Cybereason has discovered another member in the xxmm family of backdoors---ShadowWali. Like the Wali backdoor, ShadowWali also targets Japanese businesses and was built by the xxmm malware toolkit. In fact, the same author can be attributed to both backdoors. ShadowWali is likely an earlier version of Wali, making it Wali's "older brother."

Check out the ServHelper backdoor for more research on backdoors.

In this blog, we'll review the xxmm backdoor family and show the similarities between Wali and ShadowWali. In addition, we will provide new insights regarding the backdoor's post-infection phases.

The XXMM backdoor family

Wali is a backdoor used for targeted attacks. It gathers information about the compromised machines and their networks, in addition to stealing sensitive information and credentials. Wali’s operators use this information to move laterally in an organization and compromise more machines. There are many similarities between the Wali and ShadowWali:

- Same author: PDB paths found in the analyzed binaries indicate that both Wali and ShadowWali stem from the same author: user 123. The author likely built the backdoors from three different Visual Studio projects (xxmm2, xxmm3, ShadowWalker):

- C:\Users\123\documents\visual studio 2010\Projects\xxmm2\Release\test2.pdb

- C:\Users\123\documents\visual studio 2010\Projects\xxmm2\x64\Release\BypassUacDll.pdb

- C:\Users\123\Documents\Visual Studio 2010\Projects\xxmm2\Release\loadSetup.pdb

- C:\Users\123\Desktop\xxmm3\x64\Release\ReflectivLoader.pdb

- C:\Users\123\Documents\Visual Studio 2010\Projects\shadowWalker\x64\Release\BypassUacDll.pdb

Evidence suggests that Wali’s author has been developing these backdoors and possibly other malware since 2015.

Same builder: Wali and its sibling backdoor were built using the xxmm builder. (see the section The xxmm builder dissected)

Similar tactics, techniques and procedures

Large inflated executables: Both backdoors have unusually large inflated binaries (ranging between 50,000KB and 200,000KB). This is a tactic used to evade inspection by traditional antivirus software and other security products.

Process injection: Most samples were observed injecting malicious payloads to Internet Explorer. However, ShadowWali was also observed injecting to LSASS.exe process and to explorer.exe.

A main differentiator between Wali and its sibling backdoor is that Wali’s loader comes with both a 32-bit and 64-bit payload, while ShadowWali tends to deliver 32-bit payloads. Another key difference is the style of the process injection technique. Both backdoors use different process injection techniques.

- C2 Infrastructure---Legitimate and fake Japanese websites

- Many of the C&C domains and IPs lead to legitimate Japanese and/or Japan-related websites that had been compromised. Additionally, some of the C&C domains that were observed are suspected to be fake websites that mimic the sites of legitimate Japanese businesses.

- The compromised sites are almost exclusively written in PHP. This has to do with one of the features of the xxmm builder, which supports communication over a PHP Tunnel.

- Many of the compromised sites are hosted by one of Japan’s largest hosting companies: the GMO Internet Group, which has allegedly fallen victim to cyberattacks in the past.

Wali backdoor

The Wali backdoor emerged in Japan in early 2016. It’s dubbed Wali because of the indicative strings found inside its binaries, as seen in the screenshot of the strings from a decrypted Wali binary (SHA-1: 3603163413A8E4E03758C9FB7673E1866FF29CB5):

Wali’s Process Injection

One of the consistent characteristics of Wali is the injection of the malicious payloads (either 32-bit or 64-bit) into a host process. As seen in our analysis of the xxmm builder (See the section The xxmm builder dissected), the default host process of choice is Internet Explorer (iexplore.exe). The screenshot below, taken from a real attack attempt on one of our Japanese customers, shows Wali’s loader (srvhost.exe) injecting code into Internet Explorer. Let’s have a look at the injection detected by Cybereason:

Srvhost.exe loader injecting to Internet Explorer. Visual taken from the Cybereason Platform.

Wali injection routine combines implementations of "Reflective DLL injection" along with another injection technique. Wali’s author clearly borrowed code from Stephen Fewer’s famous ReflectiveDLLInjection project found on Github.

Stephen Fewer’s Reflective DLL Injection code on Github:

Excerpt taken from Wali's process injection routine:

However, a few alterations were made to the code to accommodate the 32-bit and 64-bit payload delivery. Following is a simplified flow of the injection routine, with main differences marked in red:

CreateProcessA → OpenProcess → VirtualAllocEx → WriteProcessMemory → GetVersionEx → CreateRemoteThread/NtCreateThreadEx

Step 1: Create iexplore.exe in suspended mode

Since Wali’s author chose to inject to Internet Explorer---a host process that doesn’t necessarily run all the time---Wali first needs to make sure the browser runs, and launches it in a suspended mode (creation flag = CREATE_SUSPENDED):

Step 2: Allocating two RWX regions in target process and injecting the payloads

Next, the loader will allocate two RWX regions in the target process and write the 32-bit and 64-bit payload respectively.

It's interesting to notice the size of the actual injected payloads---At 120KB to 144KB, the actual payloads are tiny compared to the 100MB to 200MB loader that’s inflated with junk code.

Step 3: Determining OS version and executing a remote thread in target process

During the final step of the injection routine, Wali's loader determines the OS version of the compromised host. If the value of dwMajorVersion is lower than 6 (older than Vista), the loader will call CreateRemoteThread to execute the injected payload:

Otherwise, it will use the rare and undocumented NtCreateThreadEX API to execute the injected code. The motivation behind the version check is most likely to overcome Windows “Session Separation” mitigation introduced in Windows Vista:

C2 communication

Wali uses GET requests over HTTP port 80 to communicate with its C&C servers, which are mostly compromised websites. Most samples have a set of three hard-coded URLs that are decrypted at runtime. Wali will try to reach all three URLs, one after the other, until it receives a response from the server:

After communicating with the C&C server, Wali attempts do the following:

1. Download a payload from the server using the URLDownloadToFileW API:

2. Decrypt the payload:

3. Parse the payload and execute it.

Wali can support different types of payloads from the C&C servers, including: PowerShell commands and additional plugins. Even ShadowWali was delivered by some of compromised C&C servers.

This screenshot was taken from one of subroutines in charge of parsing and executing the payloads, in this case PowerShell commands:

Analysis of Wali's C&C payloads

The Wali backdoor was observed downloading two different types of post-infection payloads:

- Reconnaissance and Credential Theft Plugin: This payload executes a series of commands to gather information on the compromised host and its network environment. In addition, it contains a Mimikatz module to dump locally stored credentials.

- xxmm malware: This is a variant of ShadowWali, which exhibits slightly different capabilities and a different persistence mechanism.

Payload one: Reconnaissance and credential theft plugin

During an investigation, Cybereason analysts noticed that Wali attempted to download the following payload after reaching one of its hard-coded URLs:

Once the payload is downloaded and decrypted in-memory, Wali writes its content to a temporary file:

Sep9808.tmp - 2CE05CD6AF79B10F9EE8CBEBAE8D439FF0F30F60

The temporary file is a binary file in 101MB size:

The file’s timestamp indicates that it was compiled in August 2016:

The downloaded payload performs a similar process injection routine as Wali, namely injecting a malicious code to a new instance of iexplore.exe (memory address 0x140000000):

The plugin executable size is considerably bigger than Wali’s payloads: 896KB as opposed to Wali’s 120KB to 140KB injected payloads.

0x140000000’s SHA-1: 1C822CB9B4AFA82099B8EF2B909204D9D8F4626D

The payload launches a series of reconnaissance commands after it’s executed:

-

- Ipconfig /all: TCP/IP configuration of all network adapters on the host.

- Netstat -ano: TCP and UDP connections, open ports and owner processes.

- Net user: Enumerating user accounts on the host.

- Systeminfo: Detailed configuration information about a computer and its operating system.

- find /i /n "[Device Install" C:\windows\inf\setupapi.dev.log: Enumerating devices that are installed on the host.

- reg query HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Enum\USB /s: Enumerating USB drives.

Reconnaissance commands found in the memory of the injected iexplore.exe

Last but not least, the injected code will execute an embedded Mimikatz binary in order to steal locally stored credentials and possibly perform lateral movement.

Payload two: Variant of ShadowWali

Our investigation led us to a compromised Japanese site where the attackers uploaded their malicious PHP code and the other xxmm payload (scommand.txt, SHA-1: 52921e7b488ee1a48ca098247a07d17ce610c235).

Similar to the previous C&C payload, the scommand.txt file also contains an encrypted payload:

Scommand.txt SHA-1: 52921e7b488ee1a48ca098247a07d17ce610c235

After Wali uses the hard-coded decryption key to decrypt the payload in memory, it writes the decrypted contents to a .tmp file in %temp% folder. Once the .tmp file is written to disk and executed, it will also create a batch file that will be used for self-deletion:

This self-deletion mechanism is consistent to both backdoors of the "xxmm" family, and is found in the code of its "loadsetup" component:

C:\Users\123\Documents\Visual Studio 2010\Projects\xxmm2\Release\loadSetup.pdb

Downloaded payload details:

File name: rr2E9E.tmp (original name: test.exe)

SHA-1: 133C7B74E35D9DCC3BD43764CB18E59C1B74190F

PDB Path: C:\Users\123\Documents\Visual Studio 2010\Projects\shadowWalker\x64\Release\BypassUacDll.pdb

rr2E9E.tmp binary’s file timestamp is from May 2016:

The resources section of the PE file contains two additional PE files:

102 (32bit payload)- 8123534DDE8AC4AF983DB302A06427AAB00EDD55

105 (64bit payload) - BC725B8FF4446A72539F5C5B0532CC0264A51D9C

ShadowWali: Another xxmm backdoor

ShadowWali is also a member of the xxmm backdoor family, written by the 123 author and can be considered Wali’s older brother. The timestamp of most of the observed backdoor sample dates back to 2015 and continues until mid-2016. Wali’s timestamps, meanwhile, run between 2016 and 2017. This could be viewed as either an older version of Wali or as a separate, older project the 123 author developed.

Although there are many similarities between the two siblings, they are also clear differences:

- Strings Discrepancy: The indicative "Wali" string is not found on any of the samples we identified as ShadowWali. In fact, the binaries of ShadowWali contains many strings that do not appear in Wali backdoor. At the same time, some of the strings that appear in ShadowWali samples, show resemblance to strings usually found in Metasploit’s Meterpreter payloads:

Strings indicative of the xxmm backdoor family:

Strings indicating the usage of stdapi functions, which are also found in Metasploit's Meterpreter:

- Mostly 32-bit payloads: Most observed samples have 32-bit support, however, later samples also came with 64-bit support. This could be regarded as the missing link in the evolution of Wali.

- Different RC4 key: ShadowWali a slightly shorter hard-coded RC4 key (1234) as opposed to Wali, which uses 12345.

- Different PDB paths: ShadowWali contains different PDB paths than Wali:

- C:\Users\123\Documents\Visual Studio 2010\Projects\xxmm2\Release\loadSetup.pdb

- C:\Users\123\Desktop\xxmm3\x64\Release\ReflectivLoader.pdb

- C:\Users\123\Documents\Visual Studio 2010\Projects\shadowWalker\x64\Release\BypassUacDll.pdb

- Differences in process injection:

- Some samples inject to LSASS.exe and explorer.exe instead of Internet Explorer.

- Different process injection routine, using different API calls.

- Service-based persistence mechanism, as opposed to Wali’s tendency to use the classic registry autorun.

Analysis of the process injection routine

ShadowWali uses a less common and evasive style of "process hollowing," as opposed to Wali's injection routine that uses different APIs and also combines reflective DLL injection:

| ShadowWali simplified injection routine | Wali’s simplified injection routine |

| CreateProcessA → VirtualAlloc → GetThreadContext → VirtualAllocEx → WriteProcessMemory → SetThreadContext → ResumeThread | CreateProcessA → OpenProcess→ VirtualAllocEx→ WriteProcessMemory→ GetVersionEx → CreateRemoteThread / NtCreateThreadEx |

Example of the last stage of ShadowWali’s process injection, showing SetThreadContext/ResumeThread APIs which are used in that style of "evasive process hollowing:"

Variation in injected host processes

As opposed to Wali’s tendency of injecting to iexplore.exe, ShadowWali seems to exhibit more variation, and we observed it injecting code to explorer.exe and LSASS.exe, as can be seen in the following example:

File Name: SMSvcHost.exe, SHA-1: 168524E2292E376B2036C41E691A434BAC3A89E

Additional persistence mechanism

In addition to the previously documented persistence mechanism using the classic registry autorun (currentversion\run), some samples showed a different persistence mechanism that is based on Windows Service as autorun, as can be seen below:

File: C:\Program Files\Common Files\System\reginie.exe

SHA-1: 7DDEDADB81EE7A00F07F40686F078A7974E0C2D1

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\services\swprv7

C&C payloads - Image file Steganography

While analyzing the C&C communication of ShadowWali, it was noticed that some of the compromised sites served image files with hidden code inside them:

hxxp://[REDACTED].co.jp/magento/media/css/css.php

The image files all had one thing in common; at the end of the file, there was an appended section containing the encrypted payload. The section begins with “###RRRR” and ends with “ZZZZ###:"

When the image is downloaded, ShadowWali will search for those start-end markers , and once found, it will decrypt the payload between them. The decrypted payload results in a new URL, leading to another domain:

hxxp://[REDACTED]/data/plugin/upgrade.php?t0=000052ef&t1=0&t2=bb9c8e4d&t3=0

This is consistent with the built-in “changeURL” functionality found in the sample’s binary:

The xxmm builder dissected

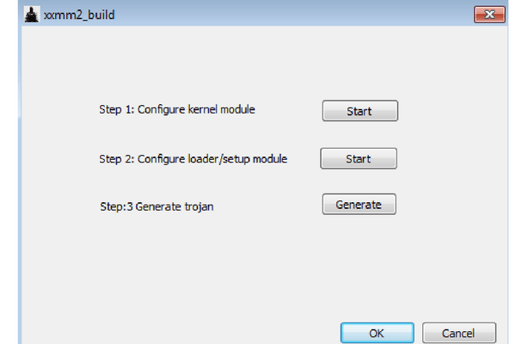

Cybereason managed to obtain a copy of the xxmm builder, the tool with which the malware author "123" generated the xxmm family backdoors:

File Name: xxmm2_build.exe

SHA-1: E5f5d64bf49b10dd4591907f34357be6cecf55b7

Fun fact: The icon of the “xxmm builder” was taken from “Batman: The Dark Knight Rises.”

The builder is written in C++ and was compiled in January 2015, which is consistent with the appearance of ShadowWali and the timestamps found in the samples’ executables.

The builder is part of the xxmm2 project and was also generated on user 123's machine, as indicated in the PDB path:

As seen in the builder’s main menu dialog, the builder consists of three steps to generate the backdoors:

Step 1: Configure kernel module

Although the word "kernel" suggests rootkit capabilities, the xxmm backdoor family operates in user-mode and was not observed implementing kernel-related rootkit capabilities.

This step is mainly used for:

- Setting up encryption keys

- Configuring C2 communication

- Steganography-based (payloads hiding in image files)

- PHP tunnel

This explains the previous observations of steganography using “.jpg” images. In addition, it clarifies another observation Cybereason made regarding the compromised websites which are written in PHP. Looking at the PHP Tunnel feature, this makes perfect sense:

Step 2: Configure loader/setup module

This step handles the following components of the malware:

- Loader (mainly the injection routine)

- Persistence either by service or registry run key

- Configuring host process for injection. Notice the default value is iexplore.exe, which is consistent with most of the observed “xxmm” backdoors.

Step 3: Generate trojan

The final step in the trojan generation handles configuration of both 32-bit and 64-bit payloads, as well as the auto-deletion code (loadSetup).

Connection to the ShadowWalker Rootkit

The name “ShadowWalker1.0” appears at the third step of the builder, and populates the “Destination File Path” field. The same name is found in the PDB path of some of ShadowWali's samples. For example:

rr2E9E.tmp - 133C7B74E35D9DCC3BD43764CB18E59C1B74190F

The ShadowWalker1.0 rootkit was a proof-of-concept rootkit introduced by Sparks and Butler at Black Hat Japan in 2005. The code is now open source and can be found on Github. ShadowWalker1.0's rootkit functionality was not observed in any of the xxmm family backdoors.

It is not completely clear why the xxmm builder references the ShadowWalker rootkit. However, the builder's menu clearly indicates that it can support rootkit modules (probably optional). These indications are found in step 1 and 2 of the builder, with indicative names such as: "kernel module" and "Kernel template".

Conclusion

The xxmm backdoor family has been attacking Japanese targets since 2015. The backdoor family consists of two main backdoors and additional post-infection plugins used for reconnaissance, credential dumping and possibly lateral movement. In this research, we have presented the similarities and differences between Wali and ShadowWali and proven that they have one father, the 123 author. Whether it’s a case of two different backdoors or an evolution of one malware over two years is a matter of interpretation. To date, Wali and ShadowWali are still actively targeting Japanese organizations.

The identity of the 123 author remains unknown. However, there are indications that suggest that the threat actor behind Wali resides in Asia. From profiling perspective, the evidence show that the 123 author has a penchant for adapting and customizing previously introduced techniques and tools, such as the reflective loader, Metasploit modules and even the builder itself could be adapted from other builders.

Compared to other modern backdoors, the xxmm backdoor family doesn’t stand out or seem very sophisticated. However, the backdoors are proven to be effective as they successfully infected dozens of endpoints over two years, while evading traditional security products. The backdoors’ strongest feature is the inflated file sizes that can reach 200MB. The motivation behind the inflated files probably stems from the author's perception that certain security solutions might not inspect large files, which will then allow the inflated files to evade detection.

IOCs

Wali payloads:

381a99c6abe218863f352a76941c9d3a4369740a

878B77556EC3C3572D09F84CC2D8F60CD92F7D00

D044B40D4121689A1AED655DA243D2917B866B6F

A0F8CFDDB34CF44A5588903AF73F5152AF84C47E

4F5748FCE8643B95DC15511816CD8045D0A470CC

2CDE37F62202E4A0B3E6B600293563716E099413

2E340AD74FB71D86787D2801055029C8C0E0DF5B

9CC5BA99B05A0B26F04EE5F6A3EC4088B06C6B17

802722295013D866855BDED0853D6AABC3A93A6F

29bcc33d2b5b6ea192d1b87ab480f10d83406387

ShadowWali (xxmm):

C4E0035E6BB3C4A42DD593CB578D9563A2E4D0C7

13F00E24157AF0F23558F400FACBB015606C4E38

3A5975BE9B3E9B1909D0F8EFB6ADD0FFE84ADB76

168524E2292E376B2036C41E691A434BAC3A89E1

367C85179A30B20DB2163CDB0CEA6D17DD164C4A

133C7B74E35D9DCC3BD43764CB18E59C1B74190F

xxmm builder:

E5f5d64bf49b10dd4591907f34357be6cecf55b7

C&C payloads:

2CE05CD6AF79B10F9EE8CBEBAE8D439FF0F30F60

1C822CB9B4AFA82099B8EF2B909204D9D8F4626D

52921e7b488ee1a48ca098247a07d17ce610c235

File names:

Srvhost.exe

Oledb32.exe

RavRtlUpd.exe

SMSvcHost.exe

Spmapi.exe

*Domains and IPs will be discussed in part two of the blog.