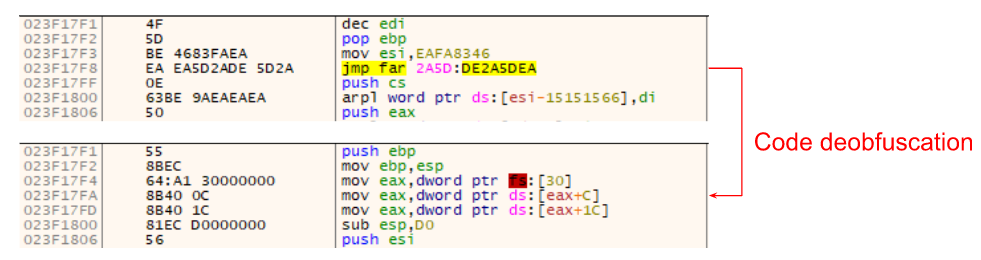

The usage of StackString on the functions which need to be loaded dynamically appears to be consistent throughout the samples. However, a slight update is placed in px_2019, px_2021 and px_2022, which is placing one character at a time onto a Stack:

Fetching VirtualProtect

Fetching VirtualProtect

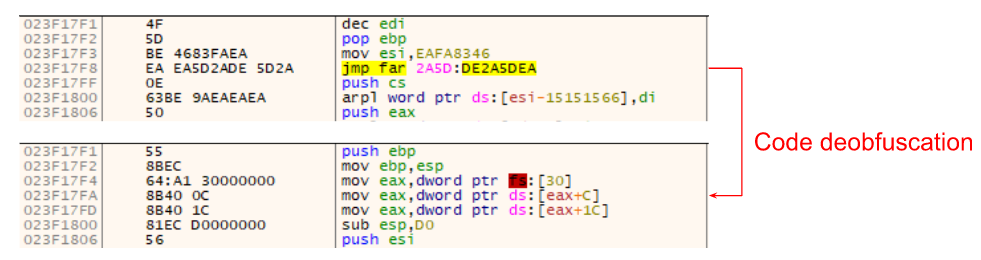

Samples px_2014 and px_2015 also have additional code obfuscation, which is an encryption on the function that prepares the PlugX payload. This function is the main component of this deployment payload and this is an additional layer of anti-analysis:

Code deobfuscation in px_2015

Decompression and Payload Deployment

|

Sample

|

Decompression Format

|

Decryption of compressed data

|

Decompressed Data Format

|

Payload Header

|

|

px_2012

|

LZ

|

Yes

|

PE File with PE signatures

|

GULP

|

|

px_2014

|

LZ

|

Yes

|

PE File with PE signatures

|

GULP

|

|

px_2015

|

LZ

|

Yes

|

PE File without PE signatures

|

XV

|

|

px_2019

|

LZ

|

Yes

|

PE File with PE signatures

|

GULP

|

|

px_2021

|

LZ

|

Yes

|

PE File without PE signatures

|

ROHT

|

|

px_2022

|

LZ

|

Yes

|

PE File with PE signatures

|

.PE

|

Decompression of PlugX payload is consistent across the samples, which decrypts the LZ compressed data. However, the decompressed payload for the samples px_2015 and px_2021 was not in complete PE file format. It was missing traditional PE signatures such as “MZ…This program cannot be run in DOS mode”. The relevant section information was still intact, which was needed for the PlugX loader to allocate necessary sections to the new memory region.

This update only removed portions of the PE header. However, it contained necessary information for the code to function. This update prevents analysts from simply dumping the decompressed payload and conducting further analysis, since it is not in proper PE format.

Sample px_2015, px_2021 and px_2022 also had different headers once the decompressed payload was allocated into PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE memory region:

- px_2015: XV - Roman numeral for 15.

- px_2021: ROHT - Backward for “THOR”

- px_2022: .PE - Portable Executable

The differences in the header may be evidence of the versioning of PlugX as well.

Core Deployment Methods Are Consistent Across Samples

There are several slight detail differences while comparing samples, however there appears to be no major updates in the past decade regarding the deployment method of this malware.

Although there were no major updates, the malware loader appears to have version management. This is evident from OS date and time check as well as the differences in payload headers while deploying the actual PlugX.

The lack of a major deployment method is also believed to be due to the use of the DLL Side-Loading technique. The DLL Side-Loading technique itself gives the threat actors various options on which legitimate executables to side-load the PlugX with. This evasion technique already creates various combinations and an update on deployment methods deemed unnecessary

Detection and Prevention

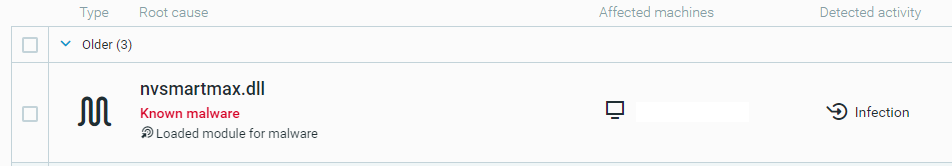

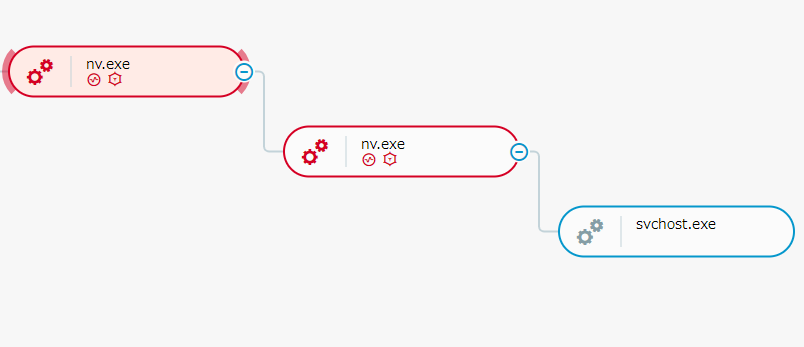

Cybereason Defense Platform

The Cybereason Defense Platform is able to detect and prevent infections with the PlugX loader using multi-layer protection that detects and blocks malware with threat intelligence, machine learning, anti-ransomware and Next-Gen Antivirus (NGAV) capabilities:

MalOp generation based from threat intelligence as seen in the Cybereason Defense Platform

Cybereason GSOC MDR

The Cybereason GSOC recommends the following:

- Enable both the Signature and Artificial Intelligence modes on the Cybereason NGAV, and enable the Detect and Prevent modes of this feature.

- Handle files originating from external sources (email, web browsing) with caution.

- To hunt proactively, use the Investigation screen in the Cybereason Defense Platform and the queries in the Hunting Queries section to search for machines that are potentially infected with PlugX. Based on the search results, take further remediation actions, such as isolating the infected machines and deleting the payload file.

Cybereason is dedicated to teaming with defenders to end cyber attacks from endpoints to the enterprise to everywhere. Schedule a demo today to learn how your organization can benefit from an operation-centric approach to security.

MITRE ATT&CK MAPPING

Indicators Of Compromise For PlugX Malware

|

Executables

|

SHA-256 hash:

EAAA7899B37A3B04DCD02AD6D51E83E035BE535F129773621EF0F399A2A98EE3

SHA-256 hash:

3D64E638F961B922398E2EFAF75504DA007E41EA979F213F8EB4F83E00EFEEBB

SHA-256 hash:

4B23F8683E184757E8119C8C68063F547F194E1ABD758DCBD4DACF70E3908FC1

SHA-256 hash:

B2B93C7C4AC82623F74B14FE73F2C3F8E58E3306CC903C5AE71BC355CB5BD069

SHA-256 hash:

96876D24284FF4E4155A78C043C8802421136AFBC202033BF5E80D1053E3833F

SHA-256 hash:

ACDC4987B74FDF7A32DFF87D56C43DF08CCE071B493858E3CE32FCF8D6372837

SHA-256 hash:

9FB33E460CA1654FCC555A6F040288617D9E2EFE626F611B77522606C724B59B

SHA-256 hash:

6914E9DE21F5CCE3F5C1457127122C13494ED82E6E2D95A8200A46BDB4CD7075

SHA-256 hash:

9FFFB3894B008D5A54343CCF8395A47ACFE953394FFFE2C58550E444FF20EC47

SHA-256 hash:

59BA902871E98934C054649CA582E2A01707998ACC78B2570FEF43DBD10F7B6F

SHA-256 hash:

6CD5079A69D9A68029E37F2680F44B7BA71C2B1EECF4894C2A8B293D5F768F10

SHA-256 hash:

37B3FB9AA12277F355BBB334C82B41E4155836CF3A1B83E543CE53DA9D429E2F

|

About The Researchers

Kotaro Ogino, Senior Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Kotaro Ogino is a Senior Security Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC team. He is involved in threat hunting, administration of Security Orchestration, Automation, and Response (SOAR) systems, and Extended Detection and Response (XDR). Kotaro has a bachelor of science degree in information and computer science.

Yuki Shibuya, Senior Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Yuki Shibuya is a Senior Security Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC team. He is tasked with triaging critical incidents, threat hunting and malware research. He has a master degree of information systems security and is interested in malware research and penetration testing.

Big thanks to Aleksandar Milenkoski for advising the research!