Research by: Cybereason Nocturnus Team

Background

Over the last several months, the Cybereason Nocturnus team has been tracking recent espionage campaigns targeting the Middle East. These campaigns are specifically directed at entities and individuals in the Palestinian territories. This investigation shows multiple similarities to previous attacks attributed to a group called MoleRATs (aka The Gaza Cybergang), an Arabic-speaking, politically motivated group that has operated in the Middle East since 2012.

In our analysis, we distinguish between two separate campaigns happening simultaneously. These campaigns differ in tools, server infrastructure, and nuances in decoy content and intended targets.

- The Spark Campaign: This campaign uses social engineering to infect victims, mainly from the Palestinian territories, with the Spark backdoor. This backdoor first emerged in January 2019 and has been continuously active since then. The campaign’s lure content revolves around recent geopolitical events, espeically the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the assassination of Qasem Soleimani, and the ongoing conflict between Hamas and Fatah Palestinian movements.

- The Pierogi Campaign: This campaign uses social engineering attacks to infect victims with a new, undocumented backdoor dubbed Pierogi. This backdoor first emerged in December 2019, and was discovered by Cybereason. In this campaign, the attackers use different TTPs and decoy documents reminiscent of previous campaigns by MoleRATs involving the Micropsia and Kaperagent malware.

In part one of this research, we analyze the Spark campaign. This campaign is named after a rare backdoor used by the MoleRATs Group, dubbed Spark by Cybereason and previously reported by 360’s blog.

For a detailed report on the Pierogi campaign, please see part 2 of this research.

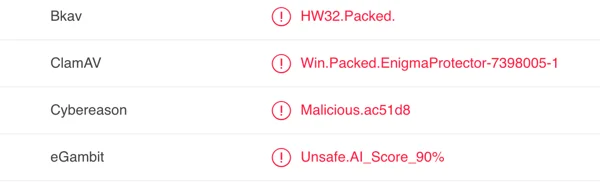

The creators of the Spark backdoor use several techniques to evade detection and stay under the radar. They pack the malware with a powerful commercial tool called Enigma Packer and implement language checks to ensure the victims are Arabic speaking. This minimizes the risk of detection and infection of unwanted victims.

Key Points

- Cyber Espionage in the Middle East: The Cybereason Nocturnus team has discovered several recent, targeted attacks in the Middle East. These attacks deliver the Spark and Pierogi backdoors for politically-driven cyber espionage operations.

- Targeting Palestinians: The campaigns seems to target Palestinian individuals and entities, likely related to the Palestinian government.

- Politically-motivated APT: Cybereason suspects that the objective of the threat actor is to obtain sensitive information from the victims and leverage it for political purposes.

- Lured Into Deploying a Backdoor: The attackers use specially crafted lure content to trick targets into opening malicious files that infect the victim’s machine with a backdoor. The lure content in the malicious files relates to political affairs in the Middle East, with specific references to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, tension between Hamas and Fatah, and other political entities in the region.

- Perpetrated by an Arabic-Speaking APT Group: The modus-operandi of the attackers in conjunction with the social engineering tactics and decoy content seem aligned with previous attacks carried out by the Arabic-speaking APT group MoleRATs (aka Gaza Cybergang). This group has been operating in the Middle East since 2012.

For a synopsis of this research, check out the Molerats & Pierogis Threat Alert.

Table of Contents

Suspected Threat Actor Description

These attacks show significant similarities to previously documented attacks attributed to the Arabic-speaking threat actor, commonly referred to as the MoleRATs group (aka, The Gaza Cybergang, Moonlight, DustySky, Gaza Hacker Team). This group, which has been attributed by various security teams, is believed to be comprised of three subgroups:

- Gaza Cybergang Group 1, also dubbed MoleRATs: MoleRATs has been active since at least 2012. This Arabic-speaking group uses spear phishing attacks to infect target machines in the Middle East and North Africa with various Remote Access Trojans (RATs). As MoleRATs most prominently targets Palestinian territories, its spear phishing attacks often use attached malicious documents on topical Palestinian Authority-related issues to lure their victims. The group uses a mix of tools and malware, some developed by the group and others that are more generic tools.

- Gaza Cybergang Group 2, also dubbed Desert Falcons, APT-C-23, Arid Viper. This second group is an Arabic-speaking group that mainly targets the Middle East and North Africa, with a few targets in European and Asian countries as well. The group is known for their advanced attacks that leverage custom-built Windows malware (Kasperagent, Micropsia) as well as Android malware (Vamp, GnatSpy).

- Gaza Cybergang Group 3: This group is believed to be behind Operation Parliament. It is considered to be the most advanced group of the three, and is focused on high-profile targets in the Middle East, North America, Europe and Asia. The group is reported to have previously attacked government institutions, parliaments, senates, diplomatic functions, and even Olympic and other sports bodies.

A Note on Attribution

It is important to remember there are many threat actors operating in the Middle East, and often there are overlaps in TTPs, tools, motivation, and victimology. There have been cases in the past where a threat actor attempted to mimic another to thwart attribution efforts, and as such, attribution should rarely be taken as is, but instead with a grain of salt and critical thinking.

Infection Vector - Social Engineering using Targeted Content

Themes of the Content Used to Lure Targets

In this attack, the targets are lured to open a document or a link attached to an email. There have been cases in the past where victims also downloaded malicious content from fake news websites. The names of the files and their content play a major part in luring victims to open them, as they usually relate to current topics pertaining to Hamas, the Palestinian National Authority, or other recent events in the Middle East. The lure documents analyzed by Cybereason in this attack concentrate on the following themes:

- The Conflict between Hamas and Fatah: The historical rivalry between the Hamas and Fatah has resulted in many open battles between the two entities. Since 2006, Hamas has controlled the Gaza strip and Fatah has controlled the West Bank.

- Matters pertaining to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Some of the documents in this campaign reference different aspects of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the efforts for ceasefire and peace processes between the Israelis and the Palestinians, including the latest peace plan made by President Donald Trump and Senior Advisor to the President of the United States Jared Kushner.

- Vigilance Following Soleimani’s Assassination: One of the lure documents mentions sources in Lebanon that report a state of alert and vigilance amongst Iranian, Syrian, and Lebasense militias following Soleimani’s assassination.

- Tensions Between Hamas and the Egyptian Government: Egypt plays a major role as a mediator in the Israeli-Palestinian confict and has brokered several ceasefire deals and other negotiations in the past. Changes to Egypt’s internal political climate are known to have affected Egyptian government relations with Hamas over the years. It was recently reported that Ismail Haniyeh, the head of Hamas’ political Bureau, had a falling-out with the Egyptian government over his visit to Tehran to participate in General Qasem Soleimani’s funeral, following Soleimani’s assassination.

|

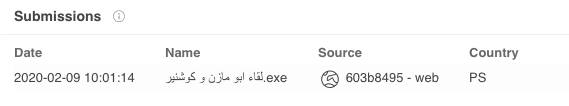

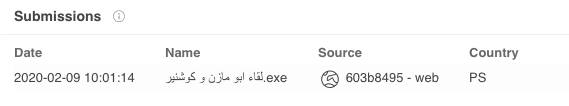

Spark Backdoor dropper named “Abu-Mazen and Kushner’s meeting” uploaded to VirusTotal from the Palestinian territories.

|

File Name

|

SHA-256

|

|

لقاء ابو مازن و كوشنير.exe

Translation: Meeting between Abu-Mazen and Kushner

|

01887df1febdf6fdf85e870e8d87f4397a4854ffedeaffd2f8d21310306e50b0

|

|

محضر اجتماع قيادةالاجهزة الامنية في غزة من اجل افشال انطلاقة فتح.exe

Translation: Minutes of the meeting of the leadership of the security services in Gaza in order to thwart the anniversary of Fatah.exe

|

2268101c32989e7cfcb8b2ef47163f741850e7619edf0c0e8f365cfceb1b1e82

|

|

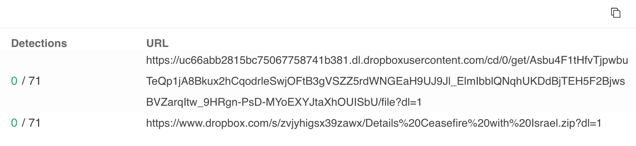

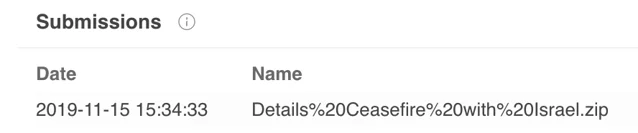

Details%20Ceasfire%20with%Israel.zip

|

31b08c139b6fc3bdde0734d1b2c609550a03ca97ec941eaf24224bb449e17e26

|

|

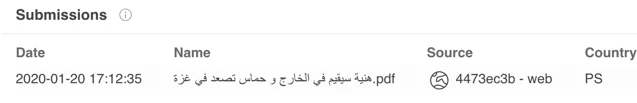

هنية سيقيم في الخارج و حماس تصعد في غزة.pdf

Translation: Haniyeh will remain abroad and Hamas steps up in Gaza.pdf

|

5b476e05aacea9edc14f7e4bab1b724ef54915f30c39ac87503ed395feae611e

|

|

تقرير معلومات فوري.exe

Translation: Urgent Information Report.exe

|

6e896099a3ceb563f43f49a255672cfd14d88799f29617aa362ecd2128446a47

|

Table that summarizes files observed in the Spark campaign.

In the Spark campaign, the lure documents and links point to one of two file sharing websites, Egnyte or Dropbox. The target is encouraged to download an archive file in a rar or zip format that contains an executable file masquerading as a Microsoft Word document.

The following file was downloaded from DropBox:

Malicious archive hosted on Dropbox.

Malicious archive with a name meant to lure targets.

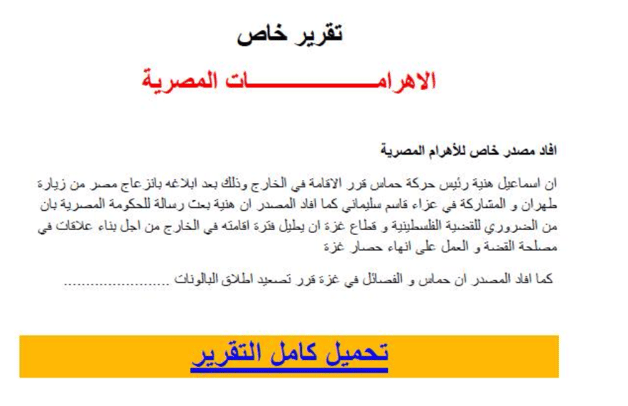

Example 1: Social Engineering using a PDF Document

One example of a lure document used in the Spark campaign is a PDF file that is used to deliver the Spark backdoor to the victim. The document includes a special report allegedly quoted from the Egyptian newspaper Al-Ahram. This document reports that Ismail Hanieyh, the political leader of Hamas, had notified the Egyptian government that he will remain abroad after his visit to Tehran to take part in Soleimani’s funeral, which sparked tension with the Egyptian authorities.

|

File Name

|

SHA-256

|

|

هنية سيقيم في الخارج و حماس تصعد في غزة.pdf

Translation: Haniyeh will remain abroad and Hamas rises in Gaza.pdf

|

5b476e05aacea9edc14f7e4bab1b724ef54915f30c39ac87503ed395feae611e

|

The document was submitted to VirusTotal on the 20/01/2020 from the Palestinian territories:

Document uploaded to VirusTotal on 20/01/2020 from the Palestinian territories.

Phishing document luring the readers to click on a malicious link.

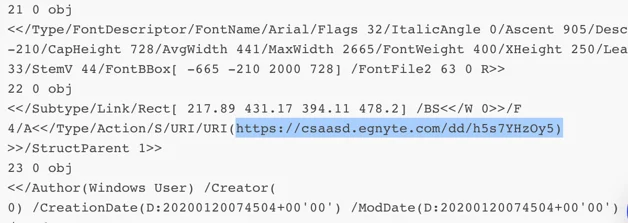

The target is encouraged to click on the link to read the entire article. However, the document does not link to the Egyptian Newspaper website, but instead to a file sharing website called Egnyte. It prompts the user to download a file that supposedly contains the full article.

Link embedded in the PDF document: hxxps://csaasd.egnyte[.]com/dd/h5s7YHzOy5

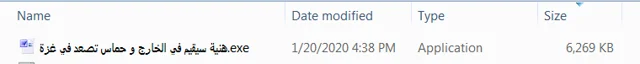

The downloaded file is an archive file (.r23), that contains a Windows executable file with the same name as the PDF and with a fake Microsoft Word icon.

|

SHA-256

|

File Name

|

|

e8d73a94d8ff18c7791bf4547bc4ee2d3f62082c594d3c3cf7d640f7bbd15614

|

هنية سيقيم في الخارج و حماس تصعد في غزة.r23

(Hanieh will remain abroad and Hamas steps up in Gaza.r23)

|

|

7bb719f1c64d627ecb1f13c97dc050a7bb1441497f26578f7b2a9302adbbb128

|

هنية سيقيم في الخارج و حماس تصعد في غزة.exe

(Hanieh will remain abroad and Hamas steps up in Gaza.exe)

|

Spark backdoor dropper file masquerading as Word document using a fake icon.

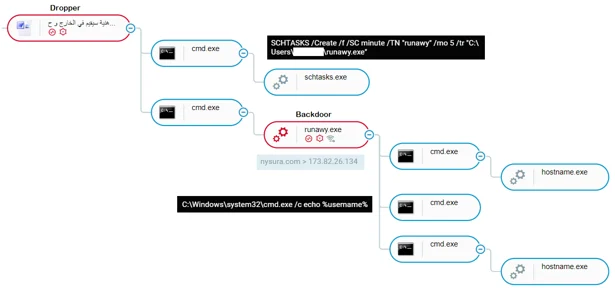

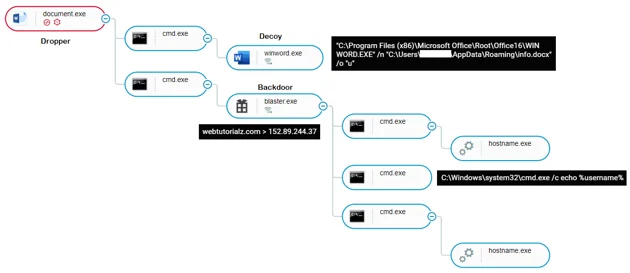

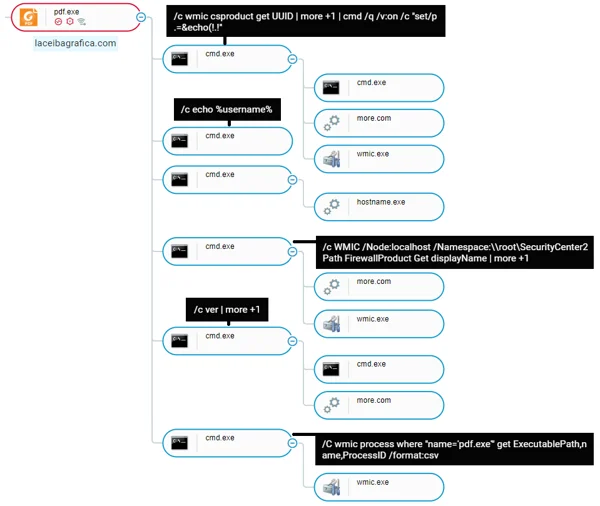

When the victim double clicks on the executable file, it unpacks and installs the Spark backdoor, as shown in the attack tree screenshot below.

Installation process of the Spark backdoor, as shown in Cybereason’s attack tree.

Backdoor Installation: Autoit Dropper

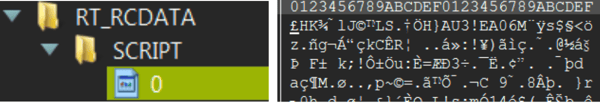

The extracted executable file contains a compiled Autoit script, which can be seen in the RT_RCDATA section of the file.

Autoit indications found in the binary resources of the dropper (SHA-256: 7bb719f1c64d627ecb1f13c97dc050a7bb1441497f26578f7b2a9302adbbb128).

The decompiled code shows the decryption routine that unpacks the embedded Spark backdoor.

Excerpt from the decompiled Autoit script where it is unpacking the Spark backdoor.

Once the file is unpacked, the backdoor is dropped in two different locations on the infected operating system:

- C:\Users\user\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\runawy.exe

- C:\Users\user\runawy.exe

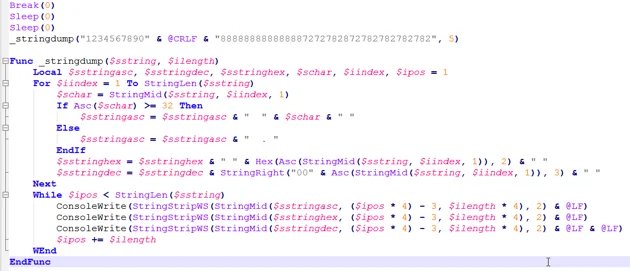

In addition, the Autoit code also creates the following scheduled task for persistence:

- SCHTASKS /Create /f /SC minute /TN runawy /mo 5 /tr C:\Users\<USER>\runawy.exe

Excerpt from the decompiled Autoit script where it installs the backdoor and creates persistence.

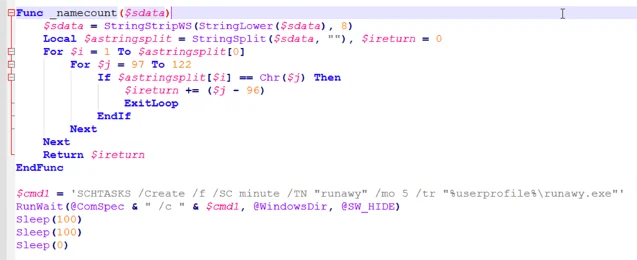

Example 2: Dropper with a Decoy Document

During our investigation, we found the following executable file.

|

File name

|

SHA-256

|

|

تقرير معلومات فوري.exe

(Urgent Information Report.exe)

|

6e896099a3ceb563f43f49a255672cfd14d88799f29617aa362ecd2128446a47

|

The executable has a Microsoft Word icon to trick victims into believing they are opening a Word document.

Spark backdoor dropper file masquerading as Word document using a fake icon

Once the user double-clicks on the executable file, the dropper drops a Word document in %AppData% and displays the following decoy document to the victim, while the dropper runs in the background and installs the backdoor.

|

Decoy Document Name and Path

|

SHA-256

|

|

%appdata%\info.docx

|

2c50eedc260c82dc176447aa4116ad37112864f4e1e3e95c4817499d9f18a90d

|

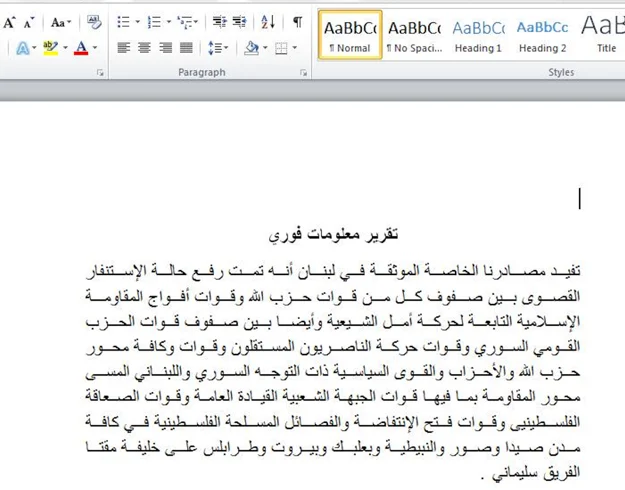

The decoy document presents to the user titled “Urgent Information Report” in Arabic.

The dropper drops the Spark backdoor binary and a shortcut file used to initiate persistence in the following locations.

|

File name

|

SHA-256

|

|

C:\Users\user\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\Blaster.lnk

|

4254dc8c368cbc36c8a11035dcd0f4b05d587807fa9194d58f0ba411bfd65842

|

|

C:\Users\user\AppData\Roaming\Blaster.exe

|

cf32479ed30ae959c4ec8a286bb039425d174062b26054c80572b4625646c551

|

Cybereason UI: The attack tree displaying the Spark backdoor infection chain.

Spark Backdoor Analysis

The Spark payload is a custom backdoor likely developed by the MoleRATs group. In addition to known generic malware (such as: njRAT, Poison Ivy, XtremeRAT), the MoleRATs group has been known to develop its own custom tools such as DustySky, the MoleRAT Loader and Scote. We believe this backdoor is relatively new and seems to have appeared starting in the beginning of 2019.

The name Spark is derived from the PDB path left in a few of the backdoor binaries:

- W:\Visual Studio 2017\Spark4.2\Release\Spark4.2.pdb

The Spark backdoor allows the attackers to:

- Collect information about the infected machine.

- Encrypt the collected data and send it to the attackers over the HTTP protocol.

- Download additional payloads.

- Log keystrokes.

- Record audio using the computer’s microphone.

- Execute commands on the infected machine.

The creators of the Spark backdoor use a few techniques that are intended to keep the backdoor under-the-radar, including:

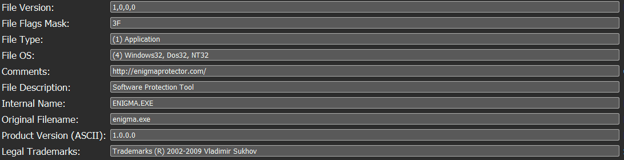

- Packing the payloads with the Enigma packer.

- Checking for antivirus and other security products using WMI.

- Validating Arabic keyboard and language settings on the infected machine.

Enigma Packer

All the the payloads observed by Cybereason in this campaign were packed by a powerful yet commercial packer called Enigma Packer. The MoleRATs group have been known to use this packer in previous attacks.

Enigma packer artifacts in file metadata (SHA-256: b08b8fddb9dd940a8ab91c9cb29db9bb611a5c533c9489fb99e36c43b4df1eca).

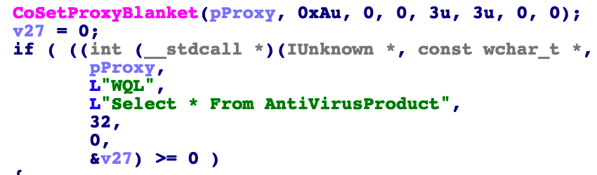

Checking for Security Products

One common evasive mechanism used by the Spark backdoor is its ability to check for installed security products using WMI queries (WQL). If certain security products are installed, the backdoor does not carry out its malicious activity.

- SELECT * FROM AntiVirusProduct

- SELECT * FROM FirewallProduct

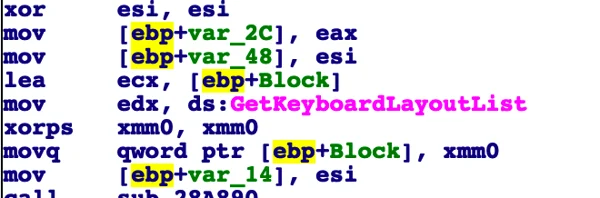

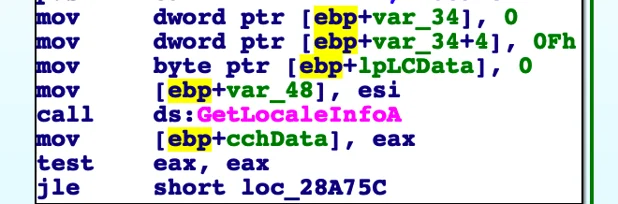

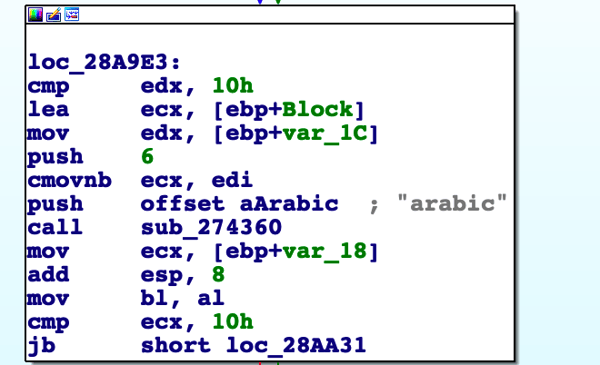

Checking for the Arabic Language

Another evasive mechanism used by the backdoor is how it checks whether an Arabic keyboard and Arabic language settings are used on the infected machine. If Arabic keyboard and language settings are not found on the machine, the backdoor will not carry out its malicious activity. This check serves two purposes:

- It minimizes the risk of overexposure by specifically targeting Arabic speakers.

- It can thwart detection by automated analysis engines and sandbox solutions.

Enumerating installed keyboards on the infected machine.

Obtaining locale information from the infected machine.

Comparing the results of the language checks with the word Arabic.

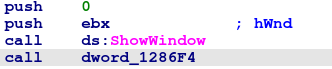

Using a Hidden Window

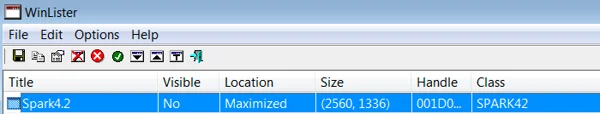

After unpacking itself, the Spark backdoor creates a hidden window where most of the malicious activity is handled.

Creation of the hidden window, using 0 value for the ShowWindow function to hide the window.

This behavior can be detected using a tool called WinLister, which enumerates hidden windows. The name of the window is Spark4.2.

C2 Communication

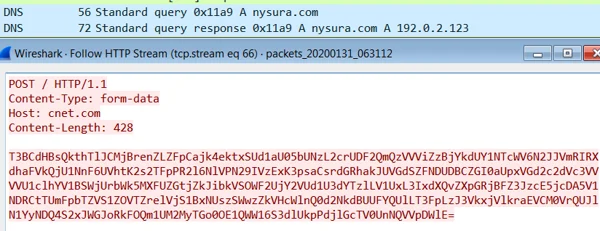

The Spark backdoor communicates with the C2 servers over the HTTP protocol. The data is first encrypted and then encoded with Base64. In this instance, the backdoor posts the data to the domain Nysura[.]com (For more domains, please see the IOC section of this research).

It is interesting to see that the HTTP POST host header refers to a legitimate domain cnet.com, however, in acutality, the data is sent to nysura[.]com, as can be seen in the traffic screenshot below.

The Spark backdoor sends data to the C2 server.

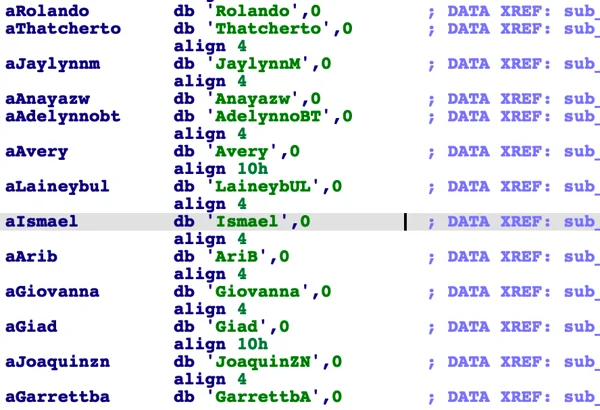

The data sent to the C2 follows a structured pattern that uses a predefined keywords array, where each keyword is mapped to a certain subroutine. The keywords are comprised of the names of individuals. They are mostly Western names, but there were some Arabic names in a few of the samples.

Keywords comprised of names used by the backdoor.

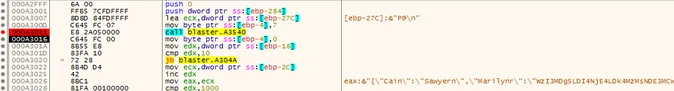

Prior to sending the data to the server, the data is encrypted and staged in an array like this:

[27089,28618,9833,4170,25722,19977,2369,21426,3435,7442,30146,21719,16140,16280,16688,22550,19867,194,3298]

The data is then encoded with Base64:

"WzI3MDg5LDI4NjE4LDk4MzMsNDE3MCwyNTcyMiwxOTk3NywyMzY5LDIxNDI2LDM0MzUsNzQ0MiwzMDE0NiwyMTcxOSwxNjE0MCwxNjI4MCwxNjY4OCwyMjU1MCwxOTg2NywxOTQsMzI5OF0="

The Base64-encoded data is inserted into the following json object, which contains the individual names.

json object containing the Base64-encoded data.

Lastly, the entire json object is encoded with Base64 and undergoes another stage of encryption, and then sent to the server:

ZjRTc1dTTU9nVW5FaXM3bGgvbU90MTlVMHFkb1c5SFFuRXhhSVR5YytIQkZremk3bk5wY21BUEZRYitJenA1cnlJY1lxREJJZ1RrL0N4UzZWcVVQM0pTUWFISlhKWG8wN1BxWE1hYThHSUdEVnBFakYrNlp1bXBvdUZMRFNYQVhxYk9tSElWYTFOTlpJK0hFVVBmTG9CQUV3VCtqQ2FCVUE1aHQ2SzllSHREMUpOdkdBUXZ3TWgyLzhtVHpha2I0TE81ZlpURTQyUmVjdFY1M0ZpemlRR1FLL1gzNE9mcU0zR0JqQ1ZnN1hCSmFGaC94RHBDMkNBRmZaSTVoVlhsaTBtQW5SR3N5QzVRY2lMNkpZVFJuRTQrUzBjdjU4SjY4ejRCL2FNbW9IakRheHdQd1RPUElkOHNDbDRVbmp2ZDM0ZVZlZTB1QVA0UHo0YllyVHRMZVRnPT0="

Using names as keywords is an identical technique to that of the data structure logic previously documented by 360’s blog post. This post discusses an earlier variant of the backdoor attributed to the MoleRATs group. Using other individuals names for C2 communication has also been done by the two other Gaza Cybergang groups:

- Gaza Cybergang Group 2 with the Micropsia backdoor: In this instance, the C2 communication implemented by the Micropsia backdoor also used specific names for different C2 commands.

- Gaza Cybergang Group 3 in Operation Parliament: In this instance, the malware also used people’s names for C2 communication to send and receive commands from the server. Based on the similarity of the naming convention and data format, we believe the Spark backdoor could be an evolution of the backdoor mentioned in Operation Parliament, or at least inspired by the malware.

Conclusion

The Spark campaign detailed in this blog demonstrates how the tense geopolitical climate in the Middle East is used by threat actors to lure victims and infect them with the Spark backdoor for cyber espionage purposes.

The names of the files and decoy content seem to be carefully crafted, often referencing controversial and topical political issues. Cybereason estimates that the files are specifically meant to lure and appeal to victims from the Middle East, especially towards individuals and entities in the Palestinian territories likely related to the Palestinian government or the Fatah movement.

The techniques, tools, and procedures used in this campaign bear great resemblance to previous attacks attributed to the MoleRATs Group (aka Gaza Cybergang Group), an Arabic-speaking, politically motivated group that has operated in the Middle East since 2012.

Our research demonstrates the efforts used by attackers to reduce the risk of detection of the Spark backdoor by various security products. The backdoor checks for the existence of antivirus and firewall products before it initiates its malicious activity. Importantly, the backdoor simply will not reveal its malicious nature unless Arabic language keyboard and settings are found on the infected machine. This shows how the attackers use this backdoor in a surgical way to exclusively attack specific targets.

In addition, analysis of these backdoor delivery methods also highlights a trend by many threat actors where they use legitimate storage platforms to deliver the initial stages of the attack. By storing malicious content on trusted platforms like DropBox, attackers reduce the risk of detection by certain security solutions that are gaining popularity, like email filters.

Cybereason Detection, Visibility, and Prevention

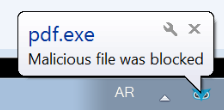

Cybereason prevents and detects the attacks mentioned in this research.

Cybereason UI: The attack tree showing the installation of the Spark backdoor.

Cybereason’s Next-generation Antivirus can detect and prevent the Spark backdoor.

(SHA-256: 5139a334d5629c598325787fc43a2924d38d3c005bffd93afb7258a4a9a8d8b3)

The file (pdf.exe) was automatically blocked by NGAV.

Cybereason agent blocks the execution of the Spark Backdoor.

Indicators of Compromise

Click here to download the MoleRATs IOCs (PDF)

MITRE ATT&CK BREAKDOWN