Over the last several years, the Cybereason Nocturnus Team has been tracking different APT groups operating in the Middle East region, including two main sub-groups of the Hamas cyberwarfare division: Molerats and APT-C-23. Both groups are Arabic-speaking and politically-motivated that operate on behalf of Hamas, the Palestinian Islamic-fundamentalist movement and a terrorist organization that has controlled the Gaza strip since 2006.

While most of the previously reported APT-C-23 campaigns seemed to target Arabic-speaking individuals in the Middle East, Cybereason recently discovered a new elaborate campaign targeting Israeli individuals, among them, a group of high-profile targets working for sensitive defense, law enforcement, and emergency services organizations.

The campaign operators use sophisticated social engineering techniques, ultimately aimed to deliver previously undocumented backdoors for Windows and Android devices. The goal behind the attack was to extract sensitive information from the victims devices for espionage purposes.

Our investigation reveals that APT-C-23 has effectively upgraded its malware arsenal with new tools, dubbed Barb(ie) Downloader and BarbWire Backdoor, which are equipped with enhanced stealth and a focus on operational security. The new campaign that targets Israeli individuals seems to have a dedicated infrastructure that is almost completely separated from the known APT-C-23 infrastructure which is assessed to be more focused on Arabic-speaking targets.

Key Findings

- New Espionage Campaign Targeting Israelis: Cybereason discovered a new and elaborate campaign that targets Israeli individuals and officials. The campaign is characterized as an espionage campaign aiming to steal sensitive information from PCs and mobile devices belonging to a chosen target group of Israeli individuals working for law enforcement, military and emergency services.

- Attribution to APT-C-23: Based on our investigation and previous knowledge of the group, Cybereason assesses with moderate-high confidence that the group behind the new campaign is APT-C-23, an Arabic-speaking, politically motivated group believed to be operating on behalf of Hamas.

- Social Engineering as Primary Infection Vector: The attackers used fake Facebook profiles to trick specific individuals into downloading trojanized direct message applications for Android and PC, which granted them access to the victims’ devices.

- Upgraded Malware Arsenal: The new campaign consists of two previously undocumented malware, dubbed Barb(ie) Downloader and BarbWire Backdoor, both of which use an enhanced stealth mechanism to remain undetected. In addition, Cybereason observed an upgraded version of an Android implant dubbed VolatileVenom.

- APT-C-23 Stepping Up Their Game: Until recently, the group has been using known tools which served them for years, and were known for their relatively unsophisticated tools and techniques. The analysis of this recent campaign shows that the group has revamped their toolset and playbook.

Luring the Victims: A Wolf in a Beauty’s Clothing

To get to their targets, APT-C-23 has set up a network of fake Facebook profiles that are highly maintained and constantly interacting with many Israeli citizens. The social engineering tactic used in this campaign relies mostly on classic catfishing, using fake identities of attractive young women to engage with mostly male individuals to gain their trust.

These fake accounts have operated for months, and seem relatively authentic to the unsuspecting user. The operators seem to have invested considerable effort in “tending” these profiles, expanding their social network by joining popular Israeli groups, writing posts in Hebrew, and adding friends of the potential victims as friends:

In order to give the profiles an even more authentic appearance, the group uses the accounts to “like” various Facebook groups and pages that are well known to Israelis, such as Israelis news pages, Israeli politicians’ accounts and corporate pages:

Over time, the operators of the fake profiles were able to become “friends” with a broad spectrum of Israeli citizens, among them some high-profile targets that work for sensitive organizations including defense, law enforcement, emergency services and other government-related organizations:

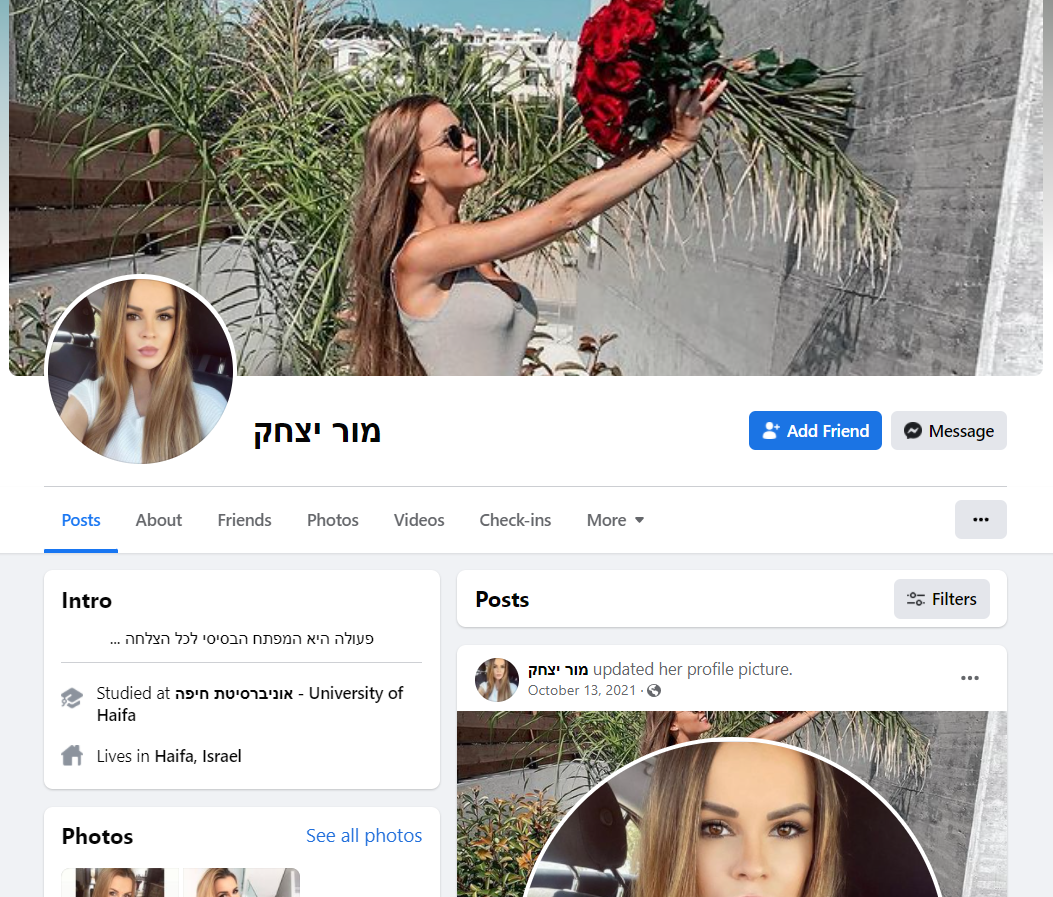

Another example of a fake profile used by APT-C-23 in this campaign, is the following:

From Chat to Infection

After gaining the victim’s trust, the operator of the fake account suggests migrating the conversation from Facebook over to WhatsApp. By doing so, the operator quickly obtains the target's mobile number. In many cases, the content of the chat revolves around sexual themes, and the operators often suggest to the victims that they should use a “safer” and more “discrete” means of communication, suggesting a designated app for Android.

In addition, they also entice the victims to open a .rar file containing a video that supposedly contains explicit sexual content. However, when the users open the video they are infected with malware.

The following diagram captures the flow of the infection:

- The VolatileVenom Malware: A supposedly “secure” and “confidential” Android messaging application.

- The Barb(ie) Downloader: A link to a site “hxxps://media-storage[.]site/09vy09JC053w15ik21Sw04” downloads a .rar file that contains a private video and the BarbWire Backdoor payload:

Stage One: Barb(ie) Downloader

Barb(ie) is a downloader component used by APT-C-23 to install the BarbWire backdoor. As mentioned above, in the infection phase the downloader is delivered alongside a video in a .rar file. The video is meant to distract the victim from the infection process that is happening in the background.

The downloader sample analyzed in this section is named “Windows Notifications.exe”. When first executed, Barb(ie) decrypts strings using a custom base64 algorithm that is also used in the BarbWire backdoor. Those decrypted strings are different Virtual Machine vendor names, WMI queries, command and control (C2), file and folders names which are used in different phases of the execution.

One way the malware uses those strings is in performing multiple checks, such as anti-vm and anti-analysis checks, in order to determine that “the coast is clear.” If the check fails, a custom pop-up message is displayed to the user and the malware terminates itself:

If the malware finds the target machine to be clean and it doesn’t detect any sandboxing or other analysis being performed on the targeted device, the malware will continue its execution and collect information about the machine, including username, computer name, date and time, running processes and OS version.

Later, the malware will attempt to create a connection to the embedded C2 server: fausto-barb[.]website. When creating the connection, the malware sends information about the victim machine that is composed of the data collected. In addition, it sends other information to the C2, like the OS version, downloader name and compilation month (“windowsNotification” + “092021”) as well as information on any installed Antivirus software running:

Barb(ie) will attempt to download the payload by using the following URI: “/api/sofy/pony”:

In addition, the downloader creates a file named “adbloker.dat” that stores the encrypted C2, copies itself to programdata and sets persistence via two scheduled tasks: “01” and “02”.

Interestingly, another Barb(ie) sample that was analyzed with a different name (“Windows Security.exe”) copies itself to appdata as well, but renames the executable to “Windows Notifications.exe” and sets the same persistence:

Looking at the metadata of Windows Notifications.exe, it appears that the author of the malware chooses a unique company name and product name that do not exist as part of Windows: “Windows Security Groups” as the company name, and “Windows Essential” as product name:

Once a successful connection has been established with the C2, Barb(ie) will download the payload, the BarbWire backdoor.

BarbWire Backdoor

Background and Capabilities

The backdoor component of APT-C-23’s operation is a very capable piece of malware, and it is obvious that a lot of effort was put into hiding its capabilities using a custom base64 algorithm. Its main goal is to fully compromise the victim machine, gaining access to their most sensitive data. The backdoor’s main capabilities include:

- Persistence

- OS Reconnaissance

- Data encryption

- Keylogging

- Screen capturing

- Audio recording

- Download additional malware

- Local/external drives and directory enumeration

- Steal specific file types and exfiltrate data

Variants

According to the timeline of this operation, there are at least three different variants of the BarbWire backdoor. In addition to the compilation timestamp, there is the “sekop” flag that is used as an identifier for a currently running campaign. It is worth mentioning that the variant that was allegedly compiled in December 2021, still carries the Sep 2021 identifier, perhaps meaning that the Sep 2021 campaign was still ongoing for at least two months:

|

MD5 Hash |

Variant |

Compilation timestamp |

“sekop” |

Similarity |

|

ff1c877db4d0b6a37f4ba5d7b4bd4b3b980eddef |

Early variant |

2021-07-04 07:39:15 UTC |

- |

62% with campaign variant |

|

ad9d280a97ee3a52314c84a6ec82ef25a005467d |

Analyzed Campaign |

2021-07-07 11:02:11 UTC |

"&sekop=072021_" |

90% with new variant |

|

4dcdb7095da34b3cef73ad721d27002c5f65f47b |

New variant |

2021-12-28 11:17:12 UTC |

“&sekop=092021_” |

59% with early |

Initial Execution and Victim Host Profiling

The BarbWire persistence techniques include the creation of a scheduled task and also the implementation of a known Process protection technique:

The malware handles two execution scenarios; If it is being executed from a location that is other than %programdata%, the malware copies itself to %programdata%\WMIhosts and creates a scheduled task:

According to a second execution scenario, where the file already operates from %appdata%, the malware starts collecting user information and gathering OS information including:

- PC name

- Username

- Process architecture

- Windows version

- Installed AV products using WMI

In order to hide the malware’s most sensitive strings, which can disclose its capabilities and communication patterns, it uses a custom-built base64 algorithm.

After successful C2 decryption, the BarbWire backdoor initiates a connectivity check using Google’s domain, and then connects with the C2:

It is worth noting that the URIs are in the same format as in the Barb(ie) downloader analyzed above, and other related files pivoted in this research:

Once the initial information is gathered on the victim’s OS and the connectivity check is completed, the BarbWire Backdoor finally initiates the connection with the C2 through a POST request:

The data that is sent in the POST request includes:

|

Parameter |

Data |

|

name |

A double layer encoded victim’s OS information |

|

sov |

Installed AV name |

|

sekop |

Campaign identifier and malware filename |

|

pos |

The victim’s OS and architecture |

Data Collection and Exfiltration

The BarbWire backdoor can steal a wide range of file types, depending on the instructions it receives from its operators. It specifically looks for certain file extensions such as PDF files, Office documents, archives, videos, and images.

In addition to the local drives found on the host, it also looks for external media such as a CD-Rom drive. Searching for such an old media format, together with the file extensions of interests, could suggest a focus on targets that tend to use more “physical” formats to transfer and secure data, such as military, law enforcement, and healthcare:

BarbWire stores the data it collects from the host on special folders it creates under %programdata%\Settings where it stores the collected data from the machine. Each stolen “type” (i.e. keylogged data,screen capture data etc.) has its own resource “code name” in the C2, appended to the previously generated user id:

Below is a table summarizing each folder and its main role:

|

Folder Name |

Role |

|

activationData, backup, recoveryFile |

Staging data in a RAR archive and exfiltration, download additional payloads, volumes and documents of interest enumeration |

|

logFile |

Audio recording |

|

scanLog |

Keylogger log file |

|

updateStatus |

Screenshots files |

Once the data is being staged and exfiltrated, the data is archived in a .rar file and sent to the C2 to a designated URI:

As detailed in the beginning of the analysis, the backdoor also has keylogging and screen capturing data-stealing capabilities. Both are being stored in an interesting way, applying unrelated extensions to the files containing the stolen data. This is perhaps another stealth mechanism, or just a way for the attacker to distinguish between the different stolen data types:

A screenshot taken by the malware and saved with an .iso extension

VolatileVenom Android Implant Analysis

VolatileVenom is one of APT-C-23’s arsenal of Android malware. The attackers lure the victims into installing the VolatileVenom under the pretext that the suggested app is more “secure” and “discrete.” Based on our investigation, it seems that VolatileVenom has been operationalized and integrated into the group's arsenal since at least April of 2020, and disguises itself using icons and names of chat applications:

An example of a fake messaging app used in this campaign, is an Android app named “Wink Chat”:

After the user attempts to sign up for the application, an error message pops up and indicates the app will be uninstalled:

However, in reality the application keeps running in the background, and if the Android version of the device is lower than 10, the application icon is hidden. If the Android version is higher than Android 10, the application icon is then replaced with the icon of Google Play installer. The attackers have the option to change the application icon to Google Chrome or Google Maps as well.

Capabilities

VolatileVenom has a rich set of espionage capabilities, which enable attackers to extract a lot of data from their victims.

The main espionage capabilities are the following:

- Steal SMS messages

- Read contact list information

- Use the device camera to take photos

- Steal files with the following extensions: pdf, doc, docs, ppt, pptx, xls, xlsx, txt, text

- Steal images with the following extensions: jpg, jpeg, png

- Record audio

- Use Phishing to steal credentials to popular apps such as Facebook and Twitter

- Discard system notifications

- Get installed applications

- Restart Wi-Fi

- Record calls / WhatsApp calls

- Extract call logs

- Download files to the infected device

- Take screenshots

- Read notifications of the following apps: WhatsApp, Facebook, Telegram, Instagram, Skype, IMO, Viber

- Discards any notifications raised by the system

C2 Communication

VolatileVenom uses HTTPS and Firebase Cloud Messaging (FCM) for C2 communication. The application appears to have two methods to retrieve the C2 domain:

First the malware decrypts a hard coded encrypted domain which is encrypted and encoded with AES and Base64. The encrypted domain is retrieved from a .so (shared object) file. The app loads the .so file (named “liboxygen.so” in the analyzed sample) , and executes a function (named “do932()” in the analyzed sample) that returns the encrypted domain:

Next, the encrypted domain is decoded and decrypted. In the analyzed sample, the encrypted domain is “https://sites.google[.]com/view/linda-lester/lockhart”:

To retrieve the final C2 domain, the malware connects to the decrypted domain and reads the title of the website (ex: FRANCES THOMAS COM) and builds the final C2 domain from that: frances-thomas[.]com:

The second method the malware retrieves the C2 domain is via SMS messages. In case the attackers wish to update the C2 domain, they may send an SMS message containing a new C2 domain to the infected device. The malware intercepts every SMS message, and if a message arrives from the attackers, the malware will extract the new C2 domain to be used:

Conclusion

In this report, the Cybereason Nocturnus Team investigated an active espionage campaign that victimizes Israeli citizens, among them high profile targets, for espionage purposes. The campaign featured a classic social engineering tactic known as catfishing, where the group used sexual content in order to lure their victims, mostly Israeli men, into downloading malware.

Cybereason assesses with moderate-high confidence that APT-C-23, a politically-motivated APT group that operates on behalf of Hamas, is behind the campaign detailed in this report. While the APT-C-23 operations against Arab-speaking targets (mostly Palestinians) are still taking place, this newly identified campaign specifically targets Israelis and shows unique characteristics that distinguish it from other campaigns. The attackers use a completely new infrastructure that is distinct from the known infrastructure used to target Palestinians and other Arabic-speakers. In addition, all three malware in use were also specifically designed to be used against Israeli targets, and were not observed being used against other targets.

The Cybereason investigation found that some victims were infected with both PC and Android malware dubbed Barb(ie) Downloader, BarbWire Backdoor, and VolatileVenom. This “tight grip” on their targets attests to how important and sensitive this campaign was for the threat actors.

Lastly, this campaign shows a considerable step-up in APT-C-23 capabilities, with upgraded stealth, more sophisticated malware, and perfection of their social engineering techniques which involve offensive HUMINT capabilities using a very active and well-groomed network of fake Facebook accounts that have been proven quite effective for the group.

Cybereason contacted Facebook and reported the fake accounts.

Indicators of Compromise

LOOKING FOR THE IOCs? CLICK ON THE CHATBOT DISPLAYED IN LOWER-RIGHT OF YOUR SCREEN FOR ACCESS OR CLICK HERE.

MITRE ATT&CK BREAKDOWN

|

Execution |

Reconnaissance |

Persistence |

Defense Evasion |

Credential Access |

Discovery |

Collection |

Command and Control |

Exfiltration |

MITRE ATT&CK BREAKDOWN: MOBILE

|

Initial Access |

Execution |

Persistence |

Privilege Escalation |

Defense Evasion |

Credential Access |

Discovery |

Collection |

Command and Control |

Exfiltration |