Co-Authors: Amit Serper and Alex Frazer

Last week we discussed why the Hacking Team leak is a game-changing event for cyber security, providing a brief overview of the tools the team used and distributed to their clients and the rather sophisticated tactics they deployed in order to sustain long-term operations. This week, we’ll be focusing on their actual attack process, from the infection workflow to their RCS agent operation, and the different infection processes that they utilized.

The first thing to examine within Hacking Team’s attack process is how the infection server operates. View this flowchart for a visual of the process.

The server first runs the visitor to the infected domain through a Mod_rewrite regular expression rule on the Apache httpd server to match the six character campaign ID to the appropriate exploit kit and payload in the predesignated ID directory /var/www/files/<campaignID>. If the campaign ID doesn’t match, the server automatically redirects the visitor to a 404 error. If it does, the script moves to step two.

In step two, the script checks the hit counter for that campaign to ensure it equals zero - meaning that no one has been infected by the campaign yet. It also reviews the expiration date of that particular campaign. From what we have seen, all of Hacking Team’s campaigns were standardized with a one week expiration date from the time of campaign creation.

If both the hit counter and expiration validate, the script then checks the user agent of the victim’s browser against the Browscap PHP library on the server to ensure it meets the campaign requirements, eg. Windows 7, Chrome build 43.0.2357.130.

One interesting function of the infection server was Hacking Team’s xp_filter.py Python script, which would check the victim’s system to determine if they were running Windows XP or not and run a non-XP-based exploit, or just serve a fake SWF file, empty.swf.

The script then “echoes” the content of the news payload into STDOUT, which is a hacky way that the script uses to send the payload through the webserver and from there to the victim. This is the base64 encoded and AES encrypted payload we referenced in our previous article, which contains the RCS agent and the team’s privilege escalation exploit. The shellcode executes the privilege escalation exploit first to gain NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM privileges, then executes the agent.exe for the RCS client. Trend Micro has an excellent write-up on the privilege escalation exploit.

As a reminder: “News” is Hacking Team’s jargon for the exploit payload, “customers” means targets, “article” refers to the browser and Windows version of the victim.

In addition to the Windows-based infection server, Hacking Team was also running an Android-based strategy, which utilized similar tactics but didn’t use the Flash exploit.

As a side note, we are rather proud that the Cybereason platform was able to immediately detect the privilege escalation exploit out-of-the-box on our first test in our lab.

The payload delivery process is actually impressively sophisticated, and while some may argue that the tools and exploits they were utilizing were not, their actual workflow was particularly creative. In addition, the sheer variety of delivery methods provide customers with a significantly amplified ability to gain access to their intended target(s).

Once the target(s) is infected, this is when the RCS agent goes to work. There were a vast array of modules the agent would load, depending on what Hacking Team’s customer requested, from recording webcam images, Skype calls or keystrokes to tracking financial transactions (including bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies) or pinpointing the target’s geographic position. Not to mention the mobile capabilities, such as sending invisible SMS messages that leveraged exploits in the phone’s SMS stack, thus executing Hacking Team’s agent on the phone that allowed the attackers to turn the microphone on, providing a live audio stream from the target’s phone. We will cover this more in a future write-up. The actual activities of the client and the information they sought are far less interesting than the varied attack strategy that Hacking Team used.

The above is, of course, only a single attack process. Hacking Team provided a variety of solutions depending on what their customer needed, including variations better suited for nation-state level attacks. One example of this was the use of a network injector, a particularly nasty tool that would be plugged into an upstream or ISP backbone. Once active, the network injector would be able to identify the target(s) based on a customer defined rule set and wait for the victim to visit a specific URL, such as YouTube.com. Then, it would automatically redirect the victim to the team’s infection server instead. This resulted in the “the page you requested is being loaded” redirect screen.

Another strategy, which could be used in conjunction with the network injector, was a tool called Melter. This allowed the customer to silently “melt” the RCS agent into the binary of other, benign software. While not new, when combined with the network injector, this allowed campaigns to target software downloads and ensure that the target(s) installed the client’s RCS agent alongside the piece of software they were intending to get.

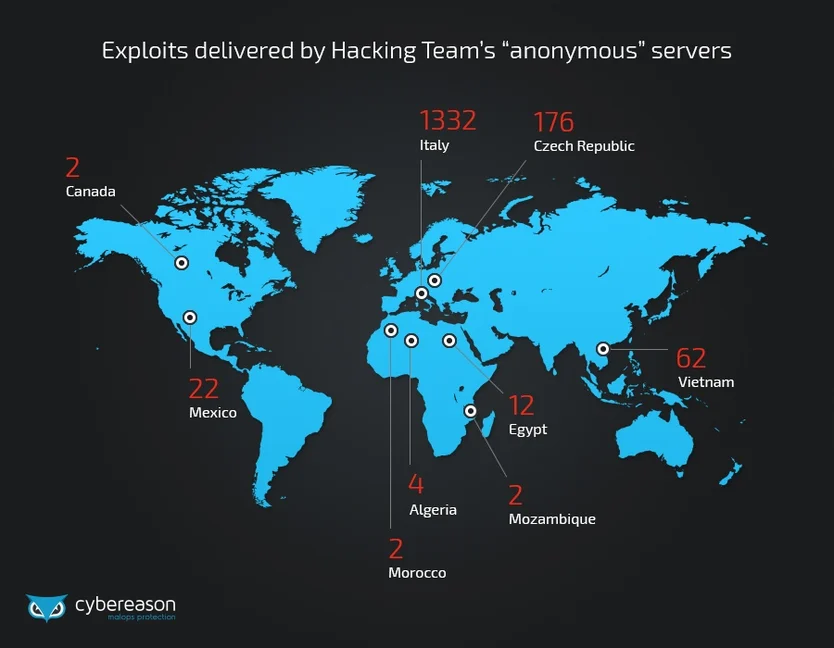

Of course, all of these strategies, on their own, are vulnerable to discovery, which is why Hacking Team also built an Anonymizer tool, which would randomize the attacker IP for each campaign in order to mask both the source and target(s) of the attack. The Anonymizer was Hacking Team’s own “private anonymization cloud” solution. This offered the ability for each customer to deploy their own virtual private servers (VPSs) that could be chained together for a anonymous proxy chain in order to eliminate tracing of the public-facing collectors run by each customer. This is accomplished by passing the victim’s collected data through several anonymizing machines to the collector node which then passed the data back to the master node (C&C server).

Below are a few examples of documentation on the Anonymizer tool, pulled directly from Hacking Team’s RCS 9.6 System Administrator Manual:

Of course, we want to stress once again that all of this source code is accessible by anyone now, so these capabilities have entered the wild, freely usable by any hackers, whether they are experts or novices. These exploitation abilities, combined with the the various reports on BGP hijacking attacks by Hacking Team (1, 2) have theoretically allowed them to make everyone on the internet pass through their systems and become infected.

Stay tuned for even more analysis from our Labs, and continued exploration of the Hacking Team leak.

You can follow Amit and Alex on Twitter at @0xAmit and @awfrazer.