Dubbed Operation Cobalt Kitty, the APT targeted a global corporation based in Asia with the goal of stealing proprietary business information. The threat actor targeted the company’s top-level management by using spear-phishing attacks as the initial penetration vector, ultimately compromising the computers of vice presidents, senior directors and other key personnel in the operational departments. During Operation Cobalt Kitty, the attackers compromised more than 40 PCs and servers, including the domain controller, file servers, Web application server and database server.

Want to hear about another high-impact operation?

OPERATION COBALT

Forensic artifacts revealed that the attackers persisted on the network for at least a year before Cybereason was deployed. The adversary proved very adaptive and responded to company’s security measures by periodically changing tools, techniques and procedures (TTPs), allowing them to persist on the network for such an extensive period of time. Over 80 payloads and numerous domains were observed in this operation - all of which were undetected by traditional security products deployed in the company’s environment at the time of the attack.

The attackers arsenal consisted of modified publicly-available tools as well as six undocumented custom-built tools, which Cybereason considers the threat actor’s signature tools. Among these tools are two backdoors that exploited DLL sideloading attack in Microsoft, Google and Kaspersky applications. In addition, they developed a novel and stealthy backdoor that targets Microsoft Outlook for command-and-control channel and data exfiltration.

Based on the tools, modus operandi and IOCs (indicators of compromise) observed in Operation Cobalt Kitty, Cybereason attributes this large-scale cyber espionage APT to the “OceanLotus Group” (which is also known as, APT-C-00, SeaLotus and APT32). For detailed information tying Operation Cobalt Kitty to the OceanLotus Group, please see our Attacker’s Arsenal and Threat Actor Profile sections.

Cybereason also attributes the recently reported Backdoor.Win32.Denis to the OceanLotus Group, which at the time of this report’s writing, had not been officially linked to this threat actor.

Finally, this report offers a rare glimpse into what a cyber espionage APT looks like "under-the-hood". Cybereason was able to monitor and detect the entire attack lifecycle, from infiltration to exfiltration and all the steps in between.

Our report contains the following detailed sections (PDF):

- Cobalt Kitty Lifecycle: A step-by-step analysis

- Cobalt Kitty Attacker’s Arsenal: Deep dive into the tools used in the APT

- Cobalt Kitty Threat Actor Profile and Indicators of Compromise

High-level attack outline: A cat-and-mouse game in four acts

The following sections outline the four phases of the attack as observed by Cybereason’s analysts, who were called to investigate the environment after the company’s IT department suspected that their network was breached but could not trace the source.

Phase one: Fileless operation (PowerShell and Cobalt Strike payloads)

Based on the forensic evidence collected from the environment, phase one was the continuation of the original attack that began about a year before Cybereason was deployed in the environment. During that phase, the threat actor operated a fileless PowerShell-based infrastructure, using customized PowerShell payloads taken from known offensive frameworks such as Cobalt Strike, PowerSploit and Nishang.

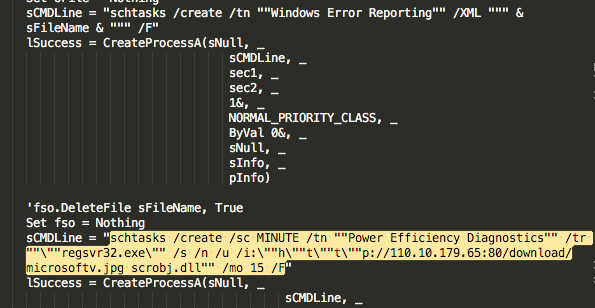

The initial penetration vector was carried out by social engineering. Carefully selected group of employees received spear-phishing emails, containing either links to malicious sites or weaponized Word documents. These documents contained malicious macros that created persistence on the compromised machine using two scheduled tasks, whose purpose was to download secondary payloads (mainly Cobalt Strike Beacon):

Scheduled task 1: Downloads a COM scriptlet that redirects to Cobalt Strike payload:

Scheduled task 2: Uses Javascript to download a Cobalt Strike Beacon:

See more detailed analysis of the malicious documents in our Attack Life Cycle section.

Fileless payload delivery infrastructure

In the first phase of the attack, the attackers used a fileless in-memory payload delivery infrastructure consisting of the following components:

- VBS and PowerShell-based loaders

The attackers dropped Visual Basic and PowerShell scripts in folders that they created under the ProgramData (a hidden folder, by default). The attackers created persistence using Windows’ registry, services and scheduled tasks. This persistence mechanism ensured that the loader scripts would execute either at startup or at predetermined intervals.

Values found in Windows’ Registry: the VBS scripts are executed by Windows’ Wscript at startup:

The .vbs scripts as well as the .txt files contain the loader’s script, which launches PowerShell with a base64 encoded command, which either loads another PowerShell script (e.g Cobalt Strike Beacon) or fetches a payload from the command-and-control (C&C) server:

- In-memory fileless payloads from C&C servers

The payloads served by the C&C servers are mostly PowerShell scripts with embedded base64-encoded payloads (Metasploit and Cobalt Strike payloads):

Example 1: PowerShell payload with embedded Shellcode downloading Cobalt Strike Beacon

The decoded payload is a shellcode, whose purpose is to retrieve a Cobalt Strike Beacon from the C&C server:

Example 2: Cobalt Strike Beacon embedded in obfuscated PowerShell

A second type of an obfuscated PowerShell payload consisted of Cobalt Strike’s Beacon payload:

Less than 48 hours after Cybereason alerted the company about the breach, the attackers started to change their approach and almost completely abandoned the PowerShell infrastructure that they had been using - replacing it with sophisticated custom-built backdoors. The attackers’ remarkable ability to quickly adapt demonstrated their skill and familiarity with and command of the company’s network and its operations.

The attackers most likely replaced the PowerShell infrastructure after the company used both Windows Group Policy Object (GPO) and Cybereason’s execution prevention feature to prevent PowerShell execution.

Phase two: Backdoors exploiting DLL-hijacking and using DNS tunneling

After realizing that the PowerShell infrastructure had been discovered, the attackers had to quickly replace it to maintain persistence and continue the operation. Replacing this infrastructure in 48 hours suggests that the threat actors were prepared for such a scenario.

During the second phase of the attack, the attackers introduced two sophisticated backdoors that they attempted to deploy on selected targets. The introduction of the backdoors is a key turning point in the investigation since it demonstrated the threat actor’s resourcefulness and skill-set.

At the time of the attack, these backdoors were undetected and undocumented by any security vendor. Recently, Kaspersky researchers identified a variant of one of the backdoors as Backdoor.Win32.Denis. The attackers had to make sure that they remained undetected so the backdoors were designed to be as stealthy as possible. To avoid being discovered, the malware authors used these techniques:

Backdoors exploiting DLL hijacking against trusted applications

The backdoor exploited a vulnerability called “DLL hijacking” in order to “hide” the malware inside trusted software. This technique exploits a security vulnerability found in legitimate software, which allows the attackers to load a fake DLL and execute its malicious code.

Please see an analysis of the backdoors in the Attacker’s Arsenal section.

The attackers exploited this vulnerability against the following trusted applications:

- Windows Search (vulnerable applications: searchindexer.exe /searchprotoclhost.exe)

- Fake DLL: msfte.dll (638b7b0536217c8923e856f4138d9caff7eb309d)

- Google Update (d30e8c7543adbc801d675068530b57d75cabb13f)

- Fake DLL: goopdate.dll (973b1ca8661be6651114edf29b10b31db4e218f7)

- Kaspersky’s Avpia (691686839681adb345728806889925dc4eddb74e)

- Fake DLL: product_info.dll (3cf4b44c9470fb5bd0c16996c4b2a338502a7517)

By exploiting legitimate software, the attackers bypassed application whitelisting and legitimate security software, allowing them to continue their operations without raising any suspicions.

DNS Tunneling as C2 channel -

In attempt to overcome network filtering solutions, the attackers implemented a stealthier C2 communication method, using “DNS Tunneling” – a method of C2 communicating and data exfiltration using the DNS protocol. To ensure that the DNS traffic would not be filtered, the attackers configured the backdoor to communicate with Google and OpenDNS DNS servers, since most organizations and security products will not filter traffic to those two major DNS services.

The screenshot below shows the traffic generated by the backdoor and demonstrates DNS Tunneling for C2 communication. As shown, while the destination IP is “8.8.8.8” – Google’s DNS server – the malicious domain is “hiding” inside the DNS packet:

Phase three: Novel MS Outlook backdoor and lateral movement spree

In the third phase of the operation, the attackers harvested credentials stored on the compromised machines and performed lateral movement and infected new machines. The attackers also introduced a very rare and stealthy technique to communicate with their servers and exfiltrate data using Microsoft Outlook.

Outlook macro backdoor

In a relentless attempt to remain undetected, the attackers devised a very stealthy C2 channel that is hard to detect since it leverages an email-based C2 channel. The attackers installed a backdoor macro in Microsoft Outlook that enabled them to execute commands, deploy their tools and steal valuable data from the compromised machines.

For a detailed analysis of the Outlook backdoor, please see the Attacker’s Arsenal section.

This technique works as follows:

- The malicious macro scans the victim’s Outlook inbox and looks for the strings “$$cpte” and “$$ecpte”.

- Then the macro will open a CMD shell that will execute whatever instruction / command is in between the strings.

- The macro deletes the message from inbox to ensure minimal risk of exposure.

- The macro searches for the special strings in the “Deleted Items” folder to find the attacker’s email address and sends the data back to the attackers via email.

- Lastly, the macro will delete any evidence of the emails received or sent by the attackers.

Credential dumping and lateral movement

The attackers used the famous Mimikatz credential dumping tool as their main tool to obtain credentials including user passwords, NTLM hashes and Kerberos tickets. Mimikatz is a very popular tool and is detected by most antivirus vendors and other security products. Therefore, the attackers used over 10 different customized Mimikatz payloads, which were obfuscated and packed in a way that allowed them to evade antivirus detection.

The following are examples of Mimikatz command line arguments detected during the attack:

The stolen credentials were used to infect more machines, leveraging Windows built-in tools as well as pass-the-ticket and pass-the-hash attacks.

Phase four: New arsenal and attempt to restore PowerShell infrastructure

After a four week lull and no apparent malicious activity, the attackers returned to the scene and introduced new and improved tools aimed at bypassing the security mitigations that were implemented by the company’s IT team. These tools and methods mainly allowed them to bypass the PowerShell execution restrictions and password dumping mitigations.

During that phase, Cybereason found a compromised server that was used as the main attacking machine, where the attackers stored their arsenal in a network share, which made it easier to spread their tools to other machines on the network. The attackers’ arsenal consisted:

- New variants of Denis and Goopy backdoors

- PowerShell Restriction Bypass Tool - Adapted from PSUnlock Github project.

- PowerShell Cobalt Strike Beacon - New payload + new C2 domain

- PowerShell Obfuscator - All the new PowerShell payloads are obfuscated using a publicly available script adapted from a Daniel Bohannon’s GitHub project.

- HookPasswordChange - Inspired by tools found on GitHub, this tool alerts the attackers if a password has been changed. Using this tool, the attackers could overcome a password reset. The attackers modified their tool.

- Customized Windows Credentials Dumper - A PowerShell password dumper that is based on a known password dumping tool, using PowerShell bypass and reflective loading. The attackers specifically used it to obtain Outlook passwords.

- Customized Outlook Credentials Dumper - Inspired by known Outlook credentials dumpers.

- Mimikatz - PowerShell and Binary versions, with multiple layers of obfuscation.

Please see the Attacker’s Arsenal section for detailed analysis of the tools.

An analysis of this arsenal shows that the attackers went out of their way to restore the PowerShell-based infrastructure, even though it had already been detected and shut down once. The attackers’ preference to use a fileless infrastructure specifically in conjunction with Cobalt Strike is very evident. This could suggest that the attackers preferred to use known tools that are more expendable rather than using their own custom-built tools, which were used as a last resort.

Conclusion

Operation Cobalt Kitty was a major cyber espionage APT that targeted a global corporation in Asia and was carried out by the OceanLotus Group. The analysis of this APT proves how determined and motivated the attackers were. They continuously changed techniques and upgraded their arsenal to remain under the radar. In fact, they never gave up, even when the attack was exposed and shut down by the defenders.

During the investigation of Operation Cobalt Kitty, Cybereason uncovered and analyzed new tools in the OceanLotus Group’s attack arsenal, such as:

- New backdoor (“Goopy”) using HTTP and DNS Tunneling for C2 communication.

- Undocumented backdoor that used Outlook for C2 communication and data exfiltration.

- Backdoors exploiting DLL sideloading attacks in legitimate applications from Microsoft, Google and Kaspersky.

- Three customized credential dumping tools, which are inspired by known tools.

In addition, Cybereason uncovered new variants of the “Denis” backdoor and managed to attribute the backdoor to the OceanLotus Group - a connection that had not been publicly reported before.

This report provides a rare deep dive into a sophisticated APT that was carried out by one of the most fascinating groups operating in Asia. The ability to closely monitor and detect the stages of an entire APT lifecycle - from initial infiltration to data exfiltration - is far from trivial.

The fact that most of the attackers’ tools were not detected by the antivirus software and other security products deployed in the company’s environment before Cybereason, is not surprising. The attackers obviously invested significant time and effort in keeping the operation undetected, striving to evade antivirus detection.

As the investigation progressed, some of the IOCs observed in Operation Cobalt Kitty started to emerge in the wild, and recently some were even reported being used in other campaigns. It is important to remember, however, that IOCs have a tendency to change over time. Therefore, understanding a threat actor’s behavioral patterns is essential in combatting modern and sophisticated APTs. The modus operandi and tools served as behavioral fingerprints also played an important role in tying Operation Cobalt Kitty to the OceanLotus Group.

Lastly, our research provides an important testimony to the capabilities and working methods of the OceanLotus Group. Operation Cobalt Kitty is unique in many ways, nonetheless, it is still just one link in the group’s ever-growing chain of APT campaigns. Orchestrating multiple APT campaigns in parallel and attacking a broad spectrum of targets takes an incredible amount of resources, time, manpower and motivation. This combination is likely to be more common among nation-state actors. While the are many rumours and speculations circulating in the InfoSec community, at the time of writing, there was no publicly available evidence that can confirm that the OceanLotus Group is a nation-state threat actor.

Until such evidence is made public, we will leave it to our readers to judge for themselves.

To be continued ... Meow.

Learn how to create a closed-loop security process to defend against this type of attack better.