This Threat Analysis Report will delve into compromised YouTube accounts being used as a vector for the spread of malware. It will outline how this attack vector is exploited for low-burn, low-cost campaigns, highlighting strategies used by threat actors and how defenders can detect and prevent these attacks.

KEY POINTS

- Exploited YouTube Accounts: Cybereason has observed threat actors exploiting older YouTube accounts to host links to malware (including infostealers like Redline and Racoonstealer and other commodity malware like SmokeLoader) that masquerade as cracked versions of popular paid software.

- Low-cost, Slow-burn Campaigns: Threat actors using these accounts make use of light-weight, modular architectures and commodity malware to run months-long attack campaigns that require little effort or investment while maintaining the capability to evade detection.

- Luring Techniques: Threat actors use a variety of techniques to lure in potential victims, including Search Engine Optimization (SEO) poisoning in languages used in the geographic regions they are targeting.

- TropiCracked: Cybereason has identified a specific threat actor, dubbed TropiCracked, exploiting this attack vector to target victims primarily in South America.

INTRODUCTION

Threat actors are constantly looking for vectors they can exploit to reach vulnerable victim assets. This can be done in a variety of ways, from the highly technical (and possibly expensive) exploitation of zero-day vulnerabilities to the shotgun approach of a phishing campaign and everything in between.

One tried and true method is the blending of social engineering with commodity malware on sites and resources commonly accessed by users across the Internet, with social media sites being a prime target for this kind of exploitation. This strategy allows attackers to leverage the high-traffic, anonymous nature of these sites, the fallibility of the end user, and the low-entry bar of commodity malware deployment to quickly and cheaply create an attack campaign capable of reaching a large audience.

While these infections are often considered trivial when compared to flashier, hands-on-keyboard attacks, the effect they can have is anything but. A user attempting to save a few dollars by googling “free software” can open themselves and their organizations to real harm.

Earlier this year, researchers at CloudSEK reported on the use of AI-generated videos uploaded to YouTube offering cracked software that was in reality malware. While the use of AI-generated videos appears to have petered off, this attack vector remains viable and is still actively exploited by threat actors.

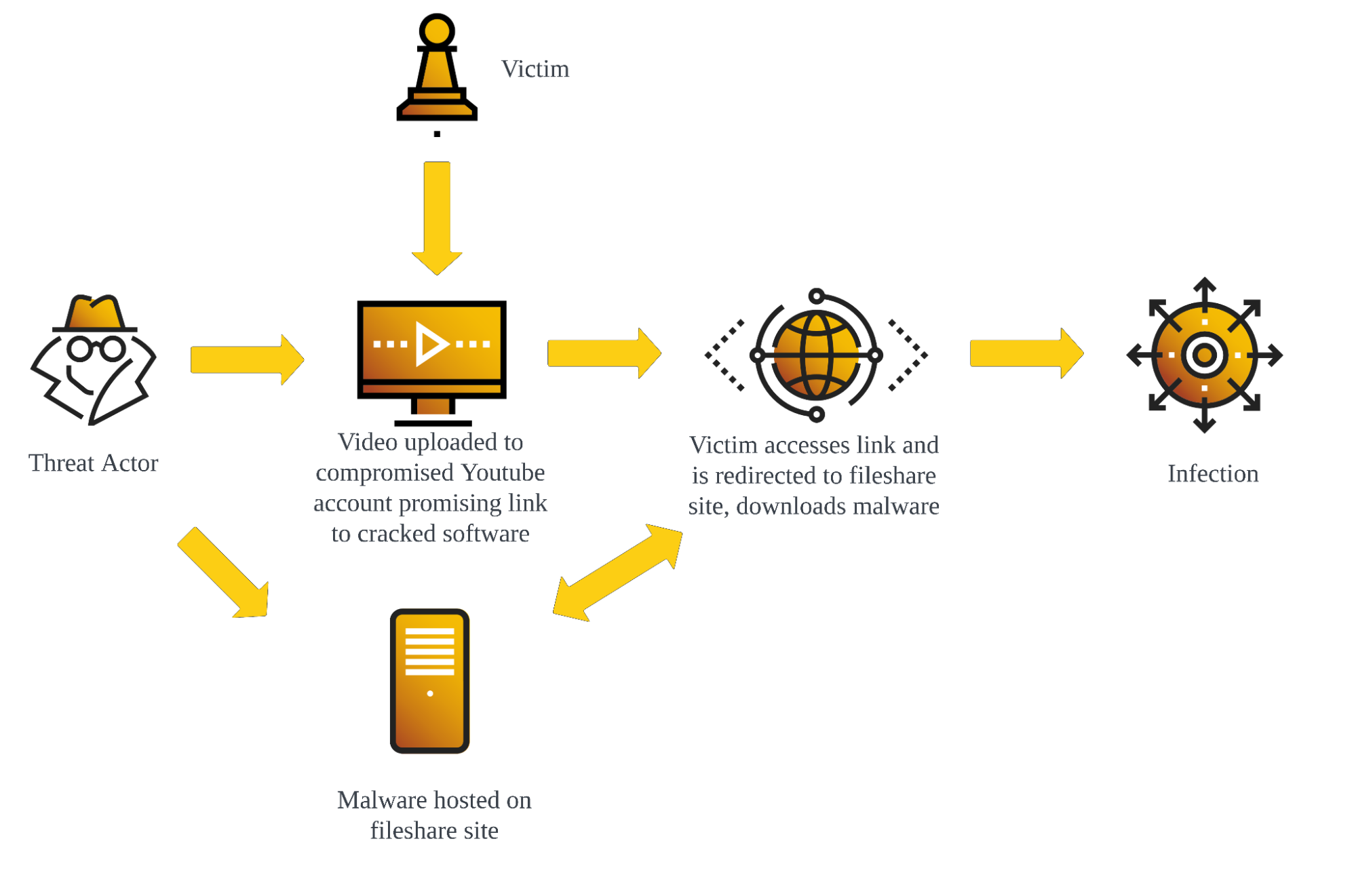

In this report, we will go over the general flow of infection based on YouTube videos, from initial account exploitation to the Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) used by threat actors leveraging this attack vector. We will then look at the actions of a specific threat actor that has predominantly used this attack vector in a low-cost, months-long campaign. For the purposes of this research we will focus mainly on the exploitation of YouTube accounts, but it is important to note that the strategies underlined here can be used on other social media sites as well.

General Infection Flow

ANALYSIS: Youtube as an infection vector

The attacker first gains control of a series of YouTube channels. They are usually several years old and have not had any uploads for several years, suggesting that old credentials leaked in data breaches may have been used to access accounts that have otherwise been abandoned but left active.

Once the attacker has control of an account, they upload a short video. This video will invariably differ from content previously uploaded to the channel, and is typically uniform in style across accounts compromised by a given threat actor, luring in victims with promises of access to cracked versions of popular paid software.

Example Of Uniform Uploads Across Channels

Example Of Similar Uploads Across Channels

Example Of Similar Uploads Across Channels

For example, one account was observed mainly uploading content related to rap music with the last upload in 2021. Then, in August 2023 a video offering a cracked version of Adobe Animate was uploaded to the channel.

Adobe Animate Crack

We can note the similar layout of the video thumbnails and titles above.

These videos are sometimes AI-generated, using voice-to-text software on top of a person speaking to camera in order to mimic human speech, but the majority of recent videos consist of text superimposed upon background animations.

Accounts vary in audience size from having no subscribers to having well over one hundred thousand. The example below shows just such a compromised account. These accounts may be particularly valuable to threat actors as they are already trusted sources for a large audience and thus more likely to lead to successful infections.

Compromised Account With Large Following

Threat actors will use various techniques to increase the chances that their videos will attract and ensnare victims. Search Engine Optimization (SEO) poisoning has been observed, where a large number of tags related to searches for the cracked software are added to a video in an attempt to lure victims using similar queries in search engines such as Google. These tags have been observed to have references in languages used in geolocations the threat actor is attempting to exploit, suggesting a regionality to attack campaigns. Note the mentions of Bangla (referring to Bangladesh) and the Spanish and Indonesian entries in the tag list below:

Tags Used For SEO Poisoning

Threat actors have also been observed leveraging the comment section of their videos, either by using other compromised accounts to create a string of positive comments to increase the perceived trustworthiness of the promised cracked software to potential victims or by locking them entirely, thus preventing already infected victims from warning others about the danger.

Below we see a comment section populated by accounts that are all several years old and highly suspected of being compromised by the threat actor, with a possible organic comment mixed in. While the bundling of cracked software with malware is a known tactic, it is important to note that in cases studied for this research the final payload did not contain the promised software but led directly to malware downloads, providing further evidence that the positive comments below were created by the threat actor.

Compromised Account Comments

The uploaded video guides viewers to its description, which contains a link to the allegedly cracked software’s download page and an access password. Attackers often use link shortening services like Rebrandly or Bitly to create these links, making them appear less suspicious. The malicious payload is typically hosted on file-sharing platforms, but in some cases compromised websites are used. Upon download, the victim can open the file using the password provided in the video description, believing it to be a legitimate software installer. However, running the file leads to infection.

Types of Malware Observed - Infostealers

While threat actors have a variety of strategies to tempt a user into downloading their payloads, the payloads themselves have been observed to consist primarily of commodity loaders and infostealers. These kinds of malware are relatively cheap and easily accessible to threat actors while giving them access to an impressive amount of functionality.

Redline

The most common malware observed during our research was Redline. Redline is primarily an infostealer that targets browser data and credentials saved on infected machines, but it can also be used as a downloader and a backdoor.

Despite the large amount of functionality a threat actor is given access to through the use of Redline, the malware itself costs about 150 dollars as a standalone binary, or 100 dollars a month as a curated subscription from the developer, also known as a Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) offering.

RaccoonStealer

RaccoonStealer was also observed linked to by several exploited accounts. Like Redline, this infostealer is fairly cheap (around 75 dollars a week or 200 dollars a month as a MaaS offering) and can be used to steal credentials and other data stored on the machine.

Other Malware

This vector is also an ideal way to spread other infostealers and loaders such as Vidar, Smokeloader, Privateloader, etc, which have all been observed in past masquerading campaigns related to cracked software.

TropiCracked

Now that we have an understanding of the basic TTPs associated with the exploitation of this attack vector, let’s look at an example in the wild. In this section we will be following the actions of a threat actor Cybereason Security Services has dubbed TropiCracked. Data from Google dorks indicates that TropiCracked has likely compromised over 800 YouTube accounts in South America beginning as early as June 2022, with consistent TTPs implying the effectiveness of their initial access vector, as no significant strategy changes have been observed.

To begin, we select a YouTube video that promises access to a cracked version of Microsoft Office.

Upload Thumbnail

The account that uploaded the video is several years old and primarily hosts music-related content. The last upload of that nature was over a year ago, but a video promising a Microsoft Office crack was posted just 13 days prior.

Most Recent Uploads From Exploited Channel

The video instructs us to look at the description to access the cracked software, which provides us with a Rebrandly link marked “DOWNLOAD LINK” and password.

Video Description For Download Link

Interestingly, the Rebrandly link does not take us directly to the fileshare website, but instead to a Telegraph URL that prompts us to click the associated link to reach the file share. This type of redirection may be used to keep the actual download link from being exposed by security measures that access URLs and check them for malicious indicators. Telegraph, a blogging platform created by Telegram in 2016, allows users to anonymously publish pages without account registry, making it an ideal tool for this purpose.

Telegraph Link Redirection To Download

In this case, the Telegraph link contains the timestamp November 24, 2022, indicating at least how long this actor has been active. Additionally it gives us the password previously observed in the YouTube video description. Accessing the link takes us to a download page, which happens to be hosted on the popular file sharing platform MediaFire.

Mediafire Download Link

The file itself is a .rar archive named Setup (PA$S 5577).rar, which once again reminds us of the password necessary to decompress the archive. Downloading the archive and decompressing it leaves us with the file Setup.exe.

Setup.exe File And Properties

The file properties contain a spoofed description claiming that Setup.exe is a legitimate Makedisk product, but analysis will confirm that it is malicious.

Payload Analysis

Metadata analysis of the file confirms that it is a .NET binary packed using the Smart Assembly .NET obfuscator.

Setup.exe File Information On Detect It Easy

Due to the nature of the packing, performing further static analysis requires the use of tools such as the .NET deobfuscation/unpacking tool de4dot and the decompiler dnSpy. However, we can see that the compile date of the binary is 30 August 2023, which corresponds with the binary’s upload date on Mediafire.

Investigation into the file hash via VirusTotal shows that the binary is flagged as Redline.

Executing Setup.exe results in the following error message:

Error Message From Setup.exe Execution

However, Setup.exe does execute, spawning the Visual Basic Command Line Compiler process vbc.exe. It then exits, leaving vbc.exe running on the system.

Process vbc.exe Running After Setup.exe Terminates

Looking into the running vbc.exe process confirms attempted connections to the C2 address 95[.]217[.]14[.]200.

C2 Server Information

This is a Finland-based IP address, and itself is flagged as a suspected Redline C2 server. As vbc.exe runs, we observe periodic connection attempts to this IP address.

Attempted Connection To C2 Server

On a host with Cybereason EDR, this infection flow triggers a Malicious Operation (MalOp), which can be observed in the Cybereason Attack Tree.

Infection Attack Tree

A successful Redline infection would see credentials and sensitive information stored on the infected machine being exfiltrated to the threat actor while also possibly giving them the ability to download further payloads, access the infected machine, and continue reconnaissance activities.

The impact is an initial foothold in an affected organization's network from which further exploitation (including lateral movement around the environment) becomes possible.

Maintaining and Expanding the Attack Surface

The TropiCracked Infrastructure

Using indicators observed in the above attack as investigation parameters, we can see that TropiCracked has made economic use of a relatively small and cheap infrastructure to reach a large number of potential victims. While a fee would need to be paid to credential brokers for access to the compromised YouTube account credentials and to gain access to Redline, the use of YouTube, Telegraph, and Mediafire would all be free of cost and require little technical skill while giving the threat actor access to a wide audience.

TropiCracked appears to have made effective use of this architecture. As previously mentioned, Google dorking suggests that more than 800 accounts have been used by the threat actor to host malicious videos.

Sampling Of Additional Malicious Account Uploads

Note that each upload is for a different popular paid software. In this way the threat actor is able to lure in victims looking for a variety of software, maximizing the visibility of their uploads to reach as many potential victims as possible.

Analysis of the compromised accounts and their uploads suggests that TropiCracked is acting primarily against Spanish and Portuguese speaking targets in South America, while also leaving uploads in other languages such as English and Korean to keep the possibility of infecting global victims open. Uploads to VirusTotal of the binary and other binaries that reach out to the same C2 address are also primarily observed from South American sources.

Further, while each of these URLs contains a unique randomly-generated path they all link to the same Telegraph page, showing that the attacker has taken full advantage of Rebrandly to obfuscate their actions from both YouTube and end users alike.

Binary Swap

Due to the lightweight architecture TropiCracked uses to exploit this attack vector, they can quickly change the final payload once it has been picked up by open-source intelligence (OSINT) to bypass detection. Their main advantage in this regard is the Telegraph link they have placed between the YouTube video and the Mediafire download page.

Under normal circumstances, in order to change binaries to a payload that has yet to be detected the attacker would need to create a new Mediafire download page that hosts the updated binary. A new Mediafire download link would then be created to house the new payload.

If TropiCracked had included the direct link to the download page in each exploited YouTube upload, all of their previous download links would no longer point to their most up-to-date payload. However, as all exploited uploads link to Telegraph instead of Mediafire, the attacker simply needs to update the link pasted to their Telegraph page and all of their previous videos still point at the most up-to-date payload.

We saw this in action during research. Recall the upload date of Setup.exe was 30 August. Reanalyzing TropiCracked's architecture a couple of weeks later, we found a new Mediafire link in Telegraph leading to a Setup.exe that was uploaded on 14 September.

Updated Download Page

While the final payload is still named setup.exe, the downloaded binary has been changed. We can see that the compile date is the same as the upload date previously observed (14 September).

Updated setup.exe File Information On Detect It Easy

We can also see that it is attempting to masquerade as a new product. In this case, a setup file from RadioEdition instead of Makedisk.

Updated setup.exe File And Properties

Although the file’s main functionality (including the hardcoded C2 address) had not changed, the superficial changes made to the source code, of course, resulted in a new file hash. This means that with relatively little effort the attacker has been able to update the setup.exe linked to by all compromised YouTube accounts with a new Redline payload that had not yet been uploaded to VirusTotal at the time of this writing. Individual users and organizations that rely primarily on signature-based detections in their security architectures may therefore be vulnerable to this attack even if they had blocked previous payloads until their signatures are updated. The attacker can run this kind of update at will in order to keep their attack viable.

Beyond YouTube

While TropiCracked seems to use compromised YouTube accounts as their primary attack vector, further investigation reveals similar Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) on other sites as well.

The full Rebrandly links we have previously observed have been seen on video sharing services, with the attack vector maintaining the same IoCs. Here is an example from a Spanish-language music sharing site (note that the title is in Spanish but the description text contains both Spanish and French):

Rebrandly Link On Sites Outside Of YouTube

We also see the previously mentioned password in front of a partial Rebrandly link on pages hosted by sites that appear to have been exploited by threat actors. The partial link itself appears as part of a list of tags for SEO poisoning as previously observed, with many of these tags appearing in both Italian and English.

Partial Rebrandly Link Added To SEO Poisoning Tag Lists

This appears to be careless use of dictionaries to create SEO poisoning tag lists and may not be related to the attack we have observed.

Conclusion

Through the use of compromised credentials, clever redirects, and commonly available file sharing methods, threat actors have proven themselves capable of launching successful long-term campaigns via popular websites that take advantage of end users looking for free software.

During this research several videos made by threat actors were observed as flagged and taken down by YouTube within days of being uploaded, while others lasted months without being detected.

While social media sites will continue to expend resources towards mitigating the viability of this attack vector, as is so often the case, it falls to individuals and organizations to ensure that endpoints remain secure from these kinds of attacks.

Detection And Prevention

Effective defense against the kind of attack we have observed will consist of a defense-in-depth strategy built on top of user education. Cybereason suggests implementing the following:

- Educate end users about the dangers related to downloading and using cracked software, or freeware available on untrusted sources.

- Ensure that signature-based detection mechanisms are regularly updated to catch malicious binaries as early as possible.

- Implement behavior-based detection mechanisms in your organization to catch malicious executions and as early as possible.

Cybereason Defense Platform

The Cybereason Defense Platform is able to detect and prevent infections through the use of multi-layer protection that detects and blocks malware with threat intelligence, machine learning, and Next-Gen Antivirus (NGAV) capabilities:

Cybereason

Cybereason recommends the following actions in the Cybereason Defense Platform:

- Enable Application Control to block the execution of malicious files.

- Enable Anti-Ransomware in your environment’s policies, set the Anti-Ransomware mode to Prevent, and enable Shadow Copy detection to ensure maximum protection against ransomware.

- Enable Variant Payload Prevention with prevent mode on Cybereason Behavioral execution prevention.

Cybereason is dedicated to teaming with Defenders to end cyber attacks from endpoints to the enterprise to everywhere. Learn more about Cybereason XDR powered by Google Chronicle, check out our Extended Detection and Response (XDR) Toolkit, or schedule a demo today to learn how your organization can benefit from an operation-centric approach to security.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

|

IOC |

Explanation |

|

telegra[.]ph/Download-Link-11-24-17 |

Telegraph link leading to Mediafire download link (other similar links observed) |

|

telegra[.]ph/Download-07-19-11 |

Telegraph link leading to Mediafire download link (other similar links observed) |

|

cutt[.]us/cwPtJ |

Malware download link |

|

bit[.]ly/Ae-crack |

Malware download link |

|

drop-cloud[.]org/DUajUvEL/ |

Malware download link |

|

lorealis[.]vip/ha/ |

Malware download link |

|

95.217.14[.]200 |

C2 address |

|

4bd97df9a302f8b432031122a512b5c0eaac16c29d7c9fa3011ad38a7465be3e |

Setup.exe - SHA256 (Initially observed instance) |

|

0c0f10e45d6600cac802471617ede4b564429a14fb2a14c7b3e6ab6fea9bc9f6 |

Setup.exe - SHA256 (second observed instance) |

MITRE ATT&CK MAPPING

|

Tactic |

Techniques / Sub-Techniques |

|

TA0042: Resource Development |

T1650 - Acquire Access |

|

TA0042: Resource Development |

T1586.001 – Compromise Accounts: Social Media Accounts |

|

TA0042: Resource Development |

T1588.001 - Obtain Capabilities: Malware |

|

TA0042: Resource Development |

T1608.001 - Stage Capabilities: Upload Malware |

|

TA0042: Resource Development |

T1608.005 - Stage Capabilities: Link Target |

|

TA0042: Resource Development |

T1608.006 - Stage Capabilities: SEO Poisoning |

|

TA0002: Execution |

T1204.002 - User Execution: Malicious File |

|

TA0005: Defense Evasion |

T1055 – Process Injection |

|

TA0011: Command and Control |

T1071.001 – Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols |

About The Researcher

Ralph Villanueva is a Senior Security Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC team. He works hunting and combating emerging threats in the cybersecurity space. His interests include malware reverse engineering, digital forensics, and studying APTs. He earned his Masters in Network Security from Florida International University.